Hello, and welcome to the first issue of my Substack! As a wise friend of mine (hi, Joanna) once said, “I feel like 90% of your friendships are based on content recommendations.” So, here’s one big macro newsletter with all my content recommendations in one place!

At the top of each month, I’ll recap what I read, watched, etc. over the prior one and share recommendations on content for you to consume in the month ahead. So, without further ado:

A Look Back: July Book Review

Lunar Park by Bret Easton Ellis (2005) — If you know, you know Bret is my problematic fave with whom I’ve developed a borderline parasocial relationship after spending hours listening to The Bret Easton Ellis Podcast on Patreon. So, of course I loved this book. It tells the story of a fictionalized Bret Easton Ellis, one who settled down in Westchester with a wife and two kids. Developed as an homage to the work of Stephen King, the book functions as a ghost story that examines father-son relationships, the notion of haunting as both everyday and supernatural, and the inner workings of the mind of the writer. Set in 2003, it captures post-9/11 American suburbia to a tee, from elementary school obsessions with The Backstreet Boys and The Spice Girls to the golden era of Furbies.

Lunar Park strikes me as the most similar to Bret’s latest book The Shards, which quickly emerged as a personal favorite when I read it in February; both novels contain mysteries with similar markers or clues, taking on softer, more emotional tones than earlier books like Less Than Zero (1985) or The Rules of Attraction (1987), both designed to capture “numbness as a feeling.”

I suggest reading Lunar Park after the rest of Bret’s body of work; it’s filled with Easter eggs that will feel richer with that context. (Okay, okay, since you asked, probably — my recommended order for reading Bret’s work is: Less Than Zero, The Rules of Attraction, American Psycho (1991), The Shards (2023), The Informers (1994), Lunar Park (2005), and then Glamorama (1998) whenever you want because that book is LONG, and I still haven’t touched it.)

In the Cut by Susanna Moore (1995) — My favorite bookshop, Three Lives & Company in the West Village, has a book of the month program, wherein you receive a customized monthly book recommendation based on authors and books you’ve enjoyed in the past. I’ve been participating since my dear friend Mel (hi, Mel!) first got me a six-month subscription at the end of 2020 that I then continued on my own. I’ve come across some of my favorite authors (@Laurie Colwin) and books (Summerwater, The Travelers, Funny Weather, A Little Devil in America, Today a Women Went Mad in the Supermarket, Small Things Like These, On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint, The English Understand Wool, and, most recently, Good Morning, Midnight ~to name a few~) through Manager Troy Chatterton and his team. All that to say, In the Cut was my Three Lives book of the month for July.

The rare literary fiction novel with a commercial plot, In the Cut follows Frannie Avery, an NYU English teacher studying street vernacular for her upcoming book. In the opening scene, she stumbles upon a redhead giving a tattooed mystery man a blowjob in the back of a Greenwich Village bar. When said redhead turns up dead, Frannie finds herself at the investigation’s center. Moore crafts a nuanced thriller that explores the thin line between sex and violence, as well as the casual racism of the NYPD, against the backdrop of Giuliani-era New York. Frannie’s appreciation of and commentary on language shapes the world of the novel, sharpening the layers of class, race, and gender identities that delineate its cast of characters. It’s also a masterclass in writing sex, something incredibly difficult to do well.

Glossy: Ambition, Beauty, and the Insider Story of Emily Weiss’s Glossier by Marisa Meltzer (2023) — This upcoming exposé on the meteoric rise of Glossier and its elusive founder Emily Weiss serves as more than just a deep dive on a beauty brand. It captures the cultural zeitgeist of the 2010s, something I’ve been thinking about since I read Vanity Fair’s interview with Audrey Gelman on life after The Wing, in which the journalist observes how “hustle-culture sterility gave way to a slow era of cozy pandemic maximalism.” This line so aptly summarizes the “vibe shift” I — and The Cut — had been trying to pinpoint, the sharp drop-off between decades that the onset of the pandemic in March 2020 made all the more steep.

