A Look Back: October Book Review [2023]

Vegan finance bros, murderous Tumblr teens, Priscilla Presley, etc.

Happy Halloween! As you sit down with your breakfast candy corn, please ~join me~ for a look back on an eclectic month of reads. Here we go:

The Vegan by Andrew Lipstein (2018) — As author Andrew Lipstein (pictured above) said in reviewing his own novel on Goodreads: “One of the best, if not THE best, book about veganism and and high finance out.” So true.

Per The New York Times: “Like Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Vegan (2018) features young marrieds mulling conception and living in a highly desirable part of New York City — then, a four-room apartment in a Victorian building on the West Side of Manhattan; now, a brick townhouse in Cobble Hill— and a dinner party where a guest is effectively roofied. Only here the perpetrator is the protagonist, one Herschel Caine (which, were you to consult a naming dictionary, translates roughly to “deer killer”): partner at a quantitative hedge fund, with $2.8 million in his bank account, growing qualms about his line of work and a keep-up-with-the-Joneses anxiety about his neighbors, one of whom is a Guggenheim.”

When drugging his wife’s friend, Birdie, with a ZzzQuil cocktail births unintended consequences, Herschel becomes wracked with with guilt. His mental state starts to slip, and a strong, almost supernatural kinship with animals emerges. Toeing the line between magic and realism (“This was the power of my imagination, I reminded myself, this was only a punishment inflicted by one part of me on the rest.”), Lipstein constructs a brilliant social satire fueled by a Brooklynite Patrick Bateman with a conscience (“I signed in to my computer and checked the market. The S&P was up 0.71%, the Dow 0.63%, the NASDAQ 0.66%. This was no longer relevant to my work but it was an old habit, a score I checked like the Knicks…Continuing my sign-in ritual I checked my bank accounts — $2.8 million, all combined.”).

Lipstein takes a formal risk about three-quarters through the book that I found particularly effective, one also implemented by Sigrid Nunez in The Last of Her Kind. When Herschel reaches a state of complete dissociation, the novel switches from first to third person to reflect his disembodiment. The choice might have felt gimmicky in the hands of a less capable writer, but Lipstein, like Nunez, leverages it to accentuate and move the reader deeper into the narrator’s mental state. When Herschel finally reaches a moment of catharsis, his first-person perspective returns, but not without continued qualms: “They talked and talked. The less I took part the less I had to see myself as an actor. But the relief didn’t last long, the more I was just the viewer the more I felt the screen in front of me, and there was nothing to do but watch, and it was a meaningless show, there was no central concept or conceit, it didn’t explore anything at all…I felt nothing, and now I wanted to feel that hate. I wanted to feel anything.”

The Times again: “His [Herschel’s] many perambulations and monologues are like a dark retort to TikTok’s self-affirming Hot Girl Walks. They’re those of a man coming undone, realizing he’s a prisoner in an urban cage he helped to build, one where machines reign so supreme that he owns a white-noise generator to dull the sound of morning birdsong.”

Death Valley by Melissa Broder (2023) — As you may recall, in the October newsletter, I mentioned a then-upcoming talk between Melissa Broder and Belletrist co-founder Karah Preiss, which I attended in tandem with the launch of Broder’s latest novel at The Center for Fiction. The conversation revealed a thin line between the narrator in Death Valley and Broder, who repeatedly referred to the narrator as “I” before catching and correcting herself.

In 2021, Broder’s father passed away after spending months in the hospital, the result of a car crash that proved fatal. During his hospitalization, she drove back and forth between her home in Los Angeles and her sister’s house in Las Vegas. Passing through Death Valley, Broder conceived of the notion of a magic cactus that people could split open and enter to see sick, dead, or dying loved ones; this concept became the premise of her latest book. In Death Valley, the narrator, also an author, finds herself in that same desert as she looks to crack her next novel; meanwhile, her father drifts in and out of consciousness at a Los Angeles hospital, her husband bedridden at home.

