Happy New Year! Here’s a little newsletter to accompany your mimosa and bagel or orange juice and bagel — whatever floats your boat.

Without further ado:

January Book Selections

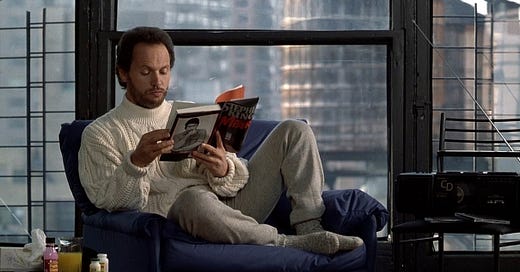

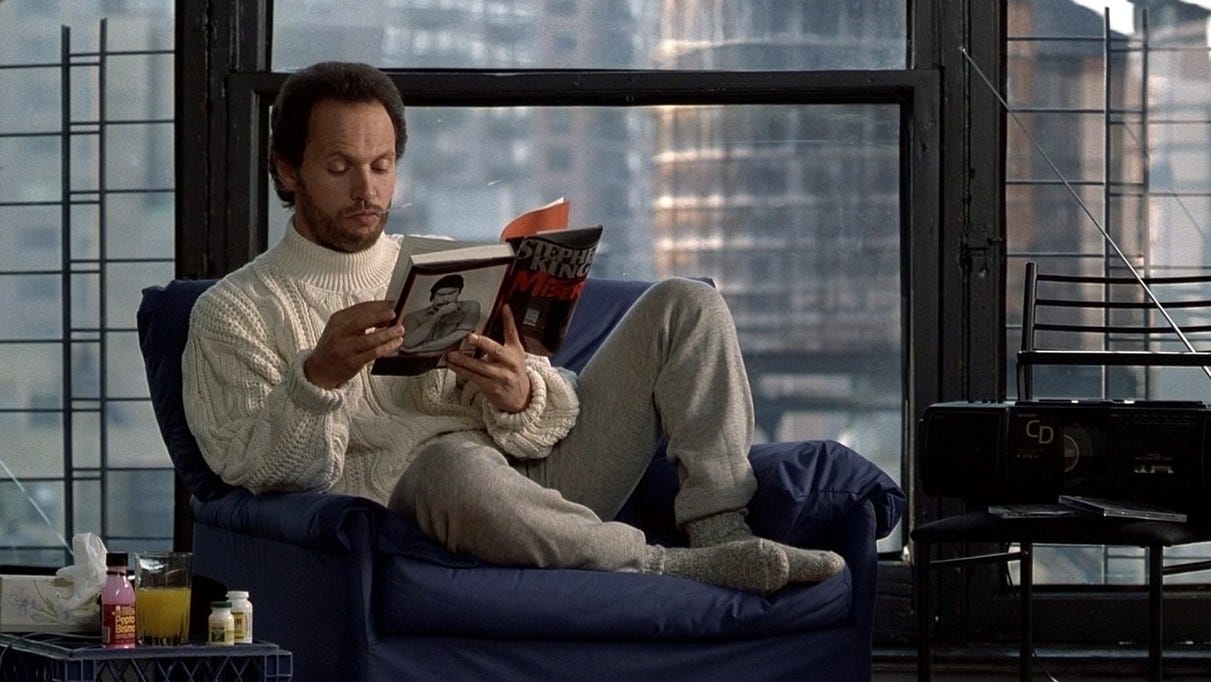

First, please take a moment to enjoy the winter king, Harry Burns, and internalize his aesthetic for the months ahead.

Okay, great.

So, we’re going to take a bit of a different approach this newsletter. Instead of me recommending five or six books that fit the ~vibe~ of the month ahead, I’m going to share my top ten favorite reads of 2023 for you to check out as we start 2024.

Keep in mind, these books aren’t necessarily the highest quality ones I read, but they are the ones I enjoyed most. Some I reviewed and won’t come as as a surprise, while others I read before launching this Substack in August.