Meltzer — author, journalist, and famously a restorative instructor at my go-to yoga studio — identifies the cult of girlboss (read as: corporate white) feminism as the 2010s’ version of hero worshipping garage-dwelling tech founders in the 90s and Gordon Gekko-esque Wall Street bros in the 80s. This latest era, however, took a unique turn compared to its predecessors by conflating capitalism with a movement, sanitizing and selling a palatable strain of feminism until millennial pink and too-friendly fonts reached their shelf lives. Glossier emerged as the cool factor coalesced around the “female founder who also went to 6 a.m. yoga classes…wore a chic dress and looked coiffed on Instagram…was liberal and outspoken about her gender.” But the brand still sustained its chokehold on culture as “bimboism surged when the girlboss fell from grace,” thanks, in large part, to Weiss knowing her strengths as a creative and weaknesses as a leader, when to step up and when to step down.

The journalist-subject relationship between Meltzer and Weiss ebbs and flows against the narrative backdrop, coming into focus at key points, then fading out again until it dominates the final chapters. The book opens with Weiss in tears at the prospect of this very exposé hitting bookstores once she catches wind of its soapy subhead, bringing to mind the Janet Malcolm quote: “Every journalist who is not too stupid or full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible. He is a kind of confidence man, preying on people's vanity, ignorance, or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse.”

Recounting their final interview, Meltzer rolls her eyes at Weiss’s eternal optimism, rehearsed positivity, and overall guardedness. A certain incredulity bubbles around Weiss’s refusal to admit failure, to declare defeat, even as she resigns her CEO role. As a writer, I understand Meltzer’s disappointment, her desire for a juicier story. As a PR professional, I’m baffled; why would an executive whose guardedness cemented her as “the last girlboss standing” suddenly abandon it to treat a journalist — and a double crossing one, from Weiss’s perspective — like a trusted gal pal? For me, this grievance colors Meltzer’s closing characterization of Weiss as “a complicated woman who is admired more than she is liked” as somewhat personal, the byproduct of her own frustration rather than Weiss’s (very real) shortcomings as a leader.

But pick up a copy in September and decide for yourself. (Huge thank you to my friend Rebecca for the galley!)

Girl, Interrupted by Susanna Kaysen (1993) — In the opening pages of her memoir, Kaysen explains what it felt like to creep into madness, into a fabled Massachusetts mental institution, at age 18. She narrates: “It is easy to slip into a parallel universe. There are so many of them: worlds of the insane, the criminal, the crippled, the dying, perhaps the dead as well. These worlds exist alongside this world and resemble it, but are not in it…although it is invisible from this side, once you are in it you can easily see the world you came from. Every window on Alcatraz has a view of San Francisco.”

In the pages that follow, Kaysen weaves a beautifully crafted portrait of the 18 months she spent at McLean — the infamous psychiatric hospital that housed Sylvia Plath, James Taylor, Ray Charles, and, after Kaysen’s stay, David Foster Wallace — in 1967. The narrative adopts a non-linear form, with characters dying in one chapter, then appearing in the next. This choice causes the book to take the form of a memory, cobbled together based on recollection, time flattened. Kaysen relays the experience of bearing witness to the outside world’s events, the assassinations and protests that came to plague 1968, a series of events transcribed into a television set, viewed by her and her fellow patients as near abstractions.

Toward the back half of the book, Kaysen reflects on her borderline personality disorder diagnosis and, ultimately, presents the notion of mental illness as nebulous. She introduces the concept of two interpreters at the base of our brains, writing: “Imagine the first interpreter as a foreign correspondent, reporting from the world. The second interpreter is a news analyst, who writes op-ed pieces…mental illness seems to be a communication problem between interpreters one and two.” As someone who has long struggled with high-functioning anxiety, I found this illustration one of the most succinct distillations of what happens when your brain feeds you a thought that fails to align with fact, with how you really feel.

By presenting even the most extreme manifestations of mental illness as a slippery slope, Kaysen distills the specificity of her experience in a way that feels accessible to a more generalized reader, resulting in a timeless memoir with a point of view on how we approach mental health individually and collectively.

Darryl by Jackie Ess (2021) — Written by trans Twitter sensation Jackie Ess, this novel follows a 40-something white man from Eugene, OR named Darryl who gets off on watching his wife, Mindy, sleep with other guys (aka: cuckholding, which, at the risk of sounding like a prude who lives under a rock, I had to Google). Despite a growing attraction to one of their thirds and questions around his own gender, Darryl remains adamant about his identity as a heterosexual cisgender man — until “the lifestyle,” as he calls it, prompts him to reevaluate his reality.

