Movies of the Month: October [2023]

A month of spooky classics and '50s films

A month of spooky classics and ‘50s films, plus my final review of Whit Stillman’s doomed bourgeois in love trilogy. Here we go:

Barcelona (1994, dir. Whit Stillman) — The chronological second in Whit Stillman’s doomed bourgeois in love trilogy, this verbose comedy of manners, like its comrades, captures the end of a specific era. Metropolitan (1990) distills a waning version of Upper East Side society, one that will mutate but live on in the years ahead, while The Last Days of Disco (1998) chronicles the moment implied by its namesake. Barcelona transports its audience to “the last hot days of the Cold War,” as The New Yorker put it in a 2014 retrospective, where “the story of two young American men in Spain — a naval officer and a businessman — and the young Spanish women they meet depends inextricably on the politics that they encounter with their new friends, and friends of friends, and friendly enemies, and just plain enemies.” Stillman told The LA Times back in 1993: “My jokey formulation for Barcelona is that it’s Metropolitan meets Where the Boys Are meets Year of Living Dangerously. But I said that before and a trade paper reported it seriously. So could you put ‘he joked’ after the quote?”

The narrative centers on expat cousins Ted and Fred Boynton (played by Metropolitan alums Taylor Nichols and Chris Eigeman, aka: fetal Jason Stiles from Gilmore Girls). When snarky naval officer Fred comes to stay with nerdy Chicago businessman Ted, the two navigate, on a lighter note, international dating and, on a darker note, the community’s negative reaction to the sociopolitical implications of Fred’s presence. As Roger Ebert describes in his review of the film, “There's an undercurrent: The presence of these Americans in Spain — one a capitalist, the other a militarist — makes them a target for left-wing groups, and it doesn't help that Fred believes in maintaining a high profile (called a "fascist," he explains, "Young men wearing this uniform died to protect Europe from fascism").” This layer imbues the narrative with a type of tension distinctive to Barcelona, tonally distinguishing it from the trilogy’s other two films.

Shot on location, Barcelona shows a late eighties iteration of the city set to an immersive soundtrack. One of my favorite moments features a winding drive through the Catalonia countryside set to “La Hora del Crepúsculo” by Los Cinco Latinos, a Spanish-language version of “Twilight Time” by The Platters. For me, this scene projects a layered sense of looming finality that comes to define Barcelona, as well as Stillman’s doomed bourgeois in love trilogy at large. (If you’re curious, I loved all three, but my official power ranking is The Last Days of Disco > Barcelona > Metropolitan.)

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video ($2.99)