Here we go, in order:

The Shards by Bret Easton Ellis (2023) — Duh. The vibes novel to end all vibes novels, this book has everything: teenage drama, cults, serial killers, a killer (no pun intended) early 80s soundtrack, and The Sherman Oaks Galleria. If Jacob Elordi actually gets cast as Robert Mallory in the upcoming HBO adaptation, I will never shut up about it.

Will and Testament by Vigdis Hjorth (2016) — A novel so propulsive I was waking up at 7:00 AM to read it before work. This story of inheritance and abuse skillfully embodies the experience of trauma through its elliptical form and repetitive prose. As I wrote in the November Book Review, it “operates as a chilling meditation on not only poisoned families, but also on the relationship between perpetrator and injured party, on the nebulous notion of who has the right to claim the position of victim.”

Ex-Wife by Ursula Parrott (1929) — Ex-Wife’s narrator, Patricia, walked so Carrie Bradshaw could run through Meatpacking in Manolos and Hannah Horvath could wear a yellow mesh top to a warehouse party in Bushwick. This semi-autobiographical novel captures the timeless experience of being a single girlie in New York and reads like it could have been written a month rather than a century ago.

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov (1955) — 2023 was the year I finally got over the ick factor of John Gall’s 2005 reissue cover — and the novel’s content, for that matter — and read Lolita. What a book. I found myself stunned by Nabokov’s mastery of language, his subtle use of alliteration and double entendres to create a simmering sense of unnerving sexuality (“Sitting on a high stool, a band of sunlight crossing her bare brown forearm, Lolita was served an elaborate ice-cream concoction topped with synthetic syrup. It was erected and brought to her by a pimply brute of a boy in a greasy bow-tie who eyed my fragile child in her thin cotton frock with carnal deliberation.”).

Penance by Eliza Clark (2023) — This expertly woven pastiche takes the form of a faux true crime tell-all centered on the 2016 murder of teenager Joni Wilson in the fictional British town of Crow-on-Sea at the hands of her three Tumblr-crazed classmates. Clark taps into the legacy of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (1959) to distill the cultural specificity of the mid-2010s and timeless cruelty of teen girlhood.

The Six Wives of Henry VIII by Alison Weir (1991) — The way I made this book my entire personality for the month of January. Weir uses novelistic prose to narrate Henry VIII’s six marriages in detail. She paints a compelling portrait of each woman and relationship, as well as the infamous king himself.

The Guest by Emma Cline (2023) — In her second novel, Cline distills the cultural zeitgeist of the Hamptons through the lens of an outsider. Inspired by John Cheever’s 1964 short story, “The Swimmer,” The Guest follows 23-year-old escort-turned-grifter Alex as she drifts between homes out east over the course of a stifling week in the lead-up to Labor Day. As my friend Ama (hi, Ama) put it in her LARB review: “The story reads like a summer day in August, reflecting its time, place, and setting. The tone is slow and dreamlike, and Cline uses Alex’s interiority as a device to intentionally create a loose grip on reality for the reader as Alex drifts across the island in a drug-fueled haze.”

The Summer Book by Tove Jansson (1972) — Simply put, this tender, lyrical novel — the perfect midsummer read — made me want to hug my grandma. As I described in the August Book Review: “Written by Moomins mastermind Tove Jansson in the wake of losing her mother, The Summer Book weaves a portrait of the thin line between humans and nature, life and death, through a series of 22 vignettes. Each one follows a summertime adventure undertaken by a girl named Sophia and her grandmother, both of whom reside on a remote Finnish island with Sophia’s father…Jansson crafts lyrical prose (translated from Swedish by Thomas Teal) that captures tragedy and comedy in equal measure, presenting extreme youth and old age as parallel experiences marked by supervision and play.”

Elvis and Me by Priscilla Presley (1985) — The basis of Sofia Coppola’s Priscilla, Elvis and Me, told tenderly from Priscilla’s point of view, traces the titular couple’s relationship from incept to dissolution. This celebrity memoir dispels the myth of Elvis as an untouchable god through the lens of his wife’s journey toward self actualization.