Last fall, Brandon Taylor, the novelist behind Real Life, Filthy Animals, and, most recently, The Late Americans, wrote an essay for his Substack, sweater weather, called “against character vapor.” Taylor’s piece opens with the following assertion that comes to shape the whole of the essay: “A character with a body is a social creature while a character without a body, I believe, is a thought experiment.” He then traces modern literature’s shift toward developing characters from the inside out versus the outside in, ultimately urging for a return to the intentional physicality that grounds the works of writers like Henry James and Virginia Woolf.

From my perspective, Ess falls into the trap of character vapor, with the reader thrust into 180 pages of internal monologue, an unintentional epistolary novel without diary pages. That’s not to equate first-person narration with character vapor. Take, for instance Julia May Jonas’s debut, Vladimir. By its end, you have a distinctive sense of the Hudson Valley college where our unnamed narrator and her husband teach, the people who populate it beyond her. In contrast, after finishing Darryl, my grasp on Eugene and its cast of characters still feels fuzzy. As Taylor puts it: “I think that the physical in fiction need not to be totally divorced from the interior. I think in the case of most great literature, they are in fact inlaid with real care and delicacy, and one becomes almost inextricable from the other.” In Darryl, the physical becomes dwarfed by the interior, and, for me, the novel falls short as a result.

Ess’s brand of first-person narration skillfully inserts the reader into Darryl’s sexual questioning, desire, and gender dysphoria, generating insight into a specific experience. And isn’t that carefully crafted brand of vicarious empathy the point of fiction? Yes. But, to an extent, as I see it. I would place Ess’s work in the canon of a new kind of “attention economy writing,” a term I used when trying to describe Madeline Cash’s Earth Angel to a friend back in May. This type of fiction gets written on the Notes app (as Cash admits in an interview with W) and shortened for the imprecise focus of the TikTok generation (Ess explains: “I had a gamble that I could borrow something from slightly dishonored forms of reading like social media archive-binging, and that others would want to read a novel shaped like that.”), prioritizing brevity and interiority over external world building, that “physicality…in full contact with the total matrix of story” that Taylor lauds.

Simply put, this book was not for me, but I’m still glad I read it, as it gave me insight into a foreign experience. Within that, I want to acknowledge my position as a straight, cisgender reader. For a queer or trans audience, the visceral nature of Darryl’s interiority will likely resonate more deeply, potentially — and, if so, justifiably — prompting it to take precedence over what I perceive as the novel’s shortcomings.

