Earlier this year, my friend Ama (hi, Ama) introduced me to a virtual book club run by Los Angeles-based librarian Alana May Johnson. Each month, Johnson selects two books for members to choose between, then ships out the respective selections. Her thoughtful choices have introduced me to a handful of wonderful novels, from Paula Fox’s Desperate Characters to Tom Drury’s The End of Vandalism.

While Johnson’s book club unfortunately wrapped up in November, I started the month with a some of her picks to catch up on, and all three of these novels came from that pile. Without further ado:

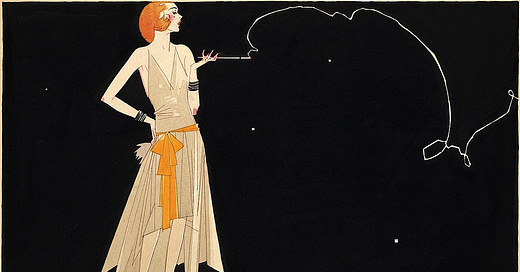

Ex-Wife by Ursula Parrott (1929) — Wow. Ursula Parrott walked so Candace Bushnell could run. Before Bushnell’s Carrie Bradshaw, the single girlies of New York had Parrott’s Patricia, a Jazz Age divorcee navigating the trials and tribulations of dating in the city. This novel scandalized and enthralled audiences when it first published anonymously in 1929 and has experienced a sort of renaissance recently thanks to its McNally Editions reissue.

Told in first person, Ex-Wife opens in 1928 with Patricia’s declaration that her husband, Peter, left her four years ago. The narrative then loops back to the waning weeks of their relationship in 1924 before chronicling Patricia’s move in with her roommate-turned-best friend, Lucia, and adventures in post-divorce dating. The notion of The New Woman that came to define the 1920s colors the narrative, with much of the story centered on advertising girlies Patricia and Lucia finding their way in a still-repressive moment of so-called female liberation.

Ex-Wife captures the city’s unchanged mood through the shared experiences of operating as a single woman in New York. At one point, Patricia narrates: “At the Waldorf, I wanted to tell her [Lucia] that I loved sharing an apartment with her, and that I liked her better than any woman I had ever known — but Lucia and I were inarticulate with each other about things like that. So we talked of places Lucia and Sam would visit, and things I wanted her to get me in Paris, and ate tomato en gelée, and lobster, and alligators pears — the preposterous sort of meal women order when they are dining together. Warm summer dusk deepened along the Avenue outside.” To me, this excerpt captures a familiar, late May feeling of summer descending on the city, a moment infused with knowledge of lonely months ahead as friends escape abroad. Specific locations even remain unchanged, with Patricia asking a date to meet her at Caffe Dante on MacDougal at one point.

Parrott’s smooth prose possesses a startling sense of modernity as well (“Men told Lucia I was lovely looking, but completely cold. Why cold? I let them kiss me when they must, in cabs, dancing in hot nightclubs, at parties. They were not real. Neither was the office. Clothes were real.”). A master of subtext, Parrott takes a Chekhovian approach. (For context, in dramaturgical analyses, Shakespeare and Russian playwright Anton Chekhov frequently get positioned on opposite ends of the spectrum. In Shakespeare, each character’s every thought and feeling appears on the line. Chekhov, however, buries intent beneath often unrelated dialogue.) Parenthesis distinguish Patricia’s interior thoughts from her external actions, underscoring the existence of a breach between the two [“(Being civilized means that one keeps one’s words unrelated to one’s thoughts, when necessary.)”].

These elements coalesce to weave a nuanced, layered depiction of modern marriage through the lens of heartbreak. Parrott — and, by extension, Patricia — presents the institution as duty disentangled from feeling, prompting a still-relevant reconsideration of its value.