The Last Picture Show by Larry McMurtry (1966) — The basis for Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show (1971), one of my favorite movies, this semi-autobiographical novel by Larry McMurty traces the story of a small town in Texas and its inhabitants, operating more like a collection of compelling character studies than a book with a straight-through plot line. As someone who loves a “no plot, just vibes” novel, this one hit.

Honorable Mentions (in no particular order with my past reviews and overviews linked, where applicable): Brother of the More Famous Jack by Barbara Trapido (1982); Margot by Wendell Steavenson (2013); The Bad Seed by William March (1954); The Informers by Bret Easton Ellis (1994); Happening by Annie Ernaux (2001); Sweetbitter by Stephanie Danler (2016); Agatha of Little Neon by Claire Luchette (2021); The Barbizon: The Hotel that Set Women Free by Paulina Bren (2021); My Last Innocent Year by Daisy Alpert Florin (2023); Desperate Characters by Paula Fox (1970); Good Morning, Midnight by Jean Rhys (1939); Lunar Park by Bret Easton Ellis (2005); Girl, Interrupted by Susanna Kaysen (1993); The Last of Her Kind by Sigrid Nunez (2005); Memento Mori by Muriel Spark (1959); The Big Love by Mrs. Florence Aadland (1961); Love by Hanne Ørstavik (2018)

While we’re on the topic of 2023 favorites…

Top Movies of 2023

Once again, I am not using quality as a ranking tool here; I’m simply basing this list off of the films I had the best time watching, for various different reasons.

Here we go:

Rosemary’s Baby (1968, dir. Roman Polanski) — Arguably Polanski’s magnum opus (I love Chinatown (1974) too, don’t @ me). As I wrote back in October, the film “follows Rosemary Woodhouse (played by Mia Farrow) and her struggling actor husband Guy (played by John Cassavetes) as they move into the Bramford, a fictional version of the Dakota. The building has a haunted reputation riddled with stories of witchcraft and murder, as well as nosy neighbors in the form of older couple Roman and Minnie Castavet (played by Sidney Blackmer and Ruth Gordon at her very best). When she becomes pregnant shortly after their move, Rosemary’s physical condition starts to deteriorate, drawing her mental coherence into question. Every aspect of this film — from Farrow’s harrowing performance to its ‘stiflingly chic interiors’ — work together to draw the audience into the quiet terror of its world.”

Shadow of a Doubt (1943, dir. Alfred Hitchcock) — Hitchock’s favorite of his films, Shadow of a Doubt holds a perfect score on Rotten Tomatoes for a reason. A master class in suspense from the Master of Suspense, this noir centers on “an average American family,” bored with the doldrums of daily small town existence until their relative, Uncle Charlie (played by my king, Joseph Cotten), comes to visit.

American Gigolo (1980, dir. Paul Schrader) — Bret Easton Ellis’s Roman Empire, American Gigolo follows Julian Kay (played by Richard Gere), a male escort who makes a lucrative living from his relationships with older women across Los Angeles. He lives a carefree, luxury existence — until one of his clients gets murdered. Schrader distills the texture of a specific place, a particular time — LA, the early 1980s — through the film’s costuming, soundtrack, and performances, culminating in a vibe best captured in the iconic opening shot of Julian cruising down PCH while “Call Me” by Blondie blares in the background.

Dick (1999, dir. Andrew Fleming) — This Watergate comedy, which hit theaters prior to Mark Felt’s 2005 Vanity Fair interview, in which he came forward as the mysterious figure behind Nixon’s downfall, poses the question: what if two teenage girls were Deep Throat? Dan Hedaya, aka: Cher’s dad from Clueless, plays Nixon, and the film ends with Michelle Williams and Kirsten Dunst rollerblading around the Oval Office to “Dancing Queen” by ABBA. Five stars, no notes.