Movies of the Month

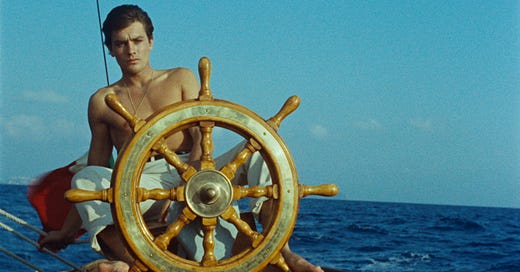

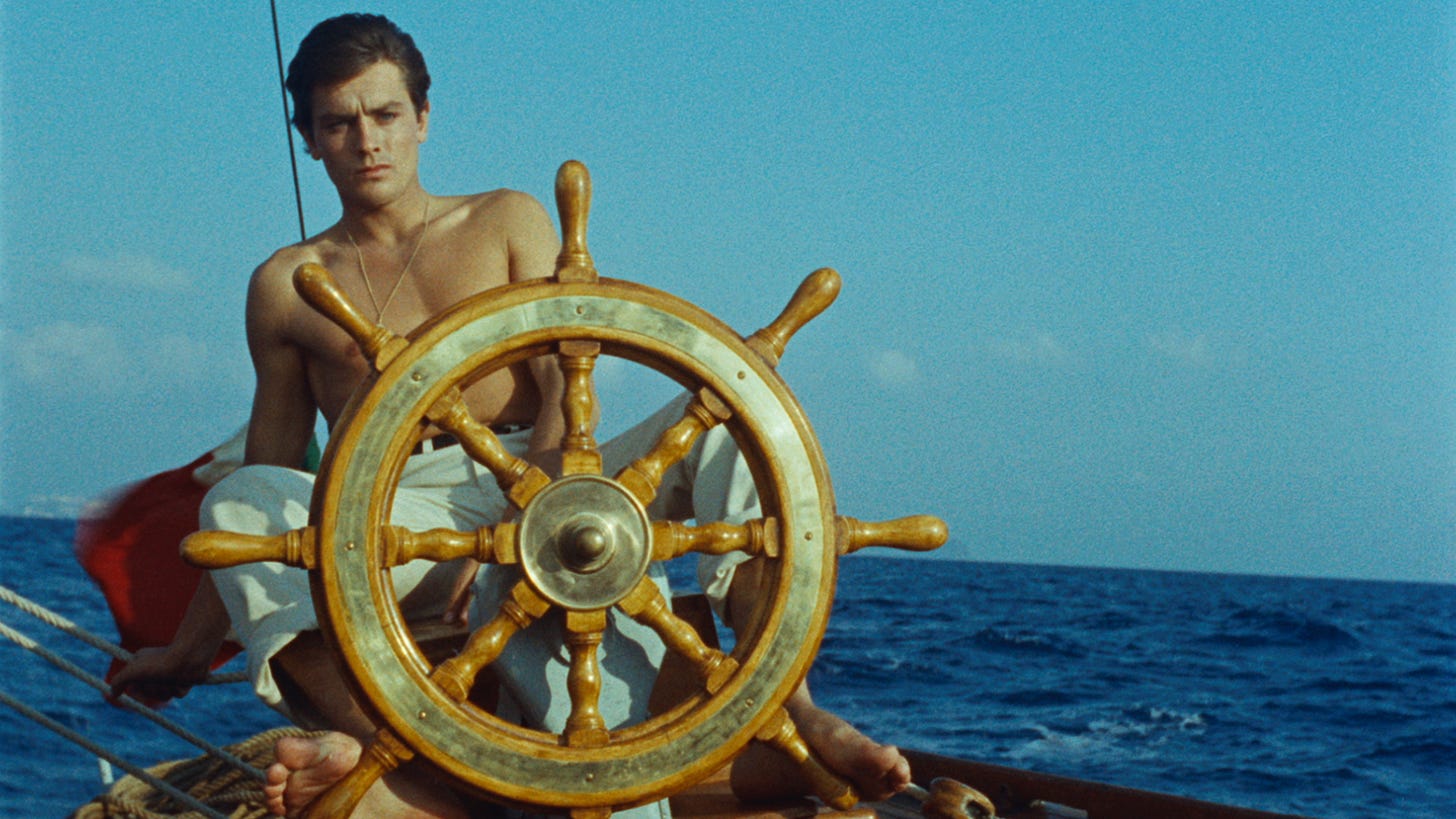

Purple Noon (1960, dir. René Clément) — Before Matt Damon impersonated Jude Law and terrorized Gwyneth Paltrow, Alain Delon impersonated Maurice Ronet and terrorized Marie Laforêt — in French. The Talented Mr. Ripley but directed by René Clément in 1960, Purple Noon has the same dreamy aesthetic and suspenseful plot that have cemented the 1999 film a cult classic summer watch. Come for shirtless Alain Delon on a boat, stay for shirtless Alain Delon on a boat.

Where to Watch: Criterion Channel, Amazon Prime Video ($3.99)

Contempt (1963, dir. Jean-Luc Godard) — Okay, yes, I’m in my French cinema era. If you’re like “okay, I’m only watching one movie in translation this month,” watch Purple Noon, but Contempt was also very good.

Brigitte Bardot plays a 28-year-old former typist and screenwriter’s wife (with the screenwriter played by Michel Piccoli), grounding the film’s genre-characteristic melodrama through her empathetic portrayal. It follows the production of a movie based on The Odyssey (with the production team including Fritz Lang as himself and Jack Palance as not himself). In parallel, it teases out the cracks in the primary couple’s relationship, with the second act — set entirely in their midcentury modern apartment — settling into their dynamic in an almost novelistic way. Striking visuals dominate the cinematography, with pops of red creating continuity across scenes.