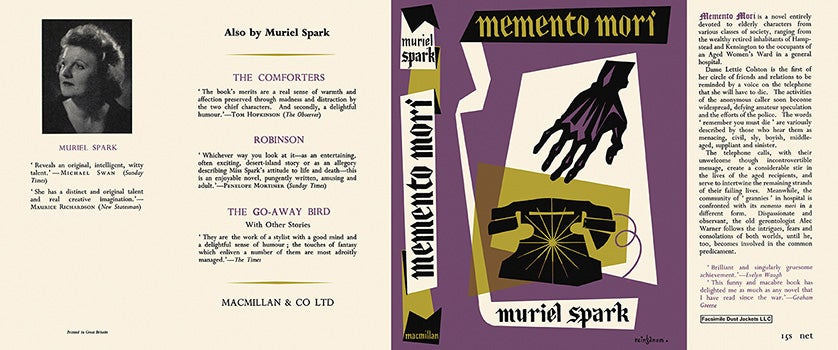

Memento Mori by Muriel Spark (1959) — In his 1959 New York Times review of the novel, now-deceased writer, editor, and translator Robert Phelps writes: “Muriel Spark has mixed a touch of Agatha Christie with some of the swift, slightly brutal comedy of Evelyn Waugh to produce a novel about death that ought to tease, entertain, and quietly perturb a wide variety of American readers.” The quintessence of black comedy, this distinctively British meditation on death and old age centers on a group of elderly friends and acquaintances in London receiving repeated anonymous phone calls. The voice on the other end changes — sometimes young, sometimes old, sometimes male, sometimes female —, but its message remains consistent: “Remember you must die.”

Subtlety serves as the defining feature of Memento Mori, with Spark omitting just enough detail to build suspense. Consider an excerpt from the opening page:

The telephone rang. She lifted the receiver. As she had feared the man spoke before she could say a word. When he had spoken the familiar sentence she said, “Who is that speaking, who is it?”

But the voice, as on eight previous occasions, had rung off.

Dame Lettie telephoned to the Assistant Inspector as she had been requested to do. “It has occurred again,” she said.

In these initial moments, the reader has no grasp on the nature of the “familiar sentence” or why it prompts Dame Lettie to contact the Assistant Inspector. That lack of insight piques curiosity through slow introduction of context, whereas a lesser novelist might have opened with this alternate edit:

The telephone rang. She lifted the receiver. As she had feared the man spoke before she could say a word.

“Remember you must die,” he said.

“Who is that speaking, who is it?” she said.

But the voice, as on eight previous occasions, had rung off. Dame Lettie telephoned to the Assistant Inspector as she had been requested to do. “It has occurred again,” she said.

That change might seem minor, but, by omitting the dread-inducing phrase itself, Spark layers an additional sense mystery on top of that of the caller’s identity.

Aspects of the prose, as I see it, take a page from Virginia Woolf; for instance, the reader learns about the various characters through their solitary action (“Alec Warner lifted the house phone and ordered grilled turbot. He sat to his desk, opened a drawer and extracted a notebook; this was his current diary which would also be destroyed at his death.”). In her 2005 introduction to Mrs. Dalloway, Bonnie Kim Scott draws a parallel between Woolf and James Joyce, noting how “both enter the consciousness of their characters for extended periods and register variations in their energy levels and moods. Both make an unexpected switch from the character who seems to be central at the start of the novel to an outside figure, establishing unusual connections that cross ethnicity, class, and age.” The same assessment could apply to Spark, save for any focus on ethnicity. Memento Mori introduces Dame Lettie in the initial chapter before switching over to the perspective of Jean Taylor, her sister-in-law’s former maid, a character ten years younger who occupies a wholly different societal place.

I really enjoyed this novel, but I do think you have to be in the right mood for it. The first time I started it, I was laying by the pool in California and had a hard time tapping into the narrative despite registering the obvious quality and humor of Spark’s prose. I found myself distracted and confused by the extended cast of characters, something Phelps critiques in his review, toward the book’s start. (Jean Taylor, mentioned above, resides at an old folks’ home among half a dozen other elderly women who all go by Granny plus their last names, rendering them nearly indistinguishable at the second chapter mark.) But, revisiting Memento Mori in London last month, I clicked into Spark’s style and story immediately.

Will and Testament by Vigdis Hjorth (2016) — This hypnotic novel from Norwegian author Vigdis Hjorth opens with two paragraphs that read: “Dad died five months ago, which was either great timing or terrible, depending on your point of view. Personally, I don’t think he would have minded going unexpectedly; I was even tempted when I first heard to think he might have fallen on purpose, before I knew the full story. It was too much like a plot twist in a novel for it to just be an accident. In the weeks leading up to his death, my siblings had become embroiled in a heated argument about how to share the family estate, the holiday cabins on Hvaler. And just two days before Dad’s fall, I had joined in, siding with my older brother against my two younger sisters.”