Gaslight (1944, dir. George Cukor) — Hunter Harris said it best in her October movie round-up: “Ingrid Bergman ate down in this movie. Y’all are not touching her in Gaslight — what a visceral performance of a woman weighed down by anxiety and delusion, love, and grief.” SO true. As I put it in yesterday’s December Movie Review, this psychological thriller “delivers an all gas, no breaks (no pun intended) plot in tandem with careful characterization brought to life by an incredible cast of actors,” including Bergman, Charles Boyer, and Joseph Cotten, as well as Angela Lansbury in her film debut.

The Shining (1980, dir. Stanley Kubrick) — As you probably well know, this horror masterpiece follows Jack Torrance (played by Jack Nicholson) as he takes on the role of winter caretaker at an old Colorado hotel, The Overlook. His sanity famously starts to slip as time wears on, putting his wife, Wendy (played by Shelley Duvall) and son, Danny (played by Danny Lloyd) in danger. From my perspective, this film, at its core, addresses the reality of domestic terror through the lens of horror, with Duvall giving a stunning performance (that, as I see it, Kubrick and Stephen King unfairly criticized).

Frances Ha (2012, dir. Noah Baumbach) — The second collaboration from Greta Gerwig and Noah Baubach, Frances Ha traces the trials and tribulations of 27-year-old dancer Frances Halladay (played by Gerwig). Shot in black and white, this coming-of-age film shows Frances navigating the dual evolutions of her friendships and career, capturing the quintessence of what it means to feel lost in your late twenties.

The Seven-Year Itch (1955, dir. Billy Wilder) — This summer in the city rom com centers on publishing executive Richard Sherman (played by Tom Ewell), whose wife and son have departed to Maine on holiday, leaving him alone in their New York City apartment. He vows to stay celibate until temptation arrives in the form of a new neighbor, an unnamed model and actress (played by Marilyn Monroe). As I put it in my review back in August: “Some may debate Some Like It Hot versus Gentlemen Prefer Blondes as Monroe’s magnum opus, but I’d make the case for The Seven Year Itch.” Her comedic timing and physicality carry the film, “giv[ing] life to a situation most women I know have faced at one point or another; what Richard views as enticement is simply her character moving through life.”

The Lost Weekend (1945, dir. Billy Wilder) — Film Forum’s Billy Wilder Festival back in July was apparently a big one for me this year. The Lost Weekend traces a 48 hours in the life of Don Birnam (played by Ray Milland), concurrently fracturing into a non-linear narrative that paints a fulsome portrait of addiction’s individual and collective impact. With stunning black and white cinematography, this harrowing tale of alcoholism captures a bygone version of New York, a time when people considered going out in Midtown chic.

Priscilla (2023, dir. Sofia Coppola) — In her latest film, Sofia Coppola brings Priscilla Presley’s 1985 memoir, Elvis and Me (discussed above), to life. Priscilla honors its titular character’s perspective and, per the November Movie Review, “captures and cultivates the aesthetic of youthful powerlessness and exquisite loneliness,” the thin line between girlhood and womanhood.

Honorable Mentions (in no particular order; once again, with my past reviews linked, where applicable): Touch of Evil (1958), Boogie Nights (1997), Girlfriends (1978), The Stepford Wives (1975), In a Lonely Place (1950), Barbie (2023), Lost in Translation (2003), The Last Days of Disco (1998), Rebel Without a Cause (1955), 32 Sounds (2022), Contempt (1963), Thelma and Louise (1991), Purple Noon (1960), Saltburn (2023), Days of Heaven (1978), The Third Man (1949), Selves and Others: A Portrait of Edward Said (2003)

Upcoming Content to Consume

IFC Center: Casablanca (1942) (Dates: 1.1-1.4) — Kick off the year with the return of Casablanca at IFC! I love this film, arguably a perfect one, from the story to the soundtrack to phenomenal performances from Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman, and Claude Rains.

My hottest of hot takes though is that I prefer To Have and Have Not (1944), simply because the chemistry between Bogart has with Lauren Bacall blows the believability of his romance with Bergman out of the water, but turn it into a double feature and assess for yourself. (To Have and Have Not is available to rent on Amazon Prime Video for $2.89!)

