Movies of the Month: December [2023]

New releases, two classic noirs, and Richard Gere

Happy New Year’s Eve! Before everyone heads to their plans for the night, I wanted to send through the December Movie Review.

I once again saw a handful of new releases, along with two banger noirs and a visually stunning New Hollywood classic. Also, The Muppet Christmas Carol.

Let’s get into it:

Gaslight (1944, dir. George Cukor) — Hunter Harris said it best in her October movie round-up: “Ingrid Bergman ate down in this movie. Y’all are not touching her in Gaslight — what a visceral performance of a woman weighed down by anxiety and delusion, love, and grief.” SO true.

In this psychological thriller adapted from Patrick Hamilton’s eponymous 1938 play, Paula Alquist (played by Bergman) returns to the London townhouse where she found her aunt-slash-guardian brutally murdered years earlier, joined by her new husband, Gregory Anton (played by Charles Boyer). After training to become an opera singer in Italy solo, followed by a two-week whirlwind romance, Paula hopes to make a fresh start. But soon, night after night, she begins hearing knocking in the walls, seeing the gas lighting dim throughout the house. When her experience differs from Gregory’s, Paula begins to question her grip on reality.

Without spoiling specific, Gaslight delivers an all gas, no breaks (no pun intended) plot in tandem with careful characterization brought to life by an incredible cast of actors. Beyond starring Bergman and Boyer, this noir marks Angela Lansbury’s debut as Paula and Gregory’s maid, Nancy, and features Joseph Cotten (aka: Uncle Charlie from Shadow of a Doubt) as Inspector Brian Cameron.

Speaking of Cotten, in 2005, film critic Emmanuel Levy did a deep dive on Gaslight that draws parallels to Shadow of a Doubt (1943), among other noirs. He writes: “These films use the noir visual vocabulary and share the same premise and narrative structure: The life of a rich, sheltered woman is threatened by an older, deranged man, often her husband. In all of them, the house, usually a symbol of sheltered security in Hollywood movies, becomes a trap of terror.” In discussing Shadow of a Doubt last October, I cited Roger Ebert’s reflections on how Hitchcock uses staircases “for tight little sequences of threat and escape,” to introduce “imbalance into otherwise horizontal interiors.” In Gaslight, Cukor draws on a comparable aesthetic lexicon, with the townhouse’s stairs operating as an Edwardian-era gateway to Paula’s ivory tower.

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video ($3.99)

Eileen (2023, dir. William Oldroyd) — Based on Ottessa Moshfegh’s eponymous 2014 novel — and adapted for the screen by Moshfegh and her husband, Luke Goebel —, Eileen announces itself as a descendant of the Hitchcockian noir within seconds of its start. The credits mimic the signature font that bookends Rear Window (1954), creating a visual connection between the two films — and prefiguring a narrative tie to Hitchcock’s legacy.

During the early 1960s, Eileen Dunlop (played by Thomasin McKenzie) lives an unenviable existence in her small, Massachusetts town. She works as a secretary at a boys’ juvenile detention center, harboring a sexual obsession with one of the guards, and manages her alcoholic father. Her life seems to take a glamorous turn when new psychologist Rebecca Saint John (played by Anne Hathaway) arrives at the correctional facility — until her veneer starts to crack slowly, then all at once.

Moshfegh and Goebel’s adaptation remains faithful to the novel’s characters and story while discarding elements more conducive with written prose. For instance, in the book, Eileen narrates the events of 1964 from the vantage point of 2014. The movie does away with that framing device, cultivating a more filmic sense of immediacy. It still, however, stays close to its heroine’s perspective visually and narratively. Consequently, Eilieen maintains a sense of subjectivity, drawing the truth of its title character’s perspective into question.

In a review for RogerEbert.com, Sheila O’Malley writes: “We must remember that, when we watch Eileen, directed with moody, twisty desolation by William Oldroyd, Eileen may not be the most reliable of narrators. A lifetime of being invisible and put-upon will do that to a person. Look closer at Rebecca. Her hair is more ‘nest’ than ‘style.’ She provocatively smokes a cigarette as though she's ready for her closeup, not standing in a stale-aired office surrounded by troubled teenage boys. She seems a little bit tricky. There's an edge there. But to Eileen, it's as though Marilyn Monroe herself has entered her workplace and, wonder of wonders, become her new friend, her first friend.” McKenzie and Hathaway enliven Eileen’s desperately lonely naiveté and Rebecca’s carefully constructed allure, teasing out sapphic overtones that soon turn deadly.

