Happy Last Day of August! Going forward, book and movie reviews will drop on the last day of the month, followed by the newsletter on the 1st, to overwhelm you with three long-ish emails over two days instead of one incredibly long email on one day.

Okay, here we go:

The Last of Her Kind by Sigrid Nunez (2005) — This novel follows Georgette George and Ann Drayton, two freshman roommates at Barnard in 1968. While Ann hails from a wealthy Connecticut family, Georgette comes from a working class town in upstate New York. Told more or less entirely in first person from Georgette’s perspective, The Last of Her Kind falls into the narrative family of Bret Easton Ellis’s latest novel, The Shards. The first third of the book traces Georgette and Ann’s freshman and sophomore years chronologically, then splinters into a less linear memory story that carries through to the early 2000s.

Skillfully interweaving historical detail, Nunez captures the sharp cultural shift that delineated the 60s and 70s on individual and collective levels, how that distinction and its fallout came to define a generation. Social issues ranging from class guilt to racial discrimination to the state of American prisons drive the story through the personal prism of two distinctive women on markedly different paths. The novel avoids the temptation of telling you what to think, as all good fiction does, in my estimation. Instead, it shows ideologies taken to their most extreme iterations, teasing out the layers beneath the cultural moments it captures.

The prose, while masterful throughout, shines in one particular section for me. Georgette, preparing to reveal the great love of her life to the reader, explains why she must shift from first to third person: “Now here comes the part where I tell about Love. Here is some advice I once read, from one writer to another: ‘The trick is to be cold about the hottest thing there is: love.’ But that writer was talking about fiction. Trial and error has shown I cannot accomplish this difficult thing unless ‘I’ becomes ‘she.’” This change in perspective might feel like a gimmick in the hands of a less accomplished writer, but Nunez manages to craft some of the book’s most poignant chapters using this technique.

As Andrew O’Hehir put it in his 2006 review of the novel in Salon: “Building in scope and excitement as it goes, [The Last of Her Kind] blossoms into a powerful and acute social novel, perhaps the finest yet written about that peculiar generation of young Americans who believed their destiny was to shape history.”