The similarities between Broder and Death Valley’s narrator run the gamut. Both identify as queer women, sharing a particular attraction to young-looking men and corpulent women (an authorial sexual preference reflected through The Pisces’s Theo and Milkfed’s Miriam as well). Both have an older husband with a mysterious illness that keeps him house-bound for months at a time. (If you’re interested, Broder wrote about her open relationship with her husband as part of her non-fiction essay collection, So Sad Today, and you can read that particular piece here.) Both suffered so-called “democracy injuries,” hurting their ankles en route home from the polls, and hold strong opinions about peeing as an underrated plot point in fiction.

I tend to find overly autobiographical analyses of fiction tangential to the point; every author uses their life as inspiration, the extent of its influence on their work operating as the only variable. In the case of Death Valley, however, my issues with the novel stem from its structural diversion at the halfway mark, something that seems to harken back to this near collapse between Broder and her latest narrator.

“A 100 percent Broder take on grief and empathy,” as Kirkus Reviews put it, the book begins with the narrator checking into a Best Western to commune with the California desert. As per usual, Broder’s style “mixes therapy-adjacent hyper-self-awareness, dark humor, and a jovially narcissistic approach to tragedy (‘I am still the kind of the person who makes another person’s coma all about me.’).” Each morning, the narrator deals with some sort of snafu tying to the hotel chain’s grab-and-go breakfast bags, a daily comedy routine punctuated by her dual attraction to the two front desk attendants, Jethra, an Eastern European woman with a “voluptuous belly,” and Zip, a “young man…who is “very much [her] other type.” Her exploration of the surrounding land leads to the magic cactus’s discovery, opening up opportunities to commune with younger versions of her father and husband.

Just as the narrator’s excursions start to hit a stride, she checks out of the hotel with plans to return to Los Angeles, ones that go awry when she gets lost in the desert. During her talk at The Center for Fiction, Broder revealed a less prolonged personal diversion in Death Valley with no water, no cell service. Her imagination spiraled and sense of time warped, leading her to wonder if she’d been gone for hours or mere minutes. The narrator’s journey in the back half of Death Valley follows a similar flow, an answer to the question of what would have happened had Broder’s own journey stretched over 18 hours instead of 18 minutes, and, from my perspective, lags as a result. The Back to the Future-esque poignancy of the cactus, the screwball sex comedy at the Best Western, become supplanted by page after page quippy survivalist fiction, a magic-infused Eat, Pray, Love for 2015-era Twitter enthusiasts.

Penance by Eliza Clark (2023) — Wow, I cannot stop thinking about this novel. In Cold Blood meets The Girls meets The Craft for the Tumblr generation, Penance takes the form of a true crime pastiche. It opens with the following disclaimer around “Penance,” a non-fiction exploration of the murder of 16-year-old Joni Wilson in coastal British town Crow-on-Sea written by disgraced tabloid journalist Alec Z. Carelli: “Shortly after publication, several of Carelli’s interviewees publicly accused Carelli of misrepresenting and even fabricating some of the content of their interviews. Following these accusations, it was discovered that therapeutic writing produced by two of the three offenders while incarcerated was illegally acquired by Carelli. The book was pulled from shelves by the original publisher in September of 2022…We believe writers (even writers of non-fiction) have a right to express themselves and tell stories in the manner they feel best fits the story in question…Despite the controversy attached to this book, we have chosen to republish it in its original form.” This framing device begs the question of narrator reliability from the outset, establishing a blurred binary between factual and emotional truth.

Told through excerpts from blogs, podcasts, and interviews, as well Carelli’s research and imaginings of how certain moments might have played out a la In Cold Blood, Penance expertly mimics what The Economist calls the “pioneering true crime tale” to critique the genre and its ethics. The novel opens with a retelling of the murder, the perpetrators’ identities initially anonymized: On June 23, 2016, the date of the Brexit referendum, three of Joni’s teenage classmates — Girl A, Girl B, and Girl C — kidnapped her and took her to an abandoned beach chalet, where they tortured her, then burned her alive. In the pages that follow, we learn the identities of the three girls — Girl A: popular-but-not-especially-well-liked bully Angelica Stirling-Stewart, Girl B: shy and passive Violet Hubbard, and Girl C: troubled ringleader Dolly Hart. In succession, Carelli teases out their relationships to Joni and each other, revealing the factors that led to this permanent act of violence; concurrently, per Dazed, “through the machinations of her unreliable narrator and the ever-shifting accounts of the girls themselves, Clark weaves a gripping tale that leads readers through podcast transcripts, text messages, interviews and Tumblr posts to show how stories become truth and explore the fraught space of teenage friendships and fandom as they collide with true crime.”