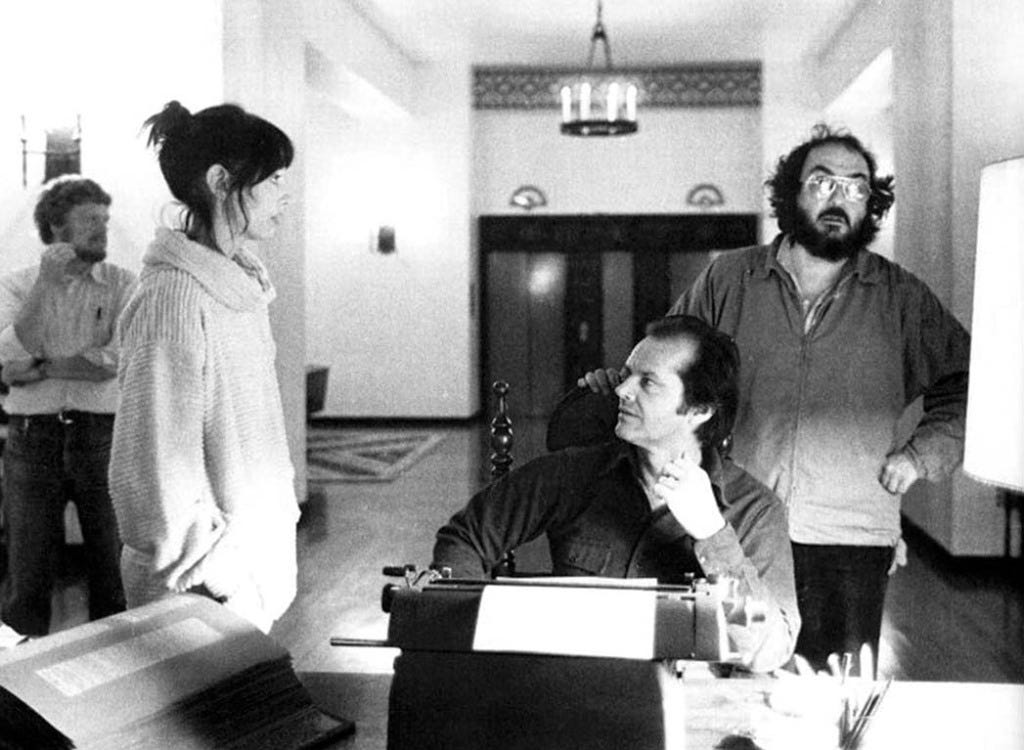

The Shining (1980, dir. Stanley Kubrick) — What can I say about this horror masterpiece that hasn’t been said already? ICYMI: The Shining follows depressed novelist Jack Torrance (played by Jack Nicholson), as well as his wife, Wendy (played by Shelley Duvall), and son, psychic Pisces-coded king Danny (Danny Lloyd), as they take up residence in The Overlook Hotel. Situated in the Colorado wilderness, The Overlook requires a winter caretaker, and Jack volunteers for the job in hopes the isolation will afford him the opportunity to make progress on his novel. But under the influence of the hotel and its residents, Jack’s sanity famously starts to slip.

I view The Shining, at its core, as a film about domestic terror. Stephen King wrote the novel version as a means of analyzing his own alcoholism on a fictional plane. Consequently, the book version of Jack (so I’ve heard — I still need to read the novel) starts off stable until the hotel begins to ravage him, emerging as a kind of allegory. Meanwhile, Kubrick’s Jack begins as an already-less-than-stellar guy, to say the least. In one of the film’s early scenes, Danny has a seizure following a premonition around what will befall them at the hotel, and Wendy reveals to the doctor that Jack previously dislocated their son’s shoulder in a drunken rage. This scene (pictured above) — which Duvall, from my perspective, plays flawlessly, but more on that in a minute — laces the narrative with an undercurrent of violence from the onset.

Reflecting on The Shining in 2006, Roger Ebert wrote:

The actors themselves vibrate with unease. There is one take involving Scatman Crothers that Kubrick famously repeated 160 times. Was that “perfectionism,” or was it a mind game designed to convince the actors they were trapped in the hotel with another madman, their director? Did Kubrick sense that their dismay would be absorbed into their performances?

“How was it, working with Kubrick?” I asked Duvall 10 years after the experience.

“Almost unbearable,” she said. “Going through day after day of excruciating work, Jack Nicholson's character had to be crazy and angry all the time. And my character had to cry 12 hours a day, all day long, the last nine months straight, five or six days a week. I was there a year and a month. After all that work, hardly anyone even criticized my performance in it, even to mention it, it seemed like. The reviews were all about Kubrick, like I wasn't there.”

I personally hate that Duvall had this experience because, from my perspective, her performance functions as the movie’s emotional core. Wendy’s passivity, a quality critiqued by King for its diversion from the source material, heightens the film’s tension by teasing the low-level fear Jack sparks from the outset. In one scene, desperate to focus on his book, Jack lashes out at Wendy for interrupting his work, urging her out of the lobby. Her physical and verbal response — deferential, controlled, downcast — reveals the extent of Jack’s psychological hold. As Wendy reaches breaking point, spurred from avoidance into action, the stakes of the film peak.

Danny Lloyd’s portrayal of his eponymous character similarly fuels the film’s power to evoke fear. At one point, Jack hugs his son; Danny stiffens, his discomfort visible, then audible (“You’d never do anything to hurt me and mom, would you?”). His sweaters feature era- and age-appropriate visuals, from Apollo 11 (pictured above) to Mickey Mouse. These costume choices, paired with the perpetual presence of his toys, coalesce to convey a sense of innocence. At one point, Danny plays with his toy cars until a tennis ball rolls into them, fulfilling the looming threat of disruption, of danger, on a micro scale.

Danny also accentuates The Overlook’s off-season emptiness, his minute physical presence opposing its size. Take, for instance, the iconic scene of him riding his tricycle through the hotel. Sound shifts and echoes as he moves from rug to wood to linoleum and back again. This visual and auditory cue recurs, communicating the Torrances’ day-to-day monotony amidst their isolation.

Kubrick finds moments to convey unnerving quietude through scale beyond Danny’s physicality as well. For instance, several shots show Jack from behind, typing away at his book from the vast, abandoned lobby. Another scene follows Wendy and Danny as they explore the hotel’s outdoor maze, then zooms out to show an aerial view, followed by Jack watching an avatar of their actions from a map inside the hotel (pictured above). This Panopticon effect creates a sense of supernatural foreboding, one actualized in that very space during the film’s final act.