Film Forum: The Third Man (1949) in 35mm (Dates: 1.1-1.4) — As I put it in yesterday’s December Movie Review, “if there’s one thing I’ve learned over the past year, it’s that you can’t go wrong with a Joseph Cotten movie.” I’ve had the pleasure of seeing Cotten play three very different parts in this film, Shadow of a Doubt (1943), and Gaslight (1944), and he slays every time.

Directed by Carol Reed, The Third Man stars Joseph Cotten as pulp Western writer Holly Martins and Orson Welles as his old friend, Harry Lime. Per Film Forum, Holly arrives in Vienna to meet up with Harry, “only to find that he’s dead — or is he?” This twisty noir, an exploration of morality and corruption set against the backdrop of “rubble-strewn postwar Vienna,” won the Palme d’Or at the 1949 Cannes Film Festival and secured Robert Krasker the 1951 Academy Award for Best Cinematography - Black and White.

Film Forum: Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978) (Dates: 1.1-1.4) — Watching this narratively enthralling, visually stunning film feels like living inside an Edward Hopper painting for 95 minutes. Directed by Terrence Malick, Days of Heaven takes place in the Texas panhandle in 1916, where Chicago laborer Bill (played by Richard Gere); his little sister, Linda (played by Linda Manz); and his girlfriend-masquerading-as-his-other-sister-for-still-unclear-reasons, Abby (played by Brooke Adams), work the wheat fields of a wealthy farmer (played by Sam Shepard). When the farmer starts to fall for Abby — and she encourages his advances at Bill’s behest —, things get weird.

Malick and cinematographer Néstor Almendros shot the film almost exclusively during “magic hour,” drawing on the silent film practice of relying on natural light. Almendros has commented on how the approach left the crew with only 20 useful minutes per day, but translated to an arresting aesthetic on screen. Days of Heaven won the 1979 Academy Award for Best Cinematography, with Almendros cleaning up at the Cannes Film Festival as well.

Because Days of Heaven has such stunning cinematography, I highly recommend trying to catch it at Film Forum if you’re based in New York. To better grasp the scope of Malick’s thematic interests and directorial style, stream Badlands (1973), starring Sissy Spacek and Martin Sheen, either beforehand or afterward.

The Center for Fiction: Tolstoy's "Master and Man" and a Cocktail with Pam Newton (Date: 1.11) — This in-person event will include drinks and a discussion of Leo Tolstoy’s acclaimed 1895 short story, “Master and Man.” Per The Center for Fiction: “It tells the tale of a landowner and a peasant setting out on a journey by horse-and-sleigh and becoming lost in a brutal snowstorm. The power of the story lies not only in the gripping and harrowing narrative, so richly imagined by Tolstoy, but also in its spiritual exploration of basic human goodness and redemption.”

I haven’t read Tolstoy’s short fiction, but Anna Karenina (1878) — yes, famously a novel about society and fidelity, but also, like “Master and Man,” a “spiritual exploration of basic human goodness and redemption” through Kitty and Levin’s lesser advertised plot line — ranks among my favorite novels, so I’m looking forward to this upcoming event.

Registration costs $30 and includes beer, wine, coffee, or a cocktail. Attendees will receive a PDF copy of the story via email!