Where to Watch: ~a theatre near you~

The Muppet Christmas Carol (1992, dir. Brian Henson) — Yes, I just watched this movie for the first time. Yes, Michael Caine slays, as always.

Caine famously told Henson: “I'm going to play this movie like I'm working with the Royal Shakespeare Company.” And, you know what? He absolutely does.

Where to Watch: Hulu (premium subscription), Amazon Prime Video ($3.79)

Anyone But You (2023, dir. Will Gluck) — IndieWire promised me “an unapologetic, irony-free '90s-style rom-com with screwball energy and Shakespearean plotting,” and Glen Powell and Sydney Sweeney delivered.

Loosely based on Much Ado About Nothing, Anyone But You centers on Bea (played by Sweeney) and Ben (played by Powell) — named for Shakespeare’s Beatrice and Benedick, of course. After spending a memorable night together a year earlier, the pair finds themselves engaged in a war of wits at an Australian wedding weekend. But faced with both of their exes in the flesh, Bea and Ben decide to masquerade as a faux couple, and the lines between love and hate, truth and fiction, begin to blur.

I had a great time at this movie. It has an engaging plot, solid acting, and famously strong chemistry between the leads. In a review for RogerEbert.com, Marya Gates writes: “Despite the stacked supporting cast, this is really a two-hander for Powell, whose scruffy charm is reminiscent of Kurt Russell a la Overboard, and Sweeney, whose sad eyes and soft timbre recall Melanie Griffith in Working Girl.” I would add that Sweeney brings an earnestness to her performance that seems to translate the archetype of Meg Ryan’s Holy Trinity of Nora Ephron heroines to the 2020s, while also delivering well-timed physical comedy reminiscent of Mindy Kaling’s slapstick antics on the early seasons of The Mindy Project (2012-2017).

Gates goes on: “Their [Powell and Sweeney’s] palpable chemistry is enhanced through a skillful use of medium and close-up shots that bring into focus both their characters’ fire, and their shared melancholy. While the film has its fair share of wacky moments, its greatest moments are found in the many scenes where Ben and Bea truly see each other, and, eventually, find the courage it takes to embrace being with someone who recognizes the real you, flaws and all…Both are constantly talking to the people in their lives, but rarely daring to actually communicate.” As I see it, Anyone But You succeeds as a rom com for the modern age by operating within the framework of millennial and Gen Z cynicism, dissociation, and decision paralysis rather than constructing — and expecting viewers to buy into — a tangential fantasy.

Where to Watch: ~a theatre near you~

May December (2023, dir. Todd Haynes) — Okay, this one really didn’t do it for me. The three leads — Julianne Moore, Natalie Portman, and Riverdale’s Charles Melton — give stunning performances, but May December, from my perspective, felt unsure of its genre, toeing a confusing line between drama and camp.

Inspired by the Mary Kay Letourneau scandal (aka: the teacher who statutorily raped and went on to marry her sixth grade student in the late 90s) and set in 2015, May December follows actress Elizabeth Berry (played by Portman) as she arrives in Savannah, Georgia to research her role in an upcoming indie film. The subject matter? The relationship between Gracie Atherton-Yoo (played by Moore) and Joe Yoo (played by Melton), who got caught having sex in the pet store where they worked in 1992, at the ages of 36 and 13, respectively. Despite spending years in prison, Gracie now lives as a free woman; she has married Joe, with whom she has three children, and seems to have established a solid standing in their community. But, as Elizabeth’s time in Savannah wears on, the distinctions between perception and reality, delusion and truth, come into focus.

Moore and Portman meet the high bar set by their reputations, and relative newcomer Melton more than keeps up with his co-stars. His performance lives somewhere between childhood and adulthood, capturing the stunted emotional life of the character he portrays. This tension, from my perspective, manifests most prominently in a scene that shows Joe smoking weed for the first time with his teenage son, occupying the position of innocent and elder alike. In an interview with Vulture, Haynes echoes: “There’s such remarkable physicality in the choices he [Melton] made as an actor. A friend of mine saw a cut of it, and he said, ‘Charles moves like a child and an old man, a combination of the two’ — which makes so much sense given his predicament.”