Where to Watch: Max (subscription), Amazon Prime Video (premium subscription)

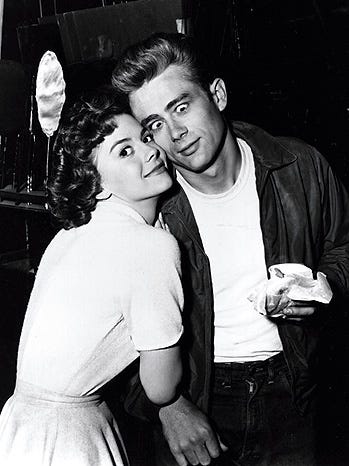

Rebel Without a Cause (1955, dir. Nicholas Ray) — Nicholas Ray’s era-defining examination of teen rebellion opens at a Los Angeles police station with its three main characters under arrest: Jim Stark (played by James Dean) for public intoxication, Judy (played by Natalie Wood) for curfew violation, and John "Plato" Crawford (played by Sal Mineo) for killing a litter of puppies (a plot line I, famously a Pisces, am still trying to block out). Each teen reveals the root of their behavior — Jim’s frustration with his father’s weak character, Judy’s devastation at her father’s inattention, and Plato’s loneliness in the wake of his parents’ abandonment —, teeing up a tale of intergenerational tension and its potential for tragic consequences. By foregrounding each teenager’s perspective, Rebel Without a Cause avoids operating as a McCarthy-era morality tale and instead emerges as the seminal precursor to the scores of stories about troubled teens — from The Breakfast Club (1985) to Less Than Zero (1985) to Beverly Hills, 90210 (1990-2000) — that have graced film screens, novel pages, and television sets in the decades since its debut.

James Dean is just so insanely good (and hot) in this movie. Jim begins the film as the new kid at his local LA high school. Plato lurks in Jim’s shadow, while Jim tries to get Judy’s attention by offering her a ride to school. Instead, she gets picked up by a gang of straight-out-of-Central-Casting greasers, including her boyfriend, Buzz Henderson (played by Corey Allen). From a knife fight at The Griffith Observatory to a “chickie run” (aka: super dangerous car race a la that scene in Grease) off a coastal cliff, Jim soon finds himself embroiled in challenge after challenge, each one designed to prove a certain version of masculinity. The bulk of the action occurs over the course of 24 hours, moving toward a devastating conclusion at breakneck speed.

As Slash Film puts it: “Rebel Without a Cause is deeply concerned with the teenage sense of immortality and risk-taking, the justifications of recklessness. In being the definitive cinematic text on that behavior, it made [James] Dean a legend.” But it’s not just the film’s content, but how Dean plays it, that makes this film a classic. Two particular scenes stand out to me. In the first, Jim debates participating in the “chickie run” and, asking his father for vague advice, receives the expected suggestion to shy away from confrontation of any kind. This reaction, paired with Jim’s desire to become anything but his father, drives him to make the opposite choice. He then recounts the events of the race to his parents, stating: “Dad, I said it was a matter of honor, remember? They called me chicken. You know? Chicken? I had to go. ‘Cause, I didn't I'd never be able to face those kids again.” Rebel Without a Cause disentangles toughness and masculinity, making an alternate case for honor as the defining feature of manhood, a moral quandary perfectly distilled by Dean’s performance.

The film’s iconography and cinematography — from Jim’s red jacket to sweeping shots of The Griffith Observatory — have become the stuff of legend as well. One particularly memorable sequence, both aesthetically and emotionally, transpires at an abandoned house in Los Feliz, with Jim, Judy, and Plato taking refuge from the forces closing in on them. Dean and Wood’s chemistry, from my perspective, serves as a highlight of the film, and it culminates here. But perhaps more importantly, it showcases the safety Jim, Judy, and Plato come to represent for one another. You could easily draw a through line from this moment to the Model Home episode of The OC, with the three primary characters in each instance finding family through each other.

As an aside, I’m convinced this film’s production was cursed. All three stars died young and in horrible ways. A car crash famously killed James Dean at age 24. Natalie Wood drowned under mysterious circumstances (read as: IMO was murdered by her husband, Robert Wagner) off the coast of Catalina Island at age 43. A mugger stabbed Sal Mineo in his West Hollywood parking lot at age 37. Watching Rebel Without a Cause with this hindsight imbues an already fatalistic film with an added layer of foreboding.

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video (premium subscription)

On the Waterfront (1954, dir. Elia Kazan) — Along with Rebel Without a Cause, I saw this film as part of Film Forum’s 50 from the ‘50s series, which I talked about in the October newsletter. Inspired by Malcolm Johnson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Sun stories from the late 1940s, On the Waterfront reveals the violence and corruption lurking amongst dockworkers in Hoboken, New Jersey.