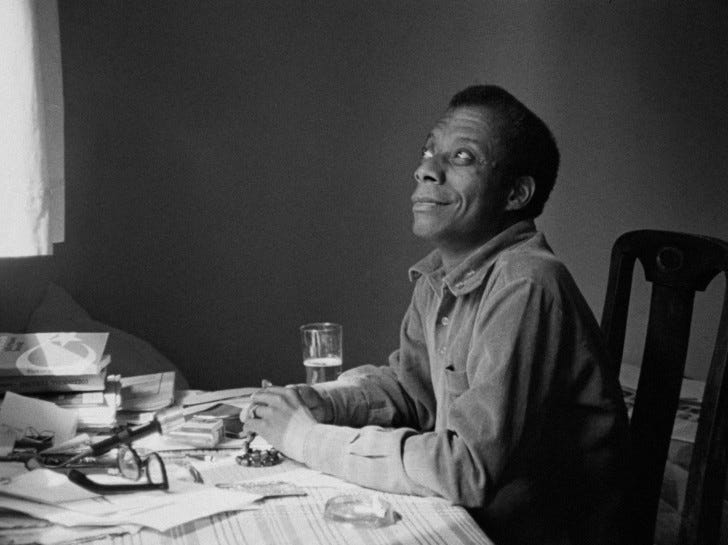

Film Forum: Baldwin Series (Dates: 1.12-1.25) — Presented in commemoration of James Baldwin’s centennial year, this upcoming series will feature a 4K restoration of I Heard It Through The Grapevine (1982). In the 90-minute film, Baldwin reflects on his experiences traveling in the South at the height of the Civil Rights Movement and, per Film at Lincoln Center, “lays bare the fiction of progress in post–Civil Rights America.”

Film Forum will also show three short films that follow Baldwin across Istanbul (1973), Paris (1971), and London (1968); Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro (2016), a documentary resurrecting Baldwin’s unfinished project exploring the Civil Rights movement and his assassinated friends, Malcom X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Medgar Evans; and James Baldwin: The Price of a Ticket (1989), what Film Forum describes as “an emotional portrait of Baldwin that uses rarely-seen archival footage, and melds intimate interviews (with writers Maya Angelou, Amiri Baraka and William Styron, among others), and public speeches, with cinéma vérité glimpses of Baldwin and scenes from his funeral in December 1987.”