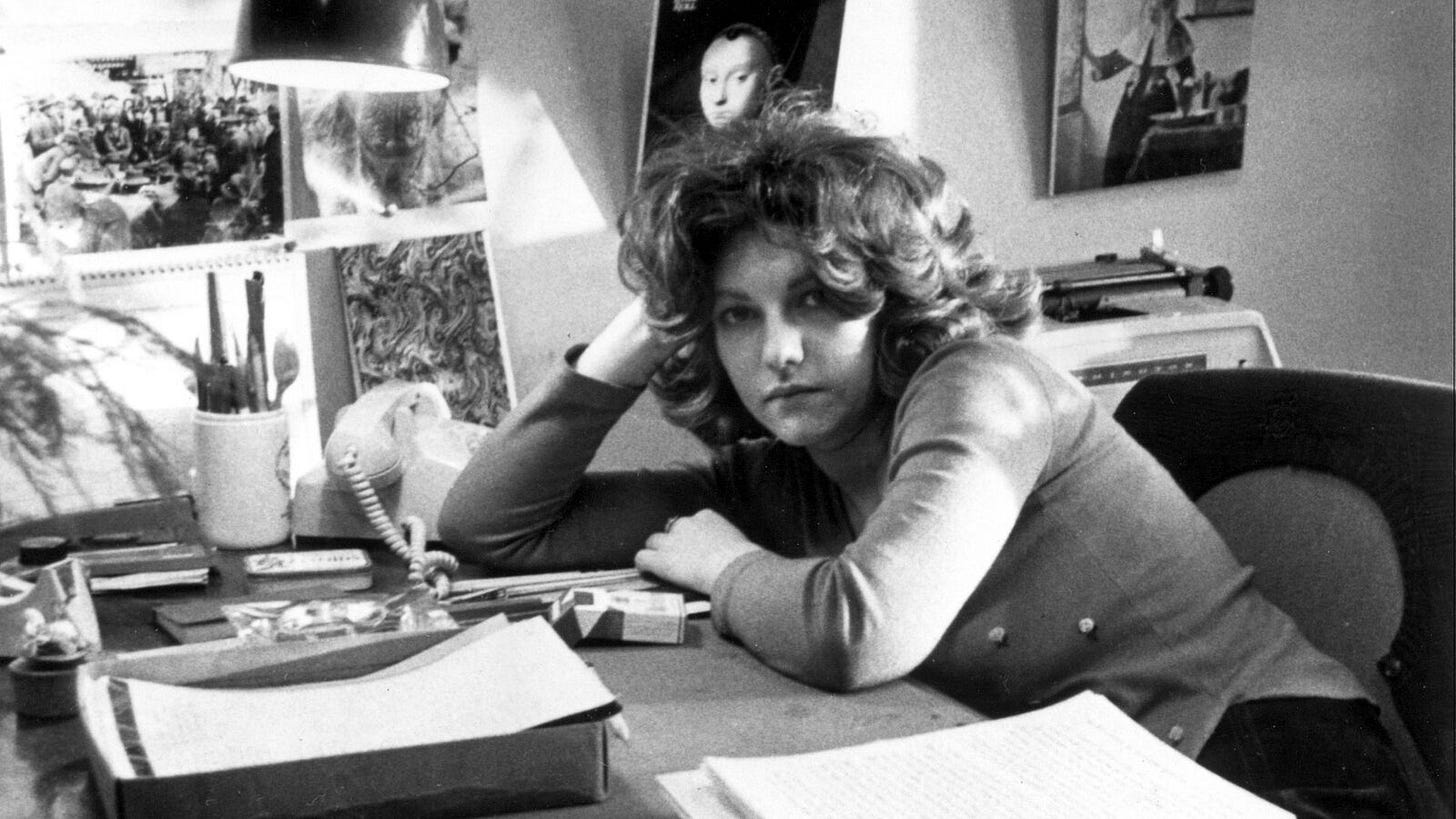

A Woman’s Battles and Transformations by Édouard Louis (2022) — Translated from French into English by Tash Aw, A Woman’s Battles and Transformations opens with the description of a photograph, an image of the author’s mother, age twenty, “everything about the snapshot…evok[ing] freedom, the infinite possibilities ahead of her, and perhaps, also happiness.” The subsequent 100 pages go on to reveal how she fell from that freedom, then clawed toward it again, over the course of 25 years.

Shifting between second and third person across a non-linear narrative, A Woman’s Battles and Transformations operates as both memory and manifesto. Through flashes of history, vignettes of recollection, now-30-year-old Louis looks back on his mother’s story, speaking to and about her. Through the lens of a particular individual, the narrative showcases how class and gender structures conspire to constrain potential.

Louis reflects on his own complicity, how and why he began to sympathize with his mother’s plight, and their dual class ascensions — his at the hands of education and success, hers at the hands of a long-awaited divorce. These musings culminate to create a tender family portrait, one that makes the case for change and happiness as one and the same, sadness and liberation as two sides of the same coin.

The Map and the Territory by Michel Houellebecq (2005) — Translated from French by Gavin Bowd, this novel functions as part faux artist history, part crime procedural. Winner of the 2010 Prix Goncourt, it embodies the experimentalism synonymous with so much of French contemporary fiction, with The Guardian praising it as a “wonderfully strange and subversive enterprise.”

The first two thirds of the novel trace the life and career of fictional artist Jed Martin, delving into his relationships with women, his father, and a fictional version of Houellebecq. A particularly poignant section encapsulates the essence of aging parent-child relationships through the lens of Jed and his father: “He’d never heard him speak like this, even as a child…his father had just relived, for the last time, the hopes and failures that formed the story of his life…for the two to three minutes this took, Jed had the fleeting, contradictory impression that they either had just started a new stage in their relationship, or would never see each other again.”

Told in third person, the prose drips with irony and dry humor. For instance: “Ferber had no difficulty getting Jed on the phone: he was at home; no, he was not disturbing him. In reality, yes he was, a little bit, as Jed was watching an anthology of DuckTales on the Disney Channel, but he abstained from adding that.”

Elements of the structure and characterization, however, failed to land for me. The novel transforms into a police procedural somewhere around page 175 (of 269). While I enjoyed the unlikely combination of genres, the mystery itself seemed rushed to me, wrapping up so quickly that any initial tension sparked by the murder dissipated over the course of 10 or 20 pages.