The film opens with prizefighter-turned-dockworker Terry Malloy (played by Marlon Brando) luring fellow longshoreman Joey Doyle (played by Ben Wagner), to a rooftop — and, unintentionally, to his death at the hands of union boss Johnny Friendly (played by Lee J. Cobb). This moment creates a moral dilemma that propels Terry through the remainder of the film. As filmmaker and writer Adam Scovell so aptly put it: “tensions rise as a local priest (played by Karl Malden) is determined to finally break the criminal hold over the workers. Falling for Joey’s sister Edie (played by Eva Marie Saint), Terry must decide whether the trust of his high-up brother (played by Rod Steiger) and the union boss (Cobb), is worth the lives of the men he sees taken advantage of every day.”

Brando and Saint give absolutely phenomenal performances in this film. Vanity Fair called Brando’s depiction of Terry a “revelation” as recently as 2021, while Saint’s portrayal of Edie secured her the 1955 Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress. Per Scovell: “For all of its seething male energy, however, this pressure-cooker of a film is defined as much by its less-celebrated star, Eva Marie Saint. She haunts the film as an almost ethereal presence until her path crosses Brando’s crumbling anti-hero…Through the sheer precision of her performance, she reflects the tough world around her without necessarily being a part of it…She is stillness and light in a world of brutality and darkness.”

Penn State Media Studies lecturer Kevin Jack Hagopian noted: “Kazan, not himself particularly religious, understands the power of religious imagery. There are the job tokens, like Roman coins, scattered among the desperate souls at the shape-up.” A moment defined by this kind of visual served as On the Waterfront’s high point for me; without spoiling specifics, it reveals Edie in her home, dressed in all white, a cross hovering in the background as Terry comes to meet her. The juxtaposition of their exchange with the placement of the crucifix creates a kind of tension between secular and sacred, seemingly mirroring the moral struggle that comprises the core of the film.

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video ($3.99)

Shadow of a Doubt (1943, dir. Alfred Hitchcock) — Wow, what an absolute banger. Hitchcock cited Shadow of a Doubt, which holds a 100% score on Rotten Tomatoes, as his favorite of his films for a reason. Genuinely, five stars, no notes.

This noir centers on the Newtons, a “typical American family” residing in Santa Rosa, California. Eldest daughter Charlotte, aka: Charlie (played by Theresa Wright), bored with the monotony of their existence, resolves to write her favorite uncle and namesake, Charlie (played by Joseph Cotten), to come stay with them for a bit. Before she can even dispatch her telegram, Uncle Charlie arrives at the Newtons’ house for an uncannily timed visit.

I want to stay especially mindful of spoilers for Shadow of a Doubt because so much of the viewing pleasure stems from its twists and turns. What I will say is that this early-stage Hitchcock, as I see it, builds suspense primarily through its structure. Uncle Charlie gives shady, predatory, and borderline incest-y vibes from the beginning, but the true nature of his character remains hidden for the first quarter of the film. This narrative pacing simulates the paranoia experienced by his niece for the audience, creating a particularly potent kinship between character and viewer as the story reveals itself in full.

In his review, Roger Ebert noted: “The town and the Newton family play major roles in the film, and may reveal Hitchcock's own inner feelings. He shot in late 1941 and early 1942, at the outset of World War II, at a time when he was unable to visit his dying mother in London because of wartime restrictions. He later credited the friendliness of the town for making this the most pleasant of all his film locations. His emphasis on the comfy Newton home, a chatty neighborhood, a corner cop who knows everyone's name, the nightly meals around a big dining table — all add up to a security that both he and Uncle Charlie were seeking.” Uncle Charlie operates as an outside force. Consequently, his presence in and of itself operates as a form of disruption, disturbing deep-seated familiarity and, in turn, propelling the plot.

Hallmarks of Hitchcock’s directorial style — from zoomed out staircase shots to close-cut frames of facial expressions — transform the quotidien into the uncanny. Ebert continues: “Not many directors were fonder of staircases than Sir Alfred…The flow at the house goes up the sidewalk, onto the porch, through the door and directly up the stairs. There are outside stairs in the back, and both staircases are used for tight little sequences of threat and escape. Notice how many variations of camera angles and lighting Hitchcock uses with the stairs. He considered them an ideal device for introducing imbalance into otherwise horizontal interiors. So important were they to him, so memorably used, that I can name some of his titles and if you've seen them you will instantly recall the stairs: Notorious, Psycho, Strangers on a Train, Frenzy, and, of course, Vertigo.”

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video ($3.99)

That’s all for now — see you at the end of November!

xo,

Najet