While all three actors bring a natural blend of drama and humor, Marcelo Zarvos’s score layers in a jarring level of camp. His soap operatic anthem blares over scene after scene, disrupting the flow of the film rather than supplementing it. This auditory insertion cultivates an odd — and, for me, off-putting — flavor of melodrama, resulting in an uncertain sense of style, of tone; the fact that Portman’s Golden Globe nomination for Best Actress comes in the Musical or Comedy category only seems to underscore this point.

Where to Watch: ~a theatre near you~, Netflix

Days of Heaven (1978, dir. Terrence Malick) — Wow. What a thematically engaging, visually stunning film. Days of Heaven applies the sexuality and nihilism of the 1970s to a series of trials and tribulations that might crop up in a Little House on the Prairie episode, all through the prism of Andrew Wyeth aesthetics.

Set in 1916, this New Hollywood classic opens with laborer Bill (played by Richard Gere) accidentally killing his boss at a Chicago steel mill, prompting him to head for the Texas panhandle with his girlfriend, Abby (played by Brooke Adams), and little sister, Linda (played by Linda Manz). For reasons still extremely unclear to me, Bill and Abby pose as siblings rather than lovers. (Explanations I’m seeing online point to pre-marital sex as taboo at the turn of the century, but then why not simply get married? I guess because there would be no plot then. But I digress.) The trio begins working for a wealthy farmer (played by Sam Shepard) as part of a larger group, but soon stays on in isolation after Bill learns their boss has less than a year to live. He pushes Abby to capitalize on the farmer’s romantic feelings for her, with the ultimate goal of inheriting the land. When she goes along with Bill’s plan — while maintaining her relationship with him —, things start to get weird.

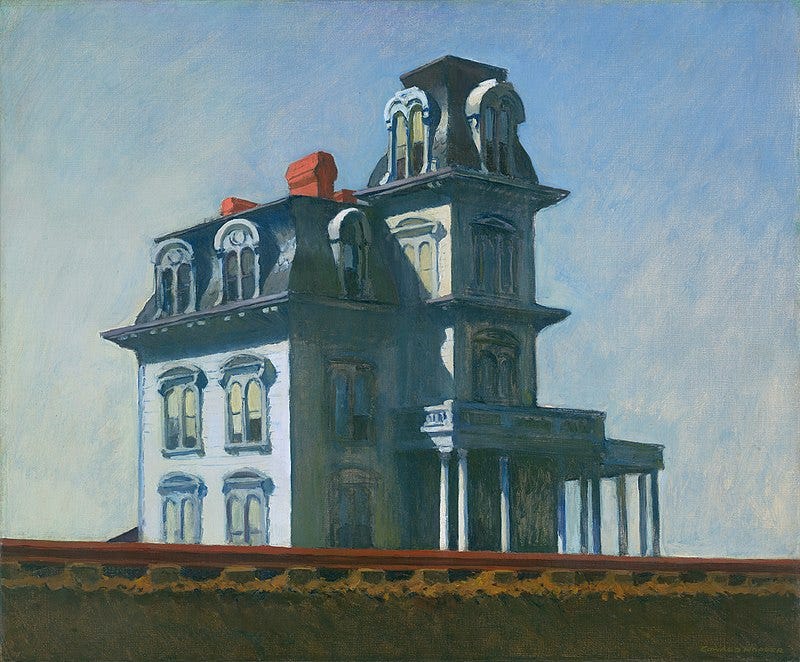

Watching Days of Heaven feels like living inside an Edward Hopper painting for 95 minutes, with the farmer’s house modeled after the American artist’s 1925 piece, House by the Railroad. Stunning images of wheat fields, winding rivers, and far-off trains distinguish its aesthetic, with several scenes shot from afar to distill the overall visual and vibe of the landscape, of the moment. Malick, for the most part, embraces silence, letting the motion of the workers, of the topography, speak for itself. The land operates in concert with the characters’ emotional arcs, serving as a visual and thematic framework alike; when Bill, Abby, and the farmer — played tenderly by Gere, Adams, and Shepard — reach their breaking points, fires blaze and locusts descend.

Malick partnered with cinematographer Néstor Almendros to capture the visual specificity of the Texas panhandle, drawing on the silent film practice of using natural lighting. The pair frequently scheduled shooting around dusk at Malick’s behest, confined to “20 useful minutes a day,” as Almendros describes in an interview with AFI Movie Club. He acknowledges that Malick’s vision “paid on the screen,” explaining: “The moment when the sun sets and after the sun sets, before it is night, the stars have light. There is no actual sun, and the light is very, very soft…that’s what we call magic hour…It’s beautiful because it’s unusual. The Impressionists knew that the most beautiful lights were the unusual lights.” The film rightfully went on to win the 1979 Academy Award for Best Cinematography.

