Movies of the Month: September [2023]

On Sidney Poitier, Sarah Michelle Gellar, and Edward Said // in my Whit Stillman era

This month started with a 90s horror classic and ended with Whit Stillman’s “doomed bourgeois in love trilogy.”

Without further ado:

I Know What You Did Last Summer (1997, dir. Jim Gillespie) — Simply put, I’m not a horror movie girlie and haven’t been ever since my cousin forced me to watch the first ten minutes of The Ring in 2004, which lived in my nightmares rent free until about 2007. Scream, which I’ve seen too many times to count, serves as a primary exception. So, when I saw I Know What You Did Last Summer, penned by Kevin Williamson (aka: the mastermind behind the power trio of Scream, Dawson’s Creek, and The Vampire Diaries), included in The Criterion Channel’s High School Horror collection, I knew I had to watch.

The film follows four friends starting the summer after their senior year: Rory Gilmore dupe Julie James (played by Jennifer Love Hewitt), iconic pageant queen Helen Shivers (played by Sarah Michelle Gellar), entitled quarterback Barry Cox (played by Ryan Phillippe), and soft-spoken straight man Ray Bronson (played by Freddie Prinze Jr.). (Yes, Prinze and Gellar first met filming this movie, but, in it, are paired with Hewitt and Phillippe, respectively, which feels disorienting given the contemporary hindsight of their 20+-year marriage, but I digress.) After an accidental drunk driving hit-and-run on Fourth of July, the group disposes of a dead body off the coast of their sleepy North Carolina town and seemingly gets away with murder — until that night comes back to haunt them a year later, an analogue Pretty Little Liars.

This cult classic premiered the year after Scream became a sleeper hit and initiated the late 90s-to-early-2000s horror renaissance that famously ended the late 80s-to-early-90s lull. ICYMI, a horror history lesson: after the popularity of films like Halloween (1978), Friday the 13th (1980), and Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), the genre descended into poorly made ripoffs, relying on overused conventions that left audiences unsurprised until Scream’s self-awareness revitalized the genre’s popularity on a mass scale. Williamson’s involvement across the two films, coupled with the timing of their premieres, has, naturally, led to comparisons. But, while Scream delivers its kills with a wink and a nod, I Know What You Did Last Summer plays it straight, leaning into the tropes Scream mocks with an unspoken awareness its predecessors — due to the very nature of them being predecessors — unavoidably lack.

Reviewing the movie back in 1997, film critic James Berardinelli wrote: “There is one minor aspect of the plot that elevates I Know What You Did Last Summer above the level of a typical '80s slasher flick — it has an interesting subtext. I'm referring to the way the lives and friendships of these four individuals crumble in the wake of their accident. Guilt, confusion, and doubt build in them until they can no longer stand to be with each other or look at themselves in the mirror.” This narrative choice imbues the teens of I Know What You Did Last Summer with a certain level of depth that defies classic horror conventions.

Gellar, in particular, crafts a nuanced portrayal of Helen, who begins the film with aspirations of moving to New York to become an actress and, by its halfway mark, finds herself working retail in her family’s store. Her infamous chase scene with the killer has generated standalone think pieces, but, to me, a quieter moment stands out. Parked outside her house, Helen turns to Julie and says: “What happened between us? We used to be best friends.” Julie, emotionless, staring straight ahead, replies with: “We used to be a lot of things.” A tearful Helen voices that she misses Julie, who keeps her focus beyond the steering wheel. Registering the silence, Helen says, “Yeah…well,” then steps out of the car and toward her house. This scene, to me, captures the core of Berardinelli’s observation. It distills the essence of how trauma can crack friendships, how it feels when a former friend becomes a ghost.

Where to Watch: Hulu (premium subscription)

The Goonies (1985, dir. Richard Donner) — I had the pleasure of revisiting Steven Spielberg childhood classic at Cinespia over Labor Day weekend and realized it’s highkey about about gentrification. Anyway, a great cozy 80s rewatch for fall.

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video ($3.99)

Paris Blues (1961, dir. Martin Ritt) — You might recall I mentioned this then-upcoming screening, part of Metrograph’s Also Starring... Diahann Carroll series, in the September issue. I had always wanted to see this film, and it exceeded my expectations. Clever, entertaining, and genuinely funny, it captures a particular place (Paris), a certain sociopolitical moment, with glamour and glitz. Paul Newman and Sidney Poitier star as Ram Bowen and Eddie Cook, respectively, a pair of expat jazz musicians whose lives become complicated when American tourists Connie Lampson (played by Carroll) and Lillian Corning (played by Joanne Woodward) arrive on the scene.