This opening soliloquy from narrator Bergljot operates as a kind of thread, one that unspools and shapes the narrative over the course of the next 300 plus pages. A propulsive story of inheritance and abuse, Will and Testament embodies trauma through its elliptical form. Time flattens, mimicking the conflation of past and present that often accompanies complex PTSD, while repetition distinguishes the prose. Specific phrases get meditated upon, revisited repeatedly, while moments past and present recur with increasing detail until the full picture sharpens into view. Hjorth’s writing could serve as a master class in punctuation; commas substitute periods, shaping the looping hyper-fixation that comes to define of Bergljot’s stream of consciousness (“I tried to open my mind towards Lars so that his harmless dreams could flow into mine, I tried to suck the dreams out of his sleeping body, but it didn’t work, there was no way in, I was trapped inside myself.”).

The novel operates as a chilling meditation on not only poisoned families, but also on the relationship between perpetrator and injured party, on the nebulous notion of who has the right to claim the position of victim. Hjorth draws in apt cultural, political, and psychological references — from A Doll’s House to Israel-Palestine to Jungian psychology — to tease out the complexities of these dynamics. Respectability politics play a predominant role, with Bergljot’s younger sister, Astrid, persistently presenting politeness and pleasantries as forms of virtue (“Anger wasn’t good. Astrid wouldn’t stoop to anger, Astrid wanted to act in a civilised manner, with dignity and without contributing to the escalation of the conflict, which anger might very well do, Astrid wanted to bring about peace and reconciliation by acting calmly and in a conciliatory manner, perhaps she looked down on people who acted in anger, who couldn’t control themselves, who were ruled by such a primal emotion as aggression.”).

First published in Norway in 2016, Will and Testament got translated into English and distributed in the United States three years later. The occasion of its reissue provided a new opportunity for Hjorth to talk about the novel — and the tabloid blitz that accompanied its initial Norwegian publication. The book sparked a violent reaction from Hjorth’s family, with her sister, Helga, notably a human rights lawyer like Astrid, responding “to the book by writing a novel of her own, Fri Vilje (Free Will), in which a character suffers the trauma of living with the public fallout from a narcissistic sibling's ‘dishonest’ autobiographical novel,” per The Guardian.

In an interview for LARB, London-based culture writer Hannah Williams poses the following question to Hjorth: “When Will and Testament was released in Norway, the press was more focused on autobiographical elements, rather than asking about the book itself. I wanted to know if you thought the Norwegian media did a disservice to the book by focusing on those autobiographical elements?” Hjorth explains: “I was not surprised. That was because I know my family. My sister has written a revenge novel, where she paints a very different picture of my family. And that has forced me to talk about the novel in another way. I can’t say that there’s nothing from reality, because she has proven it. But you know, when my family understood that I was going to write about what they call ‘that,’ they started to make plans. And it was my family that gave that information to one of the biggest newspapers in Norway, and it was so tempting for the newspaper to use it.”

In the same interview, Hjorth characterizes Will and Testament as a novel about “what it’s like not to be heard,” as a vessel for conveying emotional truth. She discusses the distinction between memoir and fiction, explaining “when I insist that Will and Testament is a novel, it’s because it isn’t my mother — you can maybe see something similar between the two — but it isn’t. And that’s why I don’t use names of existing persons. And Bergljot is not an author, she’s an editor of a theater magazine. And because of that I can write about Ibsen, Marina Abramović, all that kind of stuff. If I had made her a teacher, I would maybe have some scenes from the classroom — after every decision I take, the novel moves from reality and makes a kind of system for itself.”

This explanation, of course, brings to mind The Shards, in which Bret Easton Ellis notably gives the narrator his name, while fictionalizing the equivalents of his high school classmates. The novel even includes a disclaimer just prior to the author photo on the back flap, a reprint of Bret’s senior yearbook picture, underscoring that all the characters are fictional apart from its narrator. In the case of both Will and Testament and The Shards, the choice to develop a novel rather than a memoir frees its authors from the shackles of fact, giving them the reins to reflect a more precise emotional truth. As you might recall, I discussed this binary between factual and emotional truth in my October review of Eliza Clark’s Penance, an In Cold Blood pastiche that establishes “a blurred binary” between the two concepts. All three novels, from my perspective, position factual truth as the seed, emotional truth as the plant.

Keep an eye out for November movie reviews later today and a ~festive~ December newsletter tomorrow!

xo,

Najet