First things first, I saw so many new releases this month. Like, who is she?

Common denominators included my king, Jacob Elordi (simply need him in the upcoming adaptation of The Shards directed by Luca Guadagnino, especially after seeing Saltburn), Emerald Fennell, and Carey Mulligan.

Without further ado:

Priscilla (2023, dir. Sofia Coppola) — In Priscilla, writer and director Sofia Coppola brings Priscilla Presley’s 1985 memoir, Elvis and Me, which I discussed extensively last month, to life through the prism of candy-coated girlhood that defines some of her most seminal works, namely The Virgin Suicides (1999) and Marie Antoinette (2006). The movie opens with teenage Priscilla Beaulieu (played by Cailee Spaeny) living in Germany during her father’s deployment; doing her homework in a diner one day, she gets invited to a party at the home of Elvis Presley (played by Jacob Elordi). An immediate connection emerges between Elvis and Priscilla, with the film tracking their romance from inception to dissolution.

You already know what I’m going to say — this movie is, first and foremost, an absolute vibe. Coppola shoots certain sequences — from Elvis and Priscilla’s wedding to lazy days spent by the pool — between sepia and regular coloring. “Sleep Walk” by Santo & Johnny recurs in these moments, emerging as the anthem that inserts the audience into a kind of broken dream. A stylistic trademark, Coppola integrates anachronistic picks throughout the soundtrack to convey Priscilla’s emotional truth with precision. The opening credits blare The Ramones’s “Baby, I Love You” (my third most played song of 2023, per Spotify Wrapped) over a montage of Priscilla — in her trademark, early 60s style — getting ready for the day at Graceland. Tommy James and the Shondells’s “Crimson and Clover” plays as Priscilla lazily wanders through the hallway of her high school in Germany, dazed by her newfound romance. Elvis’s own music remains notably absent, a rights issue that, as I see it, works to Coppola’s creative advantage; “I Will Always Love You” scores the movie’s final moments, her selection of the Dolly Parton cover seemingly operating as a signifier of Priscilla’s liberation.

Early on, multiple scenes feature men brokering the specifics of Priscilla’s life without her input. Terry West (played by Luke Humphrey) invites her to Elvis’s house in Germany, subsequently negotiating with Priscilla’s father to bring the meeting to fruition. Her father, Elvis, and his father, Vernon (played by Tim Post), similarly mediate her visits and eventual move to Graceland; Coppola shows the meeting in partial view, with Priscilla and her mother (played by Dagmara Dominczyk) avidly eavesdropping from their kitchen. Once she arrives at her new home, as Glenn Kenny succinctly summarizes in his review for RogerEbert.com: “A lot of the times Priscilla just doesn’t know what to do with herself.” Priscilla often appears wandering around Graceland either alone or accompanied by her dog, Honey, a gift from Elvis. In Coppola’s 2006 film, Marie Antoinette parts ways with her pug upon arrival at Versailles, a marker of childhood left behind; meanwhile, in Priscilla, Honey seems to signify its titular character’s perpetual youth and newfound isolation. Coppola, as always, captures and cultivates the aesthetic of youthful powerlessness and exquisite loneliness.

Color plays a predominant role in the film. In its first third, Priscilla frequently appears in pale pink, an apparent indicator of youth, of girlishness, of innocence, accentuated by her signature heart-shaped choker. In describing Priscilla’s first visit to Graceland, British journalist and film critic Anthony Lane, in his review for The New Yorker, writes: “Armed with a first-class ticket on Pan Am — and, for some unfathomable reason, the consent of her parents — Priscilla goes to visit him [Elvis], arriving at Graceland in a pink dress and white gloves. After a bacchanalian interlude in Las Vegas, there’s a wonderful shot of her returning to Germany, her clothes still immaculate but her hair and makeup in meltdown.” Coppola understands the decorative material of girlhood, the power minute objects — from heart-shaped jewelry to floral stationary — hold. These details fade upon Priscilla’s arrival at Graceland, her girlhood absorbed into pristine interiors, into the black leather den Elvis calls a bedroom as he slowly remakes her to fit his desired image.