As someone easily bored by linear narratives, I found myself especially taken with the book’s formally inventive structure. Kirkus Reviews (unfairly IMO) slammed this aspect, stating: “The execution of this long, often tedious novel is not strong enough to support its ideas; instead, it reads like just another grisly story of a murdered girl. Great investigative nonfiction authors write novelistic prose, while Clark’s is clunky by comparison. The structure of her novel is similarly uninspiring, moving from one long interview to the next with little analysis.” I would argue that this reviewer missed the point. Clark establishes Carelli as a disgraced tabloid journalist, not a “great investigative nonfiction author.” Her ability to mimic a mid-tier Capote wannabe voice while building an immersive world, from my perspective, speaks to her abilities as an author. Moreover, as The New York Times notes: “In Crow-on-Sea, there are walking tours exploring grisly spectacles in the town that date back to the Vikings.” Clark’s attention to Crow — its folklore, its class dynamics, its history of violence — makes the small, seaside town and its inhabitants feel tangible; this specificity of setting culminates in a sense of realism that, for me, proved more engrossing than any interview analyses would have.

Penance also distills the cultural zeitgeist of the 2010s internet, zeroing in on early-days Tumblr. Each girl is uniquely, chronically online. A Glee and Andrew Lloyd Webber stan, Angelica looks to anons for validation. Violet runs a popular account dedicated to recounting some of Crow’s creepier town lore. Dolly stays active in school shooter fandoms, using fan fiction to process her own trauma. The specificity of these details capture a particular moment in time, while the girls’ broader dynamics with Joni, their peers, and each other coalesce to create a timeless portrait of teen girlhood taken to its worst extreme.

(Two important side notes: First, here’s a picture of Clark’s cat with a copy the novel. Second, Clark cites the incredibly wild and disturbing murder of Shanda Sharer from 1992 as an inspiration for Joni’s fate in Penance; you can read about it here.)

Her Body and Other Parties by Carmen Maria Machado (2017) — This collection masterfully embeds the violent into the banal (“After I hang up with her, I try to take a grapefruit apart with my hands, but it’s an impossible task. The skin clings to the fruit…eventually, I take a knife and lop off domes of rinds and cut the grapefruit into a cube before ripping it open with my fingers. It feels like I am dismantling a human heart.”) A queer Latina successor to the mid-century queen of horror, Carmen Maria Machado won the 2017 Shirley Jackson Award for Her Body and Other Parties for a reason. Per Kirkus Reviews, “Machado’s debut collection brings together eight stories that showcase her fluency in the bizarre, magical, and sharply frightening depths of the imagination. Each of the stories in this collection has, at its center, a strange and surprising idea that communicates, in a shockingly visceral way, the experience of living inside a woman's body.”

While objectively wonderful, this collection was, by and large, simply not for me. The stories that resonated really resonated. Others — for instance, “Especially Heinous,” a glorified creepy crawly Law & Order SVU fan fiction — really didn’t. “The Husband Stitch,” which I discussed in the October newsletter after reading it for my class at The Center for Fiction, remained my favorite. As a refresher: “This story, which ran in Granta in 2014, serves as Carmen Maria Machado’s twist on the tale of the green ribbon, an urban legend with origins threading back to Washington Irving’s 1824 short story, ‘The Adventure of the German Student.’ Predicated on the notion of a woman who constantly wears a collar or ribbon, provoking a man’s persistent curiosity, this horror trope has played out across short stories ranging from ‘The Velvet Ribbon,’ included in Ghostly Fun (1970) by Ann McGovern, to ‘The Green Ribbon,’ part of In a Dark, Dark Room and Other Scary Stories (1984) by Alvin Schwartz.” I also really enjoyed “Eight Bites,” Machado’s fantastical dissection of eating disorders, of how women relate to their bodies.