As someone with an aversion to overplotting, I found the ending a bit too dramatic, but that’s French New Wave, I guess. I also recommend checking out Roger Ebert’s review from 1997 after watching for a lol.

Where to Watch: Film Forum, Criterion Channel, Amazon Prime Video (premium subscription)

The Lost Weekend (1945, dir. Billy Wilder) — I had the pleasure of seeing this harrowing, artful portrayal of addiction on 35mm as part of Film Forum’s Billy Wilder Festival (more below). The film opens with our protagonist and resident alcoholic Don Birnam (played by Ray Milland) getting ready to go away for the weekend with his brother, Wick (played by Phillip Terry) at the encouragement of his girlfriend, Helen St. James (an iconic media girlie with a fabulous leopard-print coat who frequents the Met Opera and works at TIME Magazine, played by Jane Wyman). Instead, things go a bit sideways as we follow Don on a weekend-long bender.

Toward the start of the movie, Don’s go-to bartender, Nat (played by Howard Da Silva) tries to wipe away a rim of condensation left by a whisky glass. Don protests, saying: “Don't wipe it away, Nat. Let me have my little vicious circle. You know, the circle is the perfect geometric figure. No end, no beginning.” This quote lays the foundation for the structure that ultimately shapes the film, as we embark on a non-linear narrative (my favorite kind) that teases out Don’s relationship with Helen, anxiety around his failed writing career, and unrelenting grip on the bottle. Based on Charles R. Jackson’s autobiographical novel of the same name, the film wraps with a meta nod to its origins that, to me, felt fitting and poignant.

Wilder captures a certain version of the city that, to a modern New Yorker, feels foreign. One of my favorite shots features a hungover Don limping uptown 40 blocks while the Third Avenue El looms in the background. (For those of you unfamiliar with it, the Third Avenue El marked the last operational elevated train in Manhattan at the time of its demolition in 1955. You can read more about its history here.) The characters go out in Midtown unironically. You get the idea.

Where to Watch: Film Forum as part of the Billy Wilder Festival (playing at 8:45 PM on 8.1), Amazon Prime Video ($3.99)

Basquiat (1996, dir. Julian Schnabel) — Shot like a season one episode of Sex and the City, this movie provides an incredibly 90s look into the all-too-short life of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Beautifully scored by Schnabel and John Cale (of my favorite band, The Velvet Underground), the film underscores the prescience of Basquiat’s vision and teases out his friendship and working relationship with Warhol (played by Bowie).

At times, the tone seems to vacillate between that of an art film and that of a mainstream drama, but I overall would recommend, especially if you saw Basquiat: King Pleasure in New York or LA.

Where to Watch: YouTube

The Goldfinch (2019, dir. John Crowley) — Wow, Ansel Elgort is so bad in this movie. Like, laughably bad. And spends the entire movie dressed like a socially stunted Morgan Stanley VP. But I digress.

For those of you unfamiliar, this film, based on Donna Tartt’s 2014 novel of the same name, follows Theo Decker (played by Elgort as an adult and Oakes Fegley as a child) after an explosion at the Metropolitan Museum of Art throws his life irreparably off course. The star-studded cast included not only Elgort, but also household names like Nicole Kidman and Luke Wilson.

Kidman kills it, as always, and Fegley crafts a tender portrayal of young Theo, but, beyond that, the film, to me, felt too heavily plotted. The world felt immersive and the premise compelling, but I ultimately ended up wishing the film had prioritized giving the audience more space to sink into the characters.

Also, ICYMI: Tartt fired her agent over this movie lol.

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime (premium subscription)

Barbie (2023, dir. Greta Gerwig) — Splash meets The Truman Show. Five stars, no notes.

Where to Watch: ~a theatre near you~

Nha Fala (My Voice) (2002, dir. Flora Gomes) — Shot between Cape Verde and France, this musical follows a woman named Vita (played by Senegalese French actress Fatou N'Diaye) whose family believes that, if she sings, she will die. Before embarking to Paris for school, she promises her mother she will never sing, a vow she intends to keep — until love shifts the course of her plans.