Moreover, Houellebecq’s choice to insert himself into the story feels masturbatory. Now, this perspective might seem a bit hypocritical coming from me since, as you well know, I love Bret Easton Ellis’s The Shards (2023) and Lunar Park (2005), both of which feature fictional versions of the author. The difference? Both of those novels take the time to craft and reveal the emotional lives of those fictional avatars, the extent of their overlap with Ellis’s real thoughts and feelings ambiguous — and, ultimately, unimportant, tangential to the world of the novel in question.

The Guardian’s review of The Map and the Territory praises Houellebecq’s fictional doppelgänger, stating: “An amalgam of the information and hearsay that we have about him ("It was public knowledge that Houellebecq was a loner with strong misanthropic tendencies") and a vehicle for fragmentary and provocative pronouncements about literature ("I think I've more or less finished with the world as narration – the world of novels and films, the world of music as well. I'm now only interested in the world as juxtaposition – that of poetry and painting"), his existence has the reader dancing around the blurry lines between facts and fiction.” That’s all well and good, who is he beyond hearsay and opinions? What constitutes his emotional life?

Real-world figures beyond Houellebecq populate the world of the novel, but they operate as a cultural chorus, their collective presence creating context, functioning as a form of set dressing. Meanwhile, Houellebecq dominates the narrative as an individual. Consequently, his internal emptiness renders repeated interjections like “the author of Platform agreed heartily” more inescapably aggravating than clever, from my perspective (see my margin notes, including “omg AGAIN,” “we get it, it‘s you !!,” and “stoppp”).

A Big Storm Knocked It Over by Laurie Colwin (1993) — Before I talk about this novel specifically, I’m legally obligated to discuss how much I love Laurie Colwin. Her work has experienced a bit of a renaissance since her two recipe books, five novels, two short story collections got reissued with Instagrammable covers in 2021. I came across her first novel, Happy All The Time, through the team at Three Lives & Company that year and have since read almost everything she has published.

Simply put, reading Colwin feels like sipping hot soup on a cold day — but not just any old soup. Beef, leek, and barley soup with an added spice you can’t quite identify. On the surface, her work seems simple, straightforward. Colwin’s heroines hail from upper middle class backgrounds and very much reflect the context of their eras, primarily preoccupied with relationships, child-rearing, and, above all, building and maintaining happy homes. This description might make her writing sound dated, which, in some aspects, it is. But, at the same time, Colwin considers female pleasure and what constitutes happiness in marriage with a depth, a defiance against societal constructs, many contemporary writers have yet to explore.

As The New York Times put it in a 2021 piece, “The Sneaky Subversiveness of Laurie Colwin,”: “That Colwin presents adultery not as destructive but as soul-nurturing is one of the most surprising features of her plots. A husband is not — should not be — a woman’s everything. ‘I’m right to love him, and I’m right to love you,’ Olly [from Shine On, Bright and Dangerous Object] tells her married lover before returning home to her live-in boyfriend. Women in American fiction rarely dally away from their beloveds with this kind of guilt-free abandon.” Family Happiness, published in 1984, most acutely reconsiders traditional notions of monogamy and fidelity, giving its central character, Polly, an ending decades ahead of its time.

The New York Times piece goes on: “It’s instructive to consider how the Colwinian sensibility — call her ‘a strong domestic sensualist,’ as she dubs one of her heroines — holds up, given that her characters typically wind up in traditional nuclear families (by current standards) and take their privilege for granted. How are we to feel about men who have special socks mailed to them in New York from Paris, or about wives so devoted that they assemble trays of sumptuous goodies for their workaholic husbands’ late-afternoon snacks? Although her unions may feel a bit candy-colored at first, it turns out that Colwin herself is intent on probing such domestic comfort…Beneath the effervescent romcomedies of manners, Colwin sneaks in a hint of ironic European art-house movie, with more moral ambiguity, less happiness all the time, than the plots might lead you to expect.”