Lane continues: “To point out that Priscilla is superficial, even more so than Coppola’s other films, is no derogation, because surfaces are her subject. She examines the skin of the observable world without presuming to seek the flesh beneath, and this latest work is an agglomeration of things — purchases, ornaments, and textures.” A scene pulled almost directly from Elvis and Me shows Priscilla modeling different dress options for Elvis and his entourage, cueing a running commentary that continues to shape her look (“As I tried on dress after dress, Elvis delivered a running commentary on color. He liked me in red, blue, turquoise, emerald green, and black and white — the same colors he himself wore. He liked solids only, declaring that large prints took away from my looks. ‘Too distracting,’ he said. He hated browns and dark green, colors inextricably associated in his mind with the Army.”). Elvis’s preference for blue and distaste for patterns operates as an oppositional binary throughout the remainder of the film; in moments of empowerment, Priscilla appears in “large prints,” whereas blue comes to signify submission and isolation.

Elvis sets the mood and pacing of their relationship, drawing Priscilla into his world rather than building a new one alongside her; he maintains the power, while she has none. An early moment sets this tone. As Elvis prepares to return to the United States, Priscilla drives with him to the airport. Hordes of fans descend on their car, cropped female torsos and Elvis Presley posters visible through the back window. Before leaving, Elvis tells Priscilla he doesn’t want to see a sad face. Two recurring threads materialize here: the ill-timed emergence of an entourage, Elvis’s pursuit of the illusion of joy rather than the reality of it.

During his later travels, Priscilla invariably says she loves or misses him at the end of each phone call, receiving no response in return. He determines how and when they engage sexually, repeatedly rebuffing her advances and advocating for chastity despite pursuing other women (most famously Ann-Margret on the set of Viva Las Vegas) in parallel. He molds Priscilla into his dream girl rather than giving her the space to shape her own identity. Upon leaving the theater, I heard a group of girlies critiquing Priscilla’s blankness; why didn’t she have more of a personality? From my perspective — perhaps a perspective shaped by having read the memoir in advance —, that blankness, its slow erosion, is the point.

At his behest, Elvis and Priscilla have an audience for everything, even moments as intimate as her pregnancy announcement. When Priscilla goes into labor, she gets ready for the hospital alone, methodically applying her Elvis-approved makeup, her signature false eyelashes. Muffled noise scores the moment, the sound of Elvis alerting his entourage of Lisa Marie’s impending arrival. The ending powerfully inverts this pattern. In Vegas, Priscilla dines with three friends while Elvis remains in his room, occupying the state of exquisite loneliness his wife has abandoned. As Kenny describes: “His tragedy becomes Priscilla’s liberation. And so Coppola’s movie resolves on notes both poignant and haunting.”

From my perspective, Cailee Spaeny and Jacob Elordi do a phenomenal job of capturing Priscilla and Elvis’s hypnotic relationship. Per Kenny: “The 25-year-old [Spaeny] plays 14 so damn well that the viewer almost doubts that she’ll be able to credibly age into a woman nearing 30. But she does, beautifully. As Elvis, Jacob Elordi towers over her; the contrast is an exaggeration from real-life but an effective one. This Elvis is soft-spoken, given to discomfiting bursts of anger as he comes to rely more and more on medications to boost energy and get to sleep; all the stuff that killed the man, in the end, is here in ostensibly more manageable form, but Coppola’s storytelling does convey its insidious creep.”

Perpetual youth — and the cost of clinging to it — marks their relationship. As Lane so aptly puts it: “What’s clear is that he [Elvis], no less than Priscilla, is something of a kid; while denying her the comfort of any friends, he is encircled by a rowdy rat pack of pals, who cheer as the King knocks down a house for fun.” In a stunning piece for NYRB, CUNY PHD Student Zoe Hu characterizes the film as a meditation on the danger of child’s play, of Elvis and Priscilla’s relationship as one undertaken between two kids who, inevitably, grow up. She observes: “Through Coppola, we watch her [Priscilla] leave her relationship and move away from Graceland. We never see her after this separation, which inaugurates the rest of her life. This pivot on Coppola’s part is interesting: here is a film that treats solitude rather than marriage as the fairytale ending that, like all fairytale endings, cannot be elaborated upon.”