Visually stunning, this film had gorgeous settings, color schemes, and costumes. N'Diaye and Jean-Christophe Dollé, the French actor who plays her character’s lover, Pierre, maintain strong chemistry too. Unfortunately though, the scenes designed to establish the setting — especially the musical ones — often felt too long, while those moments focused on relationships seemed rushed, resulting in what, for me, felt like a low-stakes, emotionally empty narrative.

Where to Watch: Unclear, but potentially MUBI. I saw it as part of Albertine’s Films on the Green series.

The Seven Year Itch (1955, dir. Billy Wilder) — Marilyn Monroe is absolutely phenomenal in this film, the perfect summer in the city watch. It captures the Mad Men-sanctioned tradition of Manhattan men sending their wives and children out east or upstate for the summer while they stay in the city to work, indulging in infidelity, liquor, and cigarettes. 39-year-old-but-looks-much-older publishing executive Richard Sherman (played by Tom Ewell, reprising his role in George Axelrod’s 1952 three-act play of the same name) starts out determined not to fall victim to the same pattern as his peers when his wife, Helen (played by Evelyn Keyes), and son, Ricky (played by Tom Nolan), leave for Maine. But things take a turn when an unnamed model and actress (played by Marilyn Monroe) starts subletting the un-airconditioned apartment upstairs.

Co-written by Wilder and Axelrod, this romcom encapsulates the musings of an anxious mind to a tee. Much of its first act takes the form of an ongoing monologue from Richard, whose overactive imagination creates fabricated scenario after fabricated scenario. Initially, each one reflects his sexual fantasies, but, as the narrative progresses, they morph to match the guilt-ridden terror coalescing around those desires. His desperation begin as a source of humor – thanks in large part to a strong performance by Ewell, a skilled physical comedian – but his delusional inner monologues grow old quite quickly. Thankfully, enter Monroe, who, from my perspective, carries the film.

Some may debate Some Like It Hot (1959) versus Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953) as Monroe’s magnum opus, but I’d make the case for The Seven Year Itch (1955). After dropping a tomato plant on Richard’s patio while watering it with a cocktail shaker (“a little silver one”), she comes downstairs for a martini (“A glass of that! A big tall one!”), followed by her own hostess gift of potato chips and champagne. Despite initially lying about his marital status, Richard slowly comes clean, and a compelling dynamic emerges. Monroe’s character feels soothed by it, relieved to make a male friend with no ulterior motives (“A married man, air conditioning, champagne, and potato chips. This is a wonderful party!”), while Richard continues to view her on wholly sexual terms.

Tension underscores the whole of the narrative, much of it internal and stemming from Richard. But, from my perspective, the most interesting iteration comes in the form of this disconnect between Richard and Monroe’s character, what they have and what they want from their relationship, from what ultimately becomes a friendship. Monroe’s character seems uninterested in not just Richard but dating as a whole, indulging in the sparkle of the city and her burgeoning career above all else (“That’s what’s wonderful about a married man. No matter what, he can’t ask you to marry him. He’s already married, right?”). Meanwhile, through the lens of Richard’s perspective, she lacks a name, an identity, existing exclusively as a conduit to his fantasies, an instigator for his anxieties. (On IMDB, Wikipedia, etc., Monroe’s character gets named as simply “The Girl.” At one point toward the film’s end, he refers to her as “whatever your name is.”)

This breach in priority, of intent, drives a particularly comedic scene wherein Richard fixes a pair of drinks, soliloquizing about their undeniable sexual pull. Simultaneously, pictured above, Monroe’s character obliviously mutters to herself, debating asking to sleep on his couch to finally escape her sauna of an apartment, to get some air-conditioned rest ahead of her show in the morning.

Monroe’s performance gives life to a situation most women I know have faced at one point or another; what Richard views as enticement is simply her character moving through life.

Where to Watch: Tubi (free), Amazon Prime Video ($3.99)

Upcoming Content to Consume

Film Forum: Written and Directed by Billy Wilder (Dates: 8.1-8.3) — Look, I love a Billy Wilder movie. In fact, when Film Forum announced this festival, I was shocked to realize just how many of my favorite movies he’s behind, namely Sabrina (1954), Double Indemnity (1944), Sunset Boulevard (1950), Some Like It Hot (1959), and The Apartment (1960). You can still catch a few of them before this series wraps in a couple of days! Personally, I would prioritize The Lost Weekend on August 1st and the 35mm screening of Double Indemnity on August 3rd.