Her work addresses joy, but, within that, the precariousness of it, layering her plots with tinges of anxiety. This undertone of instability feels most prevalent in A Big Storm Knocked It Over, her final novel, published posthumously following her death from an aortic aneurysm at age 48. In this book, our central character takes the form of Jean Louise Parker, a newly married Manhattanite embarking on motherhood. While anxiety around her relationship, around family life, figures prominently, the novel also explores Jean Louise’s feelings about change more broadly. News of an impending sale leaves her, a book cover designer at a publishing house, reeling. Her desire for a thrice-married coworker bubbles in the background. Her friend, Dita, puts subtle yet abrupt distance between them, capturing the essence of passive aggressive female friend breakups. Jean Louise’s world stays polished from start to finish, but the small cracks in it, the fractures that feel massive to her, underscore the universality of existential dread, how it persists even in a seemingly cozy, Nora Ephron-esque world.

If you’re new to Colwin, most people recommend starting with Happy All The Time, but that approach might leave you with an overly “candy-colored” perception of her work. I’d suggest starting with Family Happiness or Home Cooking. The former strikes me as the most developed of her novels, while the latter should give you the strongest sense of her voice. A contributor to Gourmet magazine for years, Colwin amassed a following for her food essays, which embed recipes with fun personal anecdotes. (Also, true story: her gingerbread recipe is my cat’s favorite food.)

The Summer Book by Tove Jansson (1972) — Written by Moomins mastermind Tove Jansson in the wake of losing her mother, The Summer Book weaves a portrait of the thin line between humans and nature, life and death, through a series of 22 vignettes. Each one follows a summertime adventure undertaken by a girl named Sophia and her grandmother, both of whom reside on a remote Finnish island with Sophia’s father. The seemingly recent death of Sophia’s mother garners a two-line mention near the book’s beginning, setting its emotional undertone: “One time in April, there was a full moon, and the sea was covered with ice. Sophia woke up and remembered that they had come back to the island and that she had a bed to herself because her mother was dead.”

This book is, simply put, incredibly special and made me want to call my grandma. Jansson crafts lyrical prose (translated from Swedish by Thomas Teal) that captures tragedy and comedy in equal measure, presenting extreme youth and old age as parallel experiences marked by supervision and play. In one particularly entertaining scene at the beach, Sophia’s father goes swimming, and Grandmother sneaks off for a cigarette. Sophia finds her and promises not to tell, cementing them as co-conspirators in a world where adults — adults ages 18 to 65, that is — hold the power. The two go on to weather storms both literal and metaphorical throughout the elliptical narrative. One sequence shows Sophia and Grandmother building a miniature representation of Venice in a marsh pool, relying on Grandmother’s memories of past travel to construct streets and landmarks out of wood and stone. When a storm destroys it, humanity at the mercy of nature, Grandmother rebuilds to shield Sophia from the truth.

Jansson distills the crystalline fear, sheer anxiety, that bubbles in children marked by trauma. In one chapter, Sophia insists on sleeping with her father’s ratted old robe, gripped with fear that he may not make it through a storm, back to the island. Death lurks beneath life, its weight pressing against the story ubiquitously, consistently. At another point, the narrator recounts: “Sophia picked up some flowers and held them in her hand until they got warm and unpleasant; then she put them down on her grandmother and asked how God could keep track of all the people who prayed at the same time.”

The Summer Book functions as a meditation on memory — and a memory itself. Taking place across multiple summers in no particular order, the various vignettes weave and memorialize moments that transcend, stay freed from, the confines of time. Within that, the novel reveals how meaning can fade with age. One particularly poignant sequence reveals that Grandmother “had been a Scout leader when she was young, and, in fact, it was thanks to her that little girls were even allowed to be Scouts in those days.” When Sophia urges Grandmother to tell her more in the midst of a camping expedition, the narrator reveals: “A very long time ago, Grandmother had wanted to tell about all the things they did, but no one had bothered to ask. And now she had lost the urge.” Grandmother goes on to ruminate: “And unless I tell it because I want to, it’s as if it never happened; it gets closed off and then it’s lost.” Jansson makes the case for storytelling — specifically, the “urge” to tell stories — as the antidote for loss.

Remarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van Pelt (2022) — This debut has topped multiple bestseller lists, lauded by the likes of Kirkus Reviews as a “charming, warmhearted read.” Chapters alternate between first and third person. A giant Pacific octopus named Marcellus narrates the first-person chapters, while the third-person ones tease out the lives of townspeople in a fictional Pacific Northwest town called Sowell Bay, focusing predominantly on aquarium cleaners Tova and Cameron.