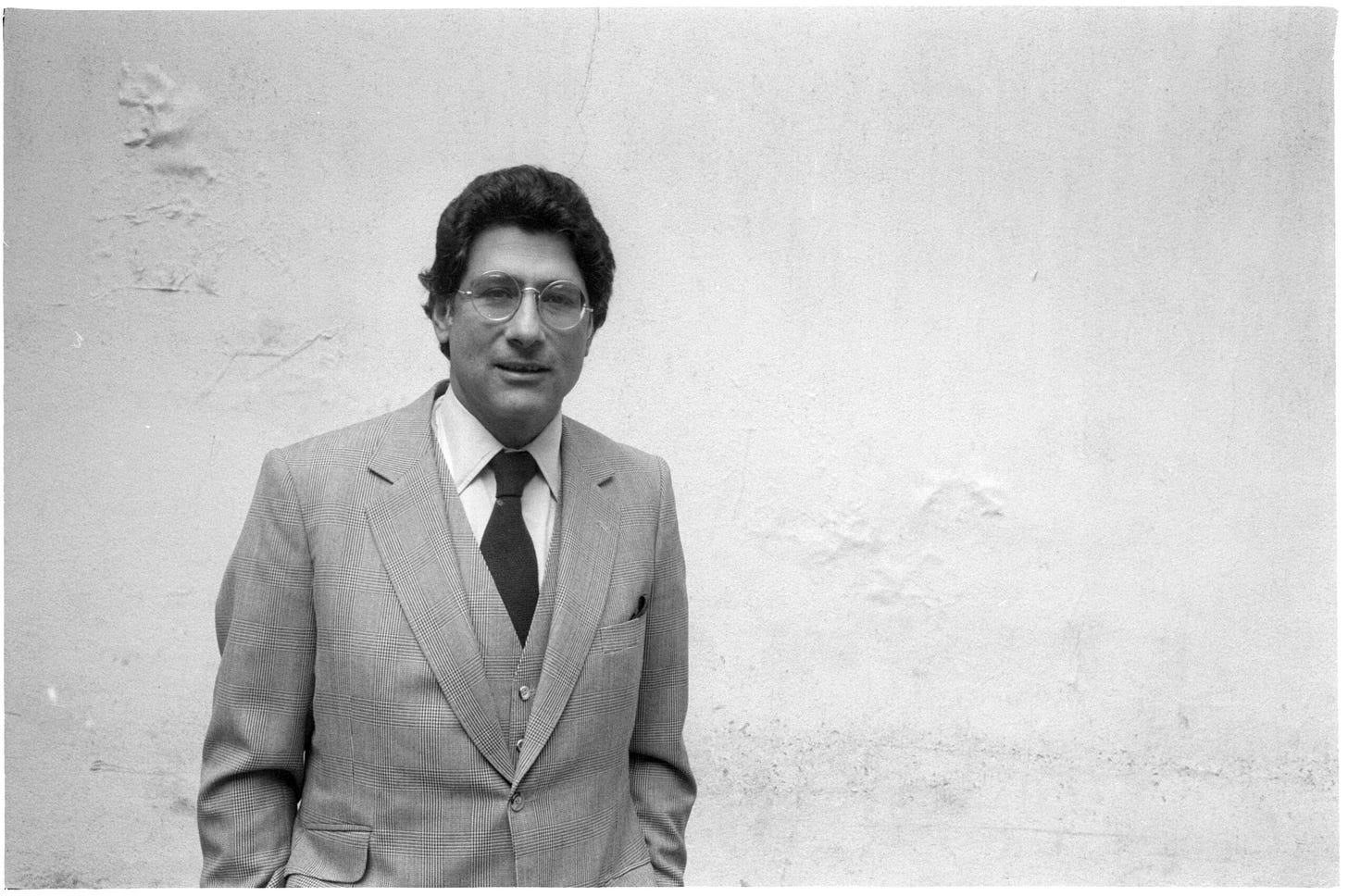

Remembering Edward Said (Date: 1.16) — In September, I had the pleasure of attending a screening of Selves and Others: A Portrait of Edward Said (2003) at Film Forum to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the Palestinian American intellectual and literary critic’s death. His widow, writer and activist Mariam Said, provided opening remarks, framing the film as Said’s reflection on his own legacy as his forthcoming death at the hands of leukemia loomed.

Now, this month, Duke University will mark the anniversary of Said’s death — and, by extension, the scope of his life — via an upcoming Zoom webinar centered on his contributions to the realm of literary criticism. The website details: “2023 mark[ed] twenty years since the death of Edward Said, a figure who has been essential to the North American history of comparative literature whether understood through its philological bias, or its forms of postcolonial critique and expansion. The John Hope Franklin Humanities Institute at Duke University and the American Comparative Literature Association plan to come together to mark Said’s influence on the humanities generally, and comparative literature in particular, through a webinar event centered on Said’s late work, Freud and the Non-European.”

You can register here if interested.

Weekly Meditations with Melissa Broder (Timing: Ongoing) — Melissa Broder — bestselling author of The Pisces (2018), Milkfed (2021), and Death Valley (2023) — recently announced plans to hold weekly meditations for writers via Zoom. If you email her at eatingaloneinmycar@gmail.com (so valid), you will receive an email each week with details on the date and time.

Miscellaneous Musings

In Defense of Girl Culture — ICYMI: The Cut ran a piece from Isabel Cristo, Associate Editor at The Atlantic, unpacking 2023 as “the year of the girl.” Cristo critiques the pop cultural phenomena that dominated the past year, from Barbiecore summer to the Eras tour to the bow craze, and makes the case that these markers reflect a so-called fear of womanhood (“The fervid enthusiasm of grown women to participate in the veneration of girlhood raises a slightly unsettling question: What is it, exactly, that’s so uninviting about being an adult woman?”). I developed a response piece over the weekend that you can check out here!

Pauline Kael on Brian De Palma’s Carrie — Quentin Tarantino recently appeared on two episodes of The Bret Easton Ellis Podcast (linked here and here) to talk about key films of the 1970s in tandem with the release of his new book, Cinema Speculation, a series of 15 essays on the subject. Over the course of the episodes, legendary American film critic Pauline Kael’s 1976 review of Carrie gets cited by both as the greatest review of all time, so, of course, I had to check it out.