Where to Watch: ~a theatre near you~

Promising Young Woman (2020, dir. Emerald Fennell) — I know I’m late to the party here, but what a film. I watched this one before seeing Saltburn (more on that in a minute) and found myself absolutely blown away by Emerald Fennell’s script, Carey Mulligan’s performance, and the opening sequence’s ability to make me distrust Adam Brody.

ICYMI: The Me Too-era thriller follows 30-year-old med school dropout Cassie Thomas (played by Carey Mulligan) as she looks to avenge the rape of her dead best friend, Nina Fisher. Night after night, Cassie plays drunk, goes home with Nice Guys™, and then, on the brink of getting taken advantage of, makes her sobriety known to teach them a lesson. She works at a local coffee shop and lives with her parents, for whom the ghost of her potential serves as a stifling force. The monotony of Cassie’s routine marches on until she reconnects with former med school classmate Ryan Cooper (played by Bo Burnham). He reveals the impending wedding of Nina’s rapist, Alexander Monroe (played by Chris Lowell), prompting Cassie to pursue a more targeted, sophisticated vengeance scheme.

Writer and director Emerald Fennell (aka: Camilla in seasons three and four of The Crown) builds a layered aesthetic, one that reflects the multiplicity of Cassie’s personality. Per IndieWire: “In order to explain that dichotomy between Cassie — the lollipop-sucking sweet-shop worker with a massive affection for the dulcet tones of Paris Hilton and Britney Spears, but also the wily revenge-seeker who carries a notebook filled with the names of her “victims” — Fennell crafted mood boards. They included all sorts of shiny reference points, from ’60s French films to Sweet Valley High books, a multicolored manicure, bright clothing, all the better to sell the soft sweetness of Cassie, before flipping it into far darker territory.” Mulligan’s performance further underscores this dichotomy, as she seamlessly switches between candy coated ingenue to no holds barred ball-breaker.

If you’ve followed this Substack for a while, you know I have a lot of feelings about the value of showing versus telling in literary fiction (see: my review of Remarkably Bright Creatures by Shelby Van Pelt from August). But, in film, I tend to focus on aesthetics over text, probably thanks to my random Art History degree. In the case of Promising Young Woman, however, I found myself predominantly fixated on the novelistic nature of the Academy Award-winning script. Fennell inserts the audience into Cassie’s story, then allows them to pick up the broader context through visual cues and conversations. By resisting the temptation to insert Sex and the City season one-style asides or unrealistically expository dialogue, Fennell cultivates a penetrating sense of immediacy.

**spoilers ahead for Promising Young Woman and also In the Cut by Susanna Moore*

For instance, Cassie eventually gets a hold of and watches a video depicting Nina’s brutal rape. A lesser filmmaker would have shown the video to the audience, but Fennell instead chooses subtext. We hear the voices of the boys in the room, see a close crop of Cassie’s face. Mulligan’s performance — widely and justifiably cited as a career best in this film — shines in this moment. Fennell then implements a wide, fisheye-like shot (pictured above) as Cassie runs out of her home, one that seems to invite the audience to process her loneliness, wallow in her heartbreak. The revelations contained in the video remain a mystery until the following scene, further fueling that sense of suspense.