First and foremost, Paris Blues is a vibe. Newman is ridiculously sexy and charming (even more so than usual). The bromance between his and Poitier’s characters is the quintessence of cool. On-location filming occurred, leading to gorgeous black-and-white shots of the city, streets buzzing with lights and people. Duke Ellington and Billy Strayhorn composed the score, while Louis Armstrong and real-life jazz pianist Aaron Bridgers have roles in the film, playing alongside Ram and Eddie during one particularly raucous club scene. A poster of Armstrong as his character, "Wild Man" Moore, appears in the train station during the opening scene, while its removal bookends the film. Armstrong delivers a powerhouse performance, and his presence in and of itself serves as a kind of shorthand, instilling the audience with immediate insight into the professional world Ram and Eddie occupy.

The Paris Review ran a piece on this film last summer. In it, novelist Darryl Pinckney writes, “The tension of the film is in whether the men will give up on their lives in Paris and go home with the women. In his study Blacks in Films (1975), Jim Pines argues that Ritt uses racial understatement as a form of alternate characterization. The racial theme is secondary to his purpose; his focus is on the struggle of the characters to maintain their individuality and integrity.” Eddie’s choice between Connie and his home, Ram’s between Lillian and his artistry, comprise the film’s core tension.

In his 1972 book, No Name in the Street, James Baldwin reflects on his experience as a Black American man in Paris and, within that, the stratification between North African immigrants and French natives across the city. He writes: “Every once in a while someone might be made uneasy by the color of my skin, or an expression on my face, or I might say something to make him uneasy, or I might, arbitrarily (there was no reason to suppose that they want me), claim kinship with the Arabs. Then, I was told with a generous smile, that I was different: le noir Americain est très évolvé, vayons! But the Arabs were not like me, they were not ‘civilized’ like me. It was something of a shock to hear myself described as civilized, but the accolade thirsted for so long had, alas, been delivered too late.”

Paris Blues teases out this breach between the United States’s and France’s treatment of Black people through the lens of Eddie and Connie’s relationship. The pair holds two different perspectives on how to respond to racism in the United States. Eddie chooses to build his life in France, a country where he feels safe and respected, explaining: “Sit down for lunch somewhere without getting clubbed for it and you'll wake up one day, look across the ocean and you'll say, ‘Who needs it?’” Meanwhile, Connie holds firm in her position that Black Americans have an obligation to stay in America to drive systemic change. For Connie, home is where you’re from; for Eddie, it’s where you’re wanted.

Ram takes interest in Connie toward the start of the film, but soon shifts his attention to Lillian; the two pair off for the remainder, leaving Eddie and Connie to do the same. The 1957 novel focuses on interracial romances, as did the first draft of the screenplay, but United Artists demanded that aspect get changed to satisfy a pre-Loving v. Virginia American audience. Aram Goudsouzian’s 2004 biography of Poitier, Sidney Poitier: Man, Actor, Icon, quotes him as saying: “Cold feet maneuvered to have it twisted around — lining up the colored guy with the colored girl.” Poitier goes on to reveal that, for him, the removal of that interracial aspect killed the film’s spark.

I agree that blurring the racial lines would have imbued the story with more charge. But, for me, the chemistry between the two couples — especially Newman and Woodward, who famously spent 50 years married in real life — worked well enough to overcome any narrative shortcomings. Without spoiling specifics, Lillian delivers a monologue toward the film’s end that I would rank amongst cinema’s most memorable, due in large part to Woodward’s delivery and palpable connection to Newman.

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video (premium subscription), The Roku Channel (free), Tubi (free), YouTube (linked here)

The Last Days of Disco (1998, dir. Whit Stillman) — RIP, F. Scott Fitzgerald. You would have loved The Last Days of Disco. This film follows a group of newly minted Manhattanites, recent Harvard and Hampshire graduates — including bookish heroine Alice (played by Chloe Sevigny), stylish sociopath Charlotte (played by Kate Beckinsale), desperate ad agency flunkie Jimmy (Mackenzie Astin), "nice guy” assistant district attorney Josh (played by Matt Keeslar), and womanizing club manager Des (played by Chris Eigman, aka: Jason Stiles from Gilmore Girls) — who fall in and out of love and friendship during — you guessed it — the last days of disco.

Much like Paris Blues, The Last Days of Disco is once again, first and foremost, a vibe. The soundtrack dips between disco classics like Alicia Bridges’s “I Love the Nightlife,” Cheryl Lynn’s “Got to be Real,” and Diana Ross’s “I’m Coming Out,” capturing the background noise of a bygone era. The film’s fictional club appears strikingly similar to archival images of Studio 54, an aesthetic molded partially from writer and director Whit Stillman’s memories of the stumbling into the space at 2:00 AM after getting off his early-days job at a New York newspaper. He told Dazed in 2016: “We set the film a little later than prime-time disco. I didn’t like the idea of disco as this sort of bad-taste, polyester version…I saw that at the beginning of the 80s, I really liked how things looked.”

