When I think of girlhood — and leaving it behind —, the opening sequence of Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette (2006) immediately comes to mind. Arriving in France, the soon-to-be-infamous French queen clings onto Mops, her small pug adorned with a small white bow (a fictional pet created by Coppola). A French soldier soon takes Mops away, citing the dog’s Austrian origin as the reason. Here, Coppola equates Austria with girlhood, France with womanhood. But, as Coppola fans and European history enthusiasts alike know, Marie Antoinette never really abandons her girlhood; she simply translates it to a more lavish plane, and Coppola’s film makes the case that this youthful irresponsibility becomes her downfall.

ICYMI: The Cut ran a piece from Isabel Cristo, Associate Editor at The Atlantic, entitled “Woman in Retrograde” that unpacks 2023 as “the year of the girl,” presenting it as a dire reflection of the state of womanhood. She seems to fear that the culture has begun to build scores of Marie Antoinettes, women with massive spending power ordering pink bows and ballet flats with reckless abandon, cheerfully “chirping” “hi, Barbie!” while worshiping at the altar of Taylor Swift (who Cristo describes as “a woman whose protracted adolescence is fodder for a concert tour that’s on track to be the biggest in history, thanks, of course, to the spending power of other women”). Cristo writes: “The fervid enthusiasm of grown women to participate in the veneration of girlhood raises a slightly unsettling question: What is it, exactly, that’s so uninviting about being an adult woman?”

This question, to me, builds an argument on faulty scaffolding by positioning womanhood and girlhood as diametrically opposed rather than inextricably entwined. As I see it, girlhood lives within womanhood rather than operating as an alternative to it, and the past year has sent a message — albeit, one often wrapped in capitalistic motives — supporting that. The seemingly small details that shaped the color and texture of 2023, from head-to-toe hot pink outfits to the beaded bracelet phenomenon, normalized adult women embracing girlhood, or the cultural touchstones of adolescence that defined their childhoods, on a mass scale.

Billboard recently released its updated list of the top grossing films from 1977 to the present. While Greta Gerwig made history as the first woman to create a film that topped the year-end box office tally, “Star Wars is the top franchise on this recap, with six installments that have been the year’s top-grossing film.” Despite having more U.S. male than female fans as of 2019, the franchise that netted George Lucas $11 million in 1977 maintains a central place in our cultural zeitgeist year after year. Where the widespread success of Barbie gets noted as an abnormality, a moment that “made history,” Star Wars’s status as a cultural stalwart operates as an expectation; despite its male-leaning fan base — and my personal memory of every boy I knew in the late 90s running around with lightsabers —, the franchise gets marketed as mainstream rather than a remnant of “boyhood.”

Cristo describes girlhood as “a before time: before puberty, before life, and, importantly, before feminism,” begging the question of its appeal. While she presents this statement as fact, it holds two key flaws.

First, I would dispute this idea of a linear girlhood-to-womanhood pipeline. It exists in the temporal sense, but, emotionally speaking, the experiences and touchstones of girlhood live on within women. As a result, the distinction between girlhood and womanhood blurs. In 1991, art therapist Lucia Capacchione’s book, Recovery of Your Inner Child, birthed the notion of parenting your inner child, what would become a mainstream therapeutic discourse around tending to and embracing your childlike aspects rather than turning away from them. Capacchione’s writings dispel the notion of childhood — and, by extension, for women, girlhood — as a “before,” positioning it as ever-present from a conceptual standpoint.

In a piece for Curzon on Greta Gerwig’s filmography, freelance writer Emily Maskell writes: “Across the seven features she has written or directed (or both), Gerwig has crafted stirring portraits of womanhood that interrogate coming-of-age themes and capture her heroines in times of personal evolution. Girlhood, and the progression to womanhood, are presented not as linear emotional journeys, but quests for self-discovery fueled by homesickness.” Here, Maskell frames girlhood and womanhood as co-existing concepts rather than linear poles of progression, introducing “homesickness” as fuel for self-actualization; more on that in a minute.