The film’s final act struck me as eerily reminiscent of In the Cut, a 1995 erotica thriller by Susanna Moore. In it, as I wrote when reviewing the novel back in August, “Frannie Avery, an NYU English teacher studying street vernacular for her upcoming book…stumbles upon a redhead giving a tattooed mystery man a blowjob in the back of a Greenwich Village bar. When said redhead turns up dead, Frannie finds herself at the investigation’s center. Moore crafts a nuanced thriller that explores the thin line between sex and violence, as well as the casual racism of the NYPD, against the backdrop of Giuliani-era New York.” Frannie’s life hangs in the balance throughout the course of the novel, but the fact of her narration seems to assure survival. The final pages, however, call that presumption into question. Fennell implements a similar tactic in Promising Young Woman; close adherence to Cassie’s perspective throughout the bulk of the film seems to render her invincible — until it doesn’t.

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video (Premium Subscription; allegedly free with ads, but I did not see a single ad)

Saltburn (2023, dir. Emerald Fennell) — Big month for my crush on Jacob Elordi. As I headed to The Angelika to see this film, my friend (shout out Courtney, who doesn’t follow this Substack) texted me saying, “the first 30 mins is really just an ad for jacob elordi being the hottest man i’ve ever seen,” and she was correct. But I digress. An early aughts-set Brideshead Revisited meets The Talented Mr. Ripley, Saltburn, to me, felt like it could have been a cross-collaboration between Donna Tartt and Bret Easton Ellis by way of Oscar Wilde and the masterminds between the outfits on The Simple Life. So, naturally, I ate it up.

The second feature film from writer and director Emerald Fennell, Saltburn opens with scholarship student Oliver Quick (played by Barry Keoghan) arriving at Oxford. A fish out of water amidst a sea of students steeped in intergenerational wealth, Oliver remains somewhat isolated until finding a friend in wealthy, popular, but ultimately good-hearted Felix Catton (played by Jacob Elordi). After Oliver opens up about his rough home life, Felix invites him to stay at his family’s estate, Saltburn, for the summer alongside his father, Sir James (played by Richard E. Grant); madcap mother Lady Elsbeth (played by the brilliant Rosamund Pike, who delivers Elsbeth’s scathing monologues and one-liners with a delicious bite); troubled sister Venetia (played brilliantly by Conversations with Friends’s Alison Oliver); and snarky cousin and fellow classmate of theirs, Farleigh Start (played by Archie Madekwe). But what starts out as a homoerotic, madcap dip into the emotional repression, verbal gymnastics, and excessive wealth of British high society soon takes a dark turn.

After watching Promising Young Woman (2020) and Saltburn back to back, I found myself especially struck by the evolution of Fennell’s style as a filmmaker; it felt almost like reading a novelist’s debut, a high-quality one that still lacks a tonally distinctive style, followed by a more fulsome second act. In discussing his 1985 debut, Less Than Zero, my problematic parasocial bestie Bret frequently mentions his fixation with Joan Didion, his habit of studying her prose for hours on end and looking to replicate it as a means of capturing “numbness as a feeling.” His latest novel, The Shards, which I’m legally obligated to mention in every newsletter, marks a sharp diversion from that initial pursuit, embracing an emotional flavor of prose rarely found in his earlier works, in turn pioneering a distinctive style that serves as the scaffolding for a vibier novel than its predecessors. Saltburn marks a similar kind of progression from Promising Young Woman.

Despite arguably offering a more solid narrative, Promising Young Woman lacks the distinctive aesthetic that Saltburn has in spades. Yes, the former included some beautiful shots clearly influenced by Fennell’s aforementioned practice of creating moodboards. But it largely felt indistinguishable from the scores of brightly lit Netflix original films that graced our screens in the 2010s. (Certain shots quite literally felt like direct lifts from the 2018 rom com masterpiece, Set It Up.) In her sophomore endeavor, however, Fennell seems to find her stylistic stride. In discussing the opening sequence, she explained: ““Zadok the Priest – composed for the coronation of George II – is [played at] the beginning of Saltburn because it feels like the absolute apex of Brexit Britain. Tea and scones, Oxford, Brideshead Revisited Britain. It’s got the thing that we export – the jingoistic stuff. So that was always the opening for my film, the idea of: here we are, good old England!” That selection, paired with looming shots of Oxford, creates an immediate sense of style that drops the audience into the world of the film, giving way to the cultivation of a vibe that carries through the two plus hours that follow.