But the film’s strongest point, among its many, lies in its dialogue. As Roger Ebert famously put it in his 1998 review of the film: “If Scott Fitzgerald were to return to life, he would feel at home in a Whit Stillman movie. Stillman listens to how people talk, and knows what it reveals about them.” A master of wit, Stillman captures the quintessence of what it means to be a postgrad professional in Manhattan, an experience simultaneously changed and unchanged over the course of four decades. His dialogue embodies the patterns of speech that defined the era, while also zeroing in on the timeless juxtaposition of knowledge and inexperience that tends to distinguish this particular demographic. In a 2009 Criterion essay on the film, screenwriter David Schickler observed: “We delight in their straight-faced, discursive tête-à-têtes about weighty topics like “The Tortoise and the Hare” or Lady and the Tramp or Scrooge McDuck because Stillman’s leading lords and ladies are all so damn (thank you, Mr. Wilde) earnest.”

Kate Beckinsale’s Charlotte most acutely embodies these contradictions. Stillman told The Guardian: “I had this idea for this over-the-top character, a kind of world-beater…Charlotte is very much a Jane Austen character.” Vanity Fair film critic K. Austin Collins adds: “Beckinsale plays her as a cool-tongued, uncannily deceptive socialite who doles out heaps of unasked-for advice in the form of cockamamie aphorisms, as if she’s styled herself after the know-it-all narrators of 18th-century novels, but without the advantage of those fictional society-types’ outright wit and intelligence.” Her academic pedigree, real-world stupidity, and blind self-assuredness coalesce to create someone chillingly lifelike.

The dynamic between Charlotte and Alice emerged as one of the film’s most compelling aspects for me. Charlotte dictates what Alice should say, how she should act, high on the act of doling out advice, on the power of asserting her superiority. An overt narcissist, Charlotte exhibits no remorse, no consideration for her friend’s best interest; at one point, she tells Alice (after deeply screwing her over): “Anything I did that was wrong, I apologize for. But anything I did that was not wrong, I don’t apologize for.” Charlotte repeatedly sets Alice up for failure, and Alice walks into the trap each time, her naive passivity as pronounced as Charlotte’s manipulative aggression. The pair embody a specific flavor of early twenties female frenemyship, one predicated on a boundary-less blend of sabotage and forgiveness that typically tends to have an expiration date.

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video ($3.99)