As an aside: I recently listened to two hour-and-a-half long episodes of The Bret Easton Ellis Podcast with Quentin Tarantino (more on that tomorrow), and the pair spent several minutes discussing whether Richard Gere was too hot to pass as down-and-out laborer Bill. Despite his famously massive crush on Gere (me 🤝 Bret), Bret thought he didn’t fit the part. Meanwhile, Tarantino’s take was that he looks like a movie star, and, in the 1970s especially, you went to the movies to see movie stars. Sam Shepard definitely fits the vibe more, but I personally am never going to complain about Richard Gere appearing in a film.

I saw Days of Heaven at Film Forum, where it will continue to screen through Thursday (1.4). If you’re New York-based, run, don’t walk! Watching this especially visual film on the big screen was a special, immersive experience.

Where to Watch: Film Forum, Amazon Prime Video ($3.99)

The Third Man (1949, dir. Carol Reed) — If there’s one thing I’ve learned over the past year, it’s that you can’t go wrong with a Joseph Cotten movie.

The Third Man opens with American author Holly Martins (played by Cotten) arriving in chaotic, post-war Vienna to stay with his childhood friend, Harry Lime (played by Orson Welles), only to find him dead — allegedly. He attends Harry’s funeral and subsequently gets introduced to his late friend’s lover, Anna Schmidt (played by Alida Valli). As the circumstances around Harry’s death growing increasingly suspicious, Holly finds himself catapulted into what Criterion correctly characterizes as a “legendary tale of love, deception, and murder.”

In this twisty noir, Cotten, Welles, and Valli — under Reede’s direction, of course — craft a chilling exploration of morality and corruption, of what constitutes right and wrong. As part of his process, screenwriter Graham Greene developed the story as a novella before translating it over to screenplay form. That practice, from my perspective, strengthens the final script. Consider the following exchange from the film:

Holly: I guess nobody really knew Harry like he did...like I did.

Major Calloway: How long ago?

Holly: Back in school. I was never so lonesome in my life until he showed up.

Major Calloway: When did you see him last?

Holly: September, '39.

Major Calloway: When the business started?

Holly: Um, hmm.

Major Calloway: See much of him before that?

Holly: Once in a while. Best friend I ever had.

Major Calloway: That sounds like a cheap novelette.

Holly: Well, I write cheap novelettes.

Here, Greene underscores a key character detail — specifically, Holly’s profession as a writer — through dialogue, a decidedly novelistic subtlety.

The Third Man not only won the Palme d’Or at the 1949 Cannes Film Festival, but also secured Robert Krasker the 1951 Academy Award for Best Cinematography - Black and White. For the blog Cinephilia & Beyond, Koraljka Suton developed a deep dive on the film; in it, he acknowledges how Australian cinematographer Robert Krasker “contributes to the prevailing gloomy mood of Reed’s picture thanks to [his] usage of wide-angle lens distortions and Dutch camera angles.”

Suton also touches on The Third Man’s score, the film’s tonal glue that succeeds where May December fails. He writes: “Looking for music that would serve as a reflection of postwar Vienna, Reed wanted to avoid the use of sentimental waltzes and accidentally stumbled upon the perfect person to provide the score for his film. The director heard unknown Austrian musician Anton Karas’s music at a production party and promptly asked him to come record demos in his hotel room. Once the movie was shot, Karas traveled to London to write and record the score. The chilling music was performed on a zither and became such a seminal part of the movie and its atmosphere that the instrument was even used in one of its taglines (‘He’ll have you in a dither with his zither.’) When the film was released, ‘The Harry Lime Theme’ became an unexpected smash hit and sold 500,000 copies by the end of 1949 and stayed on top of the Billboard chart in the United States for eleven weeks in 1950.”

Like Days of Heaven, I saw The Third Man in Film Forum, where it will similarly screen through Thursday (1.4). This one, however, is in 35mm!

Where to Watch: Film Forum, Amazon Prime Video (premium subscription)

Alright, that’s it! New year, new newsletter tomorrow. Have fun tonight, and cheers to 2024!

xo,

Najet