A side note that continues to drive me nuts the more I think about it: the timeline. The opening sequence features posters that read “Welcome Class of 2006,” placing the film’s start in the fall of 2002 and the bulk of the action in the summer of 2003. Most reviewers, however, interpreted it as taking place in 2006 because of that sign (probably the result of seeing the year 2006 and simply registering it as being 2006, a totally valid misread). But pop cultural insertions, from a karaoke rendition of Flo Rida’s Low (first released in fall of 2007) to a sequence of the family watching Superbad (released in August of 2007), muddle the intended era. Oliver and Felix appear as freshmen, but, even if Fennell had intended it to chronicle their senior year, the film would have occurred in 2005 heading into the summer of 2006, and those cultural touchstones that pepper the summer sequence would still be a year — and, in some cases, a year plus — away. Based on interviews, it seems as though Fennell intended the film to take place in the the fall of 2006 heading into the summer of 2007 and simply didn’t pay attention to the details.

I don’t mind an anachronism if it feels intentional on the part of the filmmaker. Think of Sofia Coppola’s iconic usage of “What Ever Happened?” by The Strokes in Marie Antoinette (2006) or, more recently, The Ramones’s 1980s cover of The Ronnettes’s 1963 single, “Baby, I Love You” over the opening sequence of Priscilla, as discussed. One of Saltburn’s vibiest montages falls in this vein, featuring Oliver, Felix, Venetia, and Farleigh playing tennis and drinking champagne in formalwear while “Time To Pretend” by MGMT (first released in 2005, which would render it an anachronism against the 2002-2003 timeline that the welcome signs connote). As I’ve written previously, “vibes intersect with quality where style serves as scaffolding.” These song choices coalesce with the moments they score to create an aesthetic combination of audio and visual that gives way to style and, by extension, high-quality vibes. The Catton family enjoying a karaoke rendition of “Low” or a screening of Superbad, however, occurs in the world of the film rather than getting layered on top of it, creating confusion rather than contributing to the sense of style Fennell otherwise crafts.

Where to Watch: ~a theatre near you~

Party Girl (1995, dir. Daisy von Scherler Mayer) — A feel-good 80s movie for all the girlies who have ever had to adjust to the concept of having a job.

This cult classic dramedy follows stylish adult orphan Mary (played by it girl of the era Parker Posey) as she descends into the Dewey Decimal System-laden world of library science. After getting arrested for organizing an underground rave, she calls on her godmother, Judy (played by Sasha von Scherler), to bail her out. To repay the bail fee, Mary takes a job at the library where Judy works and, after smoking a well-timed joint, sets out to rectify her reputation as altogether unmotivated. In between all that, Mary flirts with her halal guy, Lebanese immigrant Mustafa (played by Omar Townsend), and wears fabulous, seemingly Fran Drescher-approved outfits.

Parker Posey’s Mary, to me, captures the quintessence of what it means to be 24 years old and have absolutely no idea what you’re doing aside from getting a falafel with hot sauce, a side order of Baba Ghanoush, and a seltzer. I also cannot overstate how fun the fashion is, how the film distills the texture of a specific time and place. I came across a Gen X blogger’s homage, in which she writes: “The costumes for this film were done by the wonderful Michael Clancy, who catalogued some of the looks and his sketches for them on his website. He used designers that were incredibly unique and edgy and of that time like the aforementioned Todd Oldham, Vivienne Westwood, and king of streetwear Jean Paul Gaultier.” She goes on: “Apart from the Gen Xer-ness of this movie, it is also a tribute to New York in the early 90s and the club culture there. It would be another four or five years before raves and rave style hit the mainstream, but this movie really documents that little community of underground clubs in Manhattan.”