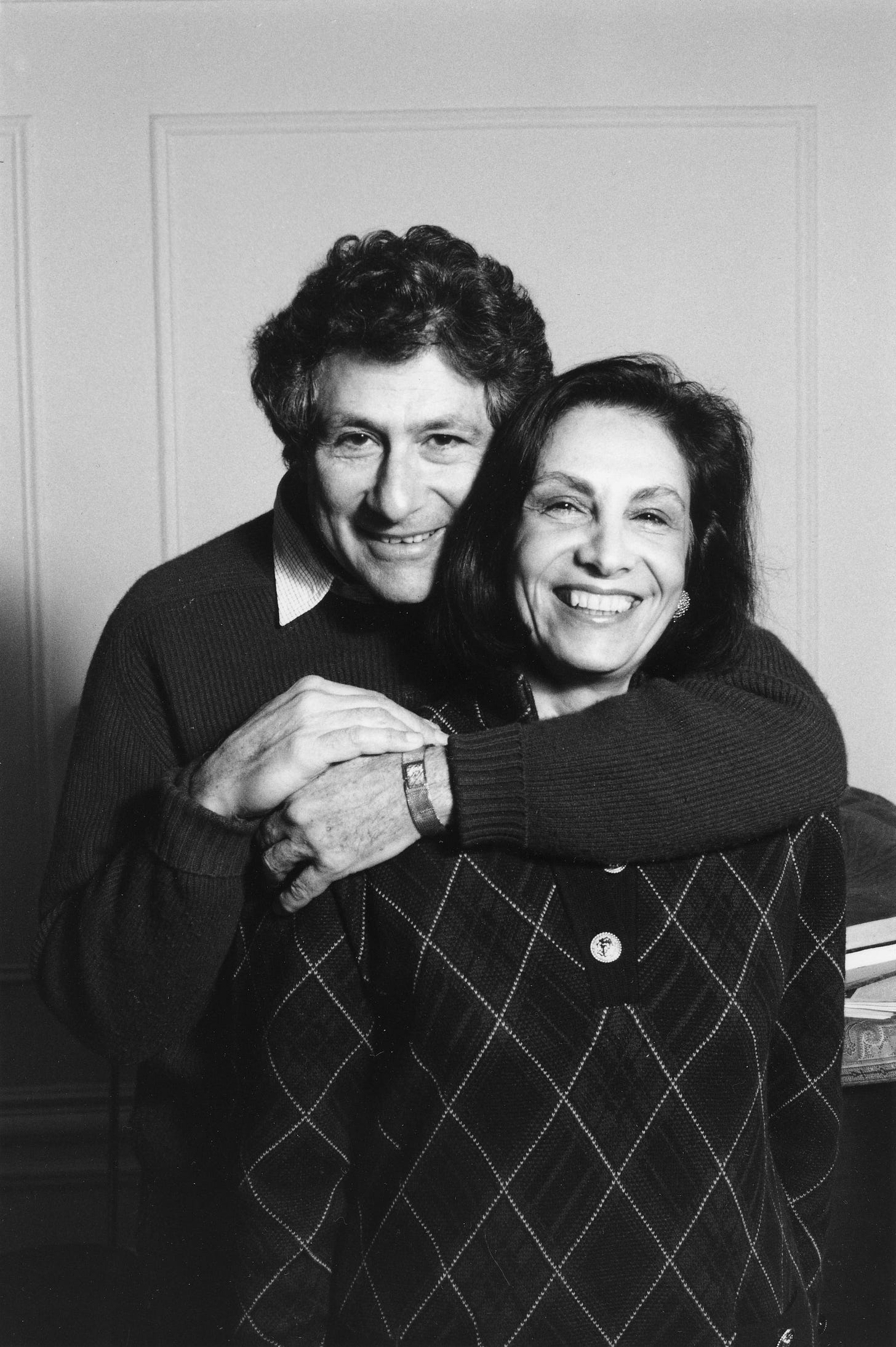

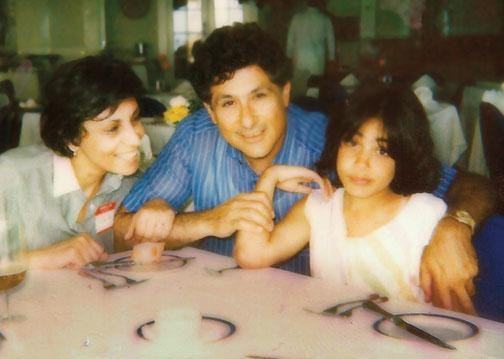

Selves and Others: A Portrait of Edward Said (2003, dir. Emmanuel Hamon) — I had the pleasure of seeing this intimate documentary at Film Forum as part of a special screening to commemorate the twentieth anniversary of Edward Said’s death. His widow, writer and activist Mariam Said, provided opening remarks. She framed the film as a kind of retrospective, a series of interviews with a man in the last leg of his life assessing his work, contemplating his legacy. The documentary filmed between fall of 2002 and spring of 2003, premiering in April. Edward Said passed away on September 25, 2003.

For those of you unfamiliar, Said was a Palestinian American public intellectual, literary critic, and activist. His 1978 book, Orientalism, became a backbone for studies of the Arab world, as well as the broader breach between concepts of Orient and Occident. He held a firm belief in the marriage between intellectual discourse and political action, a conviction he embodied throughout his life. Raised between Egypt and Palestine in the 1940s, Said immigrated to the United States to attend a Massachusetts boarding school at his parents’ behest in 1951. In the 1960s, Said stepped into an assistant professor position at Columbia University, where he taught until his death at age 67.

Selves and Others reveals Said the man as much as Said the thinker. The opening shot shows him driving through Hell’s Kitchen, discussing his eleven-year battle with leukemia. He expresses a desire to stay blind to his life expectancy, to focus only on the day before him. The camera frequently zeroes in on his hands as he speaks, as others speak, distilling the specificity of his physicality. Music plays a predominant role in the documentary as well; Said adored classical music and became a gifted, essentially concert-level pianist, a skill he showcases on film.

The multiplicity of identity that marked Said’s life serves as a driving force throughout the film; as a mixed race, white-passing Arab girlie, I felt incredibly seen by this layer of discourse. In Between Worlds, Reflections on Exile and Other Essays, Said writes: “With an unexceptionally Arab family name like ‘Saïd,’ connected to an improbably British first name...I was an uncomfortably anomalous student all through my early years: a Palestinian going to school in Egypt, with an English first name, an American passport, and no certain identity, at all.” The documentary echoes this notion as Said discusses how this ambiguity, despite its difficulties, allowed him the freedom to find connecting threads between multiple, seemingly contradictory ideas. He quotes Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” — “Do I contradict myself? / Very well then I contradict myself, / (I am large, I contain multitudes.)” — and advocates for a shift away from cleanly categorized singularity, toward an embrace of nuance.

Where to Watch: Not available on streaming at the moment, but keep an eye on Tubi and TCM’s film archive.

Metropolitan (1990, dir. Whit Stillman) — Gossip Girl (Whit Stillman’s Version)

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video (premium subscription), Max (subscription)

Keep an eye on your inbox for the October newsletter tomorrow and my review of Whit Stillman’s Barcelona (1994) to cap off the doomed bourgeois in love trilogy next month!

xo,

Najet