From my perspective, Van Pelt shows instead of tells in a way that flattens narrative tension. The characters’ histories, motivations, and dynamics get spelled out, leaving no space for inference or thought from the reader. In the immortal words of Bill Nye, consider the following [passage]:

“She was always such a sweet girl. I never got why she chose Brad over you.”

“Aunt Jeanne!” Cameron groans. He must’ve explained a million times; it was never like that with Elizabeth.

“Well, I’m just saying.”

Cameron, Brad, and Elizabeth were best friends growing up; the three musketeers. Now, somehow, the other two are married and having a baby. It’s not lost on Cameron that the tot’s going to take the place as Brad and Elizabeth’s third wheel.

Now, an alternate edit:

“She was always such a sweet girl —”

“I don’t want to talk about it,” Cameron says.

“I never got why she chose Brad over you.”

The first exchange, the one that appears in the book, states character dynamics outright, while the latter edit leaves more to the reader’s imagination. Version two allows for slow introduction of detail, of backstory, heightening the reader’s curiosity and, by extension, investment.

Van Pelt struggles to distinguish her characters through dialogue as well. Another excerpt reads:

Tova shakes her head. “He left. He went back to California.”

“What?” Avery’s mouth drops open. “Why?”

“That’s a rather complicated question.” Tova’s tone is measured. She sinks back to her spot on the bench, and the girl sits at the other end, tucking her bare legs underneath her. Tova goes on, “I suppose, in his mind, too many misunderstandings.”

Avery’s eyebrows knit together. “Misunderstandings?”

“His words exactly.” She raises a brow at the young woman. “I’m quite certain he thinks you are…oh, how did he put it…ghosting him?”

With the exception of Tova’s final phrase (“I’m quite certain he thinks you are…oh, how did he put it…ghosting him?”), an in-your-face attempt to underscore her advanced age, the two characters sound identical. Van Pelt also spells out tones and mannerisms, over-indexing on descriptions of eyebrow movements instead of leaving space for the reader to imagine those details. Now, another edit:

“Left. Went —” Tova says.

“What?” Avery says.

“ — back to California,” Tova says.

“Why?” Avery says.

“A bit of a complicated question. I suppose, in his mind, too many misunderstandings,” Tova says."

“Misunderstandings?” Avery says. “Like, what kind of misunderstandings?”

“Said he thinks you’re ‘ghosting him,’” Tova says.

In this alternate version, Tova and Avery have different manners of speaking. Tova drops her pronouns. Avery uses “like” and, perhaps most importantly, interrupts. How often do you engage in a conversation — especially an emotionally charged one — without talking over someone? Van Pelt’s dialogue consistently leaves her characters pausing, waiting politely, in a way that rarely aligns with life.

Beyond dialogue, the prose itself suffers from an overbearing narrative presence. At one point, Van Pelt writes: “Traffic is horrible leaving Seattle, but Cameron couldn’t tell you whether he’s been sitting in gridlock for ten minutes or three hours.” In How Fiction Works, James Wood distinguishes between indirect style and free indirect style, exemplifying the former as: “He looked over at his wife. She looked so unhappy, he thought, almost sick. He wondered what to say.” Meanwhile, Wood offers this example of free indirect style: “He looked at his wife. Yes, she was tiresomely unhappy again, almost sick. What the hell should he say?” He underscores free indirect style as the ideal register for modern fiction because “internal speech or thought has been freed from authorial flagging.” Wood elaborates: “Note the gain in flexibility. The narrative seems to float away from the novelist and take on the properties of the character, who now seems to ‘own’ the words.” Van Pelt’s prose, as I see it, falls somewhere in between indirect and free indirect style, and it would benefit from a more overtly embracing the latter. Consider a final alternative edit: “Traffic, complete gridlock, encircles Cameron. Ten minutes of staring at that sign? Or three hours?” This version softens the narrator’s touch, deflating the space between reader and character.

This review might seem overly detail-focused (#VirgoSzn), but details matter when it comes to developing characters, crafting a world. Reading this book felt like riding a bike with training wheels at an advanced age; Van Pelt clutches her reader’s hand through each page instead of trusting their imaginations to meet her halfway.

Okay, that’s it! Keep an eye out for August movie reviews later today and the September newsletter tomorrow.

xo,

Najet