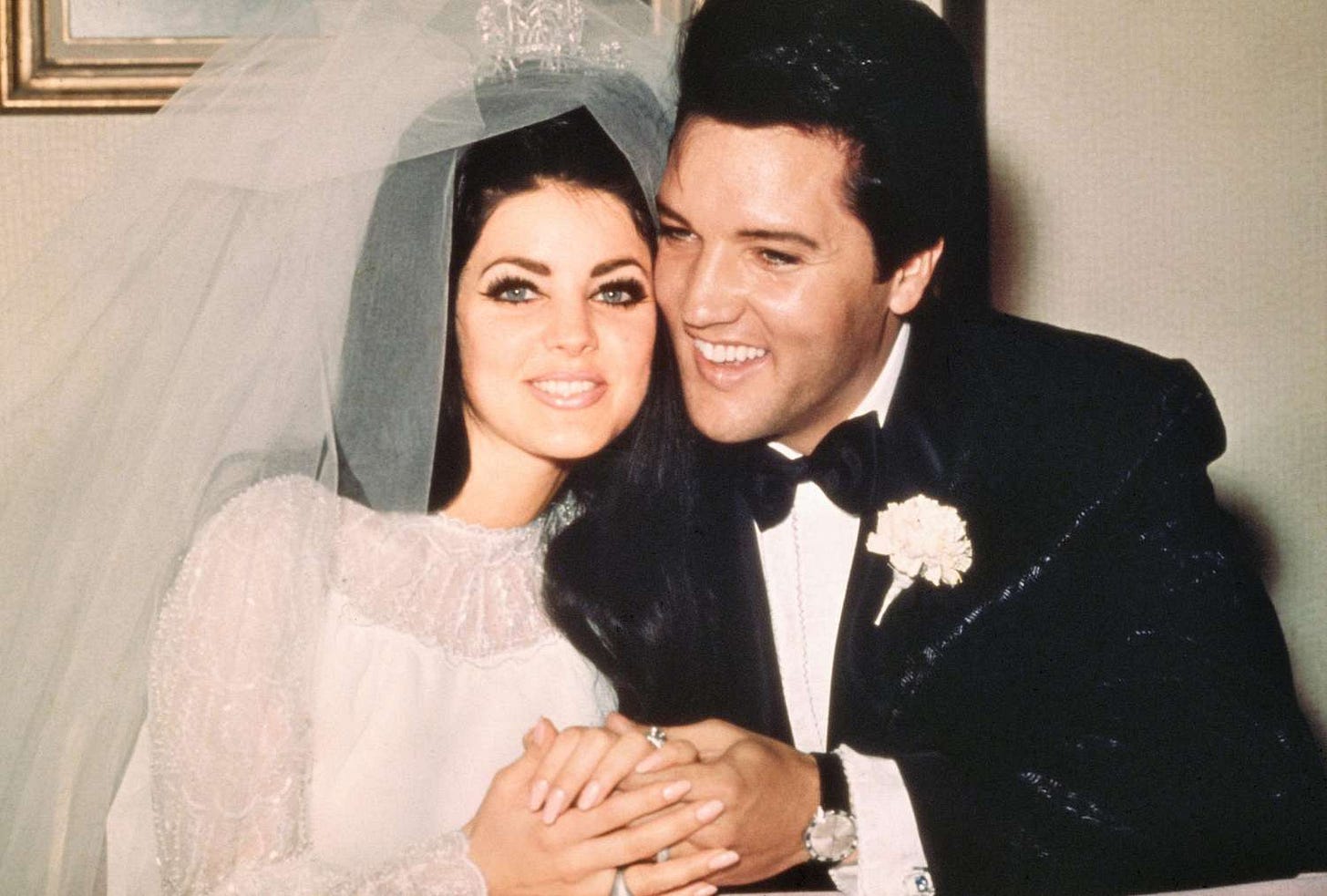

Elvis and Me by Priscilla Beaulieu Presley (1985) — Don’t Worry Darling (Priscilla’s Version)

October movie reviews will drop on the 2nd this month, but, in the meantime, keep an eye out for the November newsletter tomorrow!

xo,

Najet