Second, Cristo presents girlhood as “before feminism.” She writes: “Although in reality, girlhood can be (often disturbingly) pierced by the politics of the adult world, it’s a period that precedes those choices that feminism has always concerned itself with – choices about marriage, child raising, career building, homemaking, sex, sexuality, and caretaking. It’s also a time that’s free from the consequences of those choices. In girlhood, we’re not yet even ourselves.” In contrast to Cristo, I would argue that, in girlhood, freedom from the consequences of choice actually makes us more ourselves than ever. Most girls can tune into their passions and interests, liberated from the shackles of financial autonomy and adult responsibility. As a result, girlhood has the power to serve as the conceptual zenith of feminism in how it touts the myth of limitless empowerment that adulthood inevitably dispels.

Consider Maskell’s notion of “homesickness” as fuel for self-actualization in Gerwig’s filmography; something about home, about girlhood, holds the key to the path forward, conceals a version of the heroine unencumbered by adult doubts, one she must rediscover. Girlhood marks a time when many women believe they can become anything, do anything — hence Mattel making Mermaid, Beekeeper, and President Barbie; Lizzie McGuire performing alongside an international pop star on her eighth grade class trip (??) to Rome (???); and The Powerpuff Girls redefining what it means to “fight like a girl”, repeatedly beating their archenemies in time for kindergarten recess. For Gerwig’s heroines — and women generally —, holding onto that spirit of possibility has the power to help women clarify what they want and pursue it without blinders of self doubt.

Cristo goes on: “It doesn’t help that the major touchstones of the past several years — Me Too, Donald Trump, COVID, Dobbs — are fucking miserable, and the cultural objects that accompanied them have tended to be correspondingly somber or pedantic…Instead of politics, can I interest you in some blissful, childlike ignorance?” While I agree on the fucking miserable point, equating an embrace of girlhood with “blissful, childlike ignorance” strikes me as rooted in a pre-2016 conception of women’s interests as monoliths. In fall of 2016, Teen Vogue famously re-established its role in societal discourse through its viral op-ed, “Donald Trump Is Gaslighting America.” This piece went on to become the publication’s top-read article of the year, followed by (in order): “How to Apply Glitter Nail Polish the Right Way,” “Netflix Arrivals October 2016: See the Full List,” “Mike Pence’s Record on Reproductive and LGBTQ Rights Is Seriously Concerning,” and “Dark Marks and Acne Scars: Your Complete Guide,” per The Atlantic. The multiplicity that came to define Teen Vogue’s content over the course of the Trump administration subverted traditional notions of teen girlhood, underscoring the reality that girls and women can care about the political landscape and glitter nail polish at the same time.

Despite the downfall of Sheryl Sandberg and her disciples over the course of the past three years, 2023, as I see it, put the final nail in girlboss feminism’s pop cultural coffin – at least, for now. In an interview with NPR, Hannah McCann, a lecturer at the University of Melbourne who specializes in critical femininity studies, discusses the reclamation of bimboism in tandem with Barbiecore summer. She explains: “In the 2020s, you have this change in the meaning of being a bimbo on social media where people are really working to reclaim the term ‘bimbo’ specifically…It's about not having to engage with people who are demanding that you prove yourself, or demanding that you can intellectually keep up with them or compete with them. That's why it's so jarring to patriarchal frameworks that insist you prove yourself and keep up in a way that is perfect and up to certain standards.” In short, bimboism is about being genuinely confident and unbothered, while girlboss feminism merely touted the illusion of both qualities.

From my perspective, the 2010s — culturally and aesthetically — became about blindly grasping in the direction of male power while concurrently decrying its ethics. It was an era defined by trying so hard to be a “nasty woman” and get a seat at the table that it buried childlike softness and carefree pleasure for people of all genders. Meanwhile, the past year has discarded that strained effort, a reactionary one shaped by internalized patriarchal conceptions of what gets taken seriously, in favor of a movement predicated on the notion that girlhood has no sell by date, the truth that bimboism, intelligence, and capability can and do exist simultaneously.

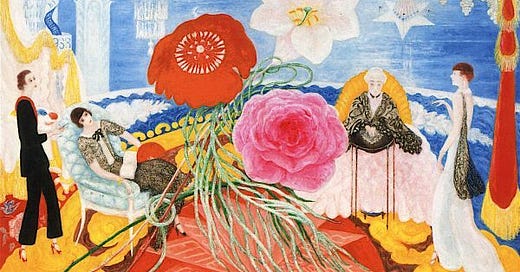

Florine!!! ❤️❤️❤️