For those of you unfamiliar with Kael, as The New York Times so aptly put it in 2011: “Kael is remembered not for her particular judgments or ideas, but rather for her voice, for an outsized literary personality that could be enthralling and infuriating, often both.” She had some hot takes, famously stanning Shampoo (1975) and, per The New Yorker, slamming smash hit The Sound of Music (1965) as “the single most repressive influence on artistic freedom in movies.” Kael wrote for The New Yorker from 1968 to 1991 after her film criticism book, I Lost It at the Movies, garnered mass awareness in 1965. She died in 2001.

From my perspective, Kael’s review of Carrie (1976) lives up to the hype. Every sentence has purpose — and bite to boot (“But the high-school students — each with a whopper crop of hair — bounce off the beach-party movies and Peyton Place and Splendor in the Grass and American Graffiti. The villains, the exuberant, beer-guzzling Billy (John Travolta, who might be Warren Beatty’s lowlife younger brother) and his bitchy girlfriend Chris (Nancy Allen), with her lewd dimples and puffed ringlets, have the best dialogue — their language is so stunted that every second word is profane.”). Kael acknowledges how De Palma elevates the film above your typical teen slasher, situating it in the broader context of the horror canon. She calls out meta references to Psycho (1960), almost establishing Carrie as a conceptual predecessor to Scream (1996) (“There are no characters in Carrie; there are only schlock artifacts. The performers enlarge their roles with tinny mythic echoes; each is playing a whole cluster of remembered pop figures. Sissy Spacek’s Carrie goes to Bates High — Norman Bates ran the motel in Psycho — and her gym-shower scene is a variation on the famous Psycho shower.”).

The Making of Apocalypse Now (1979) — Okay, so, I listened to approximately six hours of The Bret Easton Ellis Podcast while cleaning my apartment last week, and it’s showing. After Tarantino, Bret welcomed author Sam Wasson for a set of episodes centered on Francis Ford Coppola.

For context, Wasson’s work typically focuses on Hollywood history, with past books tackling topics ranging from the life of Bob Fosse to the making of Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974). He co-authored Hollywood: The Oral History (2022) alongside Jeanine Basinger, and his latest book, The Path to Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story, just published at the end of November.

Okay, so the year is 1977, and Francis Ford Coppola is not okay. His wife has just found out he’s carrying on two (!!) extramarital affairs (one of which is with Melissa Mathison, future wife of Harrison Ford and screenwriter of E.T. (1982)), and Apocalypse Now, his Vietnam War film based on Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novella, Heart of Darkness, has hit over 200 days of filming. His budget is maxxed out, with his long-limping production company, American Zoetrope, on the line. And yet he goes on to deliver a “work in progress” cut of the film to critical acclaim at the 1979 Cannes Film Festival, taking home the Palme d'Or. But first comes an on-set heart attack, a typhoon, and Marlon Brando being Marlon Brando.

I highly recommend digging into the history of this film’s production for a good time if you haven’t already, whether in the form of Wasson’s latest book (the best route for Coppola fanatics; the Hollywood legend heavily cooperated with interviews, speaking with candor about his successes and failures professionally and personally as Wasson prepared to write the book), the set of podcast episodes (linked here and here), or this much shorter Collider article.

Supplemental Reading

As always, don’t forget to use archive.ph if you can’t access these pieces or any of the ones throughout my Substack!

The New Yorker: Mosab Abu Toha's Perilous Journey Out of Gaza

Air Mail: Behind the Making of American Graffiti

The New Yorker: Victor Laszlo’s Blog

Town & Country: How Maestro Recreated Leonard Bernstein's Dakota Apartment

Cocktail of the Month

This January, we’re channeling warm weather vibes during the coldest of months. I first had this cocktail upstate a few summers ago, and it quickly became a favorite.

Add one and a half ounces of dark rum, one and a half ounces of pineapple juice, three quarters to an ounce (to taste) of Campari, half an ounce of lime juice, and half an ounce of either simple or maple syrup into a cocktail shaker, and fill it with ice.

Shake until cold and strain into a cocktail glass. Garnish with a pineapple wedge, pineapple leaves, or fresh mint.

That’s all for now! Keep an eye out for the December Book Review later this week!

xo,

Najet