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video (Premium Subscription)

Maestro (2023, dir. Bradley Cooper) — I went into this movie knowing virtually nothing about Leonard Bernstein except a) his status as arguably the most iconic American composer of his time and b) that Lauren Bacall used to party at his apartment in The Dakota during and after her marriage to Jason Robards. The film opens with a quote from Bernstein that reads: “A work of art does not answer questions; it provokes them; and its essential meaning is in the tension between the contradictory answers.” The remaining 129 minutes explore this theme through the multiplicity of identity that defined Bernstein, through a thoughtful portrait of his and actress Felicia Montealegre’s marriage

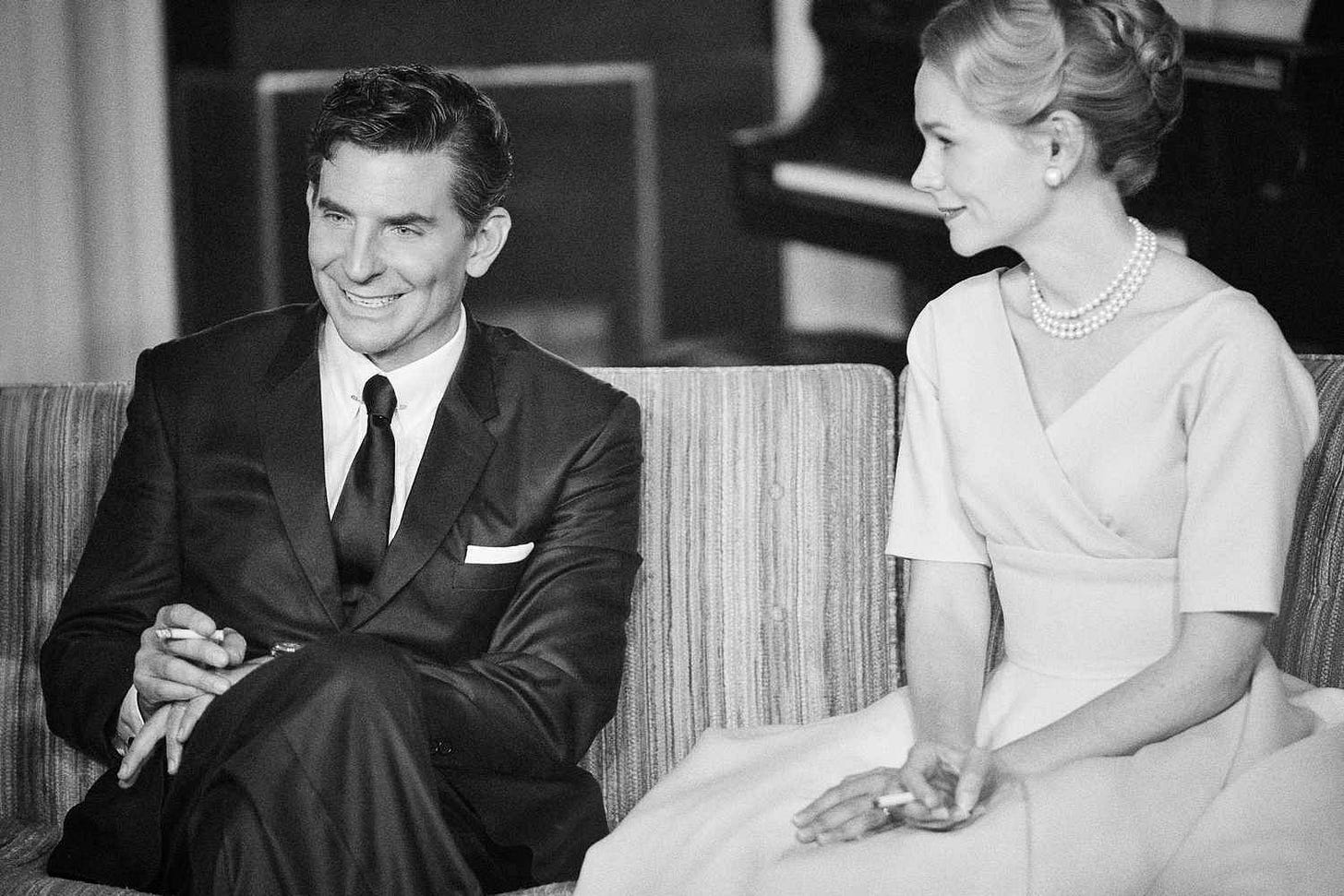

Maestro opens with Bernstein (played by Bradley Cooper, first introduced in old age makeup that’s loudly yelling for an Oscar) at the piano in the midst of an interview. Crafted as a kind of memory piece a la Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie, the film then jumps backward in time, from color to black and white. It traces the start of Bernstein’s career, his first meeting with Felicia (played by Carey Mulligan) in 1946, before propelling forward through the remainder of their life together and, on occasion, apart.

Scenes dreamily float from one to the next, especially in the film’s first act. Bradley Cooper told set designer Kevin Thompson that he wanted Maestro to move “seamlessly from decade to decade with a lyrical feeling,” describing his vision for the movie as “a piece of music…that you just sort of float through.” While Cooper certainly achieves that lyricism, the black-and-white scenes, to me, felt a bit gimmicky. The aesthetics evolve as the narrative unfolds through time, returning to color somewhere around the 1960s; this reintroduction, from my perspective, helps the film to take on on a more grounded, mature quality for its final two thirds.

Bradley Cooper and Carey Mulligan are so insanely good as “Lenny and Felicia.” I had the pleasure of seeing the first public screening at The Paris Theater the day before Thanksgiving, which included a Q&A with Mulligan after the film. During that discussion, she underscored the extent to which Cooper prepared for this part, the result of research that began around the film’s incept back in 2018. Cooper and Mulligan’s shared dedication to embodying and enlivening the couple carries through in the detailed physicality of their performances, in the specificity of their dialect. For instance, I recommend watching this Edward Morrow interview (despite its incredibly quiet audio) with Lenny and Felicia from 1955 and comparing it to the film’s recreation of the same scene; the difference, to me, feels nearly indistinguishable.

Beyond voices and mannerisms, Cooper and Mulligan capture the layered emotions behind Lenny and Felicia’s 27-year union. As The New Yorker put it: “Felicia is well aware, when she marries Bernstein, that he is bisexual; what she fails to foresee is how panamorous he is. ‘I love too much, what can I say?’ he declares, in proud and mirthful apology, and the movie surveys the blast area around his uncontainable person. He cannot stanch the joy of his desiring any more than he can curb the catholicity of his musical tastes, and, for good or ill, other souls feel the brunt.” The brimming multiplicity of Bernstein’s identity — and its impact on Felicia, on their family, for better and for worse — becomes one of the film’s driving forces. This tension bubbles most prominently to the surface during a fight between the couple on Thanksgiving in their Dakota apartment (which, for the record, Thompson and his set design team recreated in full on a soundstage). Shot from a distance in an elongated take, it feels like something out of the stage version of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?.

A good portion of the film takes place in Lenny and Felicia’s house in Fairfield, Connecticut (pictured above). Cooper worked closely with the Bernsteins’ three children throughout the production process, gaining permission to film those scenes inside the family home. The Bernstein children gifted Felicia’s old cigarette lighter to Mulligan, with it appearing from the 1960s — when she first received it as a gift in real life — onward. After unearthing an old dress of Felicia’s, they gave it the costuming department for Mulligan’s use. Toward the Q&A’s end, the interviewer asked Mulligan if she considered Lenny and Felicia’s marriage a success, a failure, or something in between. She noted that it held the good and the bad, like most things, but pointed to the Bernstein children — now in their 60s and 70s —, to their bond, as a testament to the power of their parents’ enduring companionship.

The New Yorker piece continues: “Strange to say, Maestro isn’t really about music…The whole thing may be drenched in music, but Cooper is inspired less by the creative source of the sound than by the emotional destination to which it flows—that is, Felicia.”

Where to Watch: ~a theatre near you~

Alright, that’s it! I am once again reminding you to stay tuned for a ~festive~ December newsletter tomorrow.

xo,

Najet