Film Forum: Thelma and Louise (1991) (Dates: 8.4-8.10) — I surprisingly have never seen this movie, so will absolutely be using Film Forum’s week-long screening as an opportunity to fill that gap. Karina Longworth, creator, writer, and host of Hollywood-history podcast You Must Remember This, will introduce the 8:40 PM screening on 8.4.

Cinespia at Hollywood Forever Cemetery: Pretty Woman (1990) Date: 8.12) — For my West Coast subscribers! If I could fly across the country just to watch one of my top three favorite romcoms (the other two being Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001), which Air Mail recently wrote about for the 25th anniversary of the book’s publication, and When Harry Met Sally (1989), obviously) in an LA cemetery, I would.

McNally Jackson Seaport: Cleo Qian presents LET'S GO LET'S GO LET'S GO, in conversation with Katie Kitamura (Date: 8.14) — I’m intrigued by this debut short story collection, which is slated to explore “the alienated, technology-mediated lives of restless Asian and Asian American women today.” Plus, I love a McNally Jackson Seaport event (although get there early if you plan to go because seating’s always limited) and moderator Katie Kitamura, who wrote Intimacies, one of my favorite 2021 reads.

Film at Lincoln Center: Boogie Nights (1997) on 70mm (Dates: 8.18-8.19) — PTA’s magnum opus in 70mm. If you want to roll through an analysis from The Bret Easton Ellis Podcast afterward, which you know I recommend, here’s a link.

Village East by Angelika: Roman Holiday (1953) (Date: 8.21) — A summer classic at one of the city’s most underrated theaters. If you go, I highly recommend turning it into a double feature by streaming Summertime (1955), aka: Kate Hepburn in her study abroad era, when you get home. Or just watch both on the couch with a Campari spritz!

Miscellaneous Musings

From the Desk of Marlowe Granados — Marlowe Granados’s debut, Happy Hour, was one of my favorite novels of 2021 — and a perfect August read if you haven’t picked it up already. I made the fatal mistake of finding it in the dead of winter, and it made me crave a sipping a Joe iced chai on blistering summer day a decade earlier, entrenched in think piece on a new episode of HBO’s Girls, Lana del Rey’s Born to Die humming along in the background. The epistolary novel follows two 21-year-old best friends, Isa and Gala, as they drift through the summer of 2013 in the city. Told through Isa’s diary entries, it floats out east and back again as the girls slip into party after party, relying on charm to secure countless French 75s. As their cash dwindles, tension starts to simmer.

Since Happy Hour’s publication, Granados contributed to publications ranging from The Cut to NYLON to Air Mail until finally launching her Substack, From the Desk of Marlowe Granados, at the end of June. As Granados put it: “You may be wondering WHY—you thought I thought Substack was corny! Now, a girl is allowed to change her mind. But ALSO (and maybe I have an artistic temperament), I have found writing for publications rather… bleak. I am known for a particular voice in my writing, and when I am tasked with writing for somewhere else there are times much of my style is washed away to make it sound like it could have been written by anyone. I just don’t understand why they would get ME to write something if that’s the plan. It feels like bad business sense, and honestly that’s none of my business!”

So far, Granados’s pieces are extremely aligned to my interests, with recent ones covering everything from why your first apartment matters to the value — and “glamour” — of always having crepes on hand.

“The Swimmer” by John Cheever — This short story first ran in the July 10, 1964 edition of The New Yorker and went on to influence Emma Cline’s latest novel, The Guest, one of my favorite June reads. (You can check out my friend Ama’s review of it in Los Angeles Review of Books here.)

Happy Hour meets My Year of Rest and Relaxation, The Guest follows Alex, a 22-year-old sex worker, who grifts her way across Long Island in search of housing after a misstep at a party gets her evicted by her older boyfriend, Simon. Killing time as it creeps closer to Labor Day weekend — and Simon’s big end-of-summer party —, Alex finds herself on the outside of a twenty-something friend group’s Airbnb, the nanny circuit at a local beach club, and the cult of the Hamptons as truth and fiction splinter and converge.

But back to “The Swimmer,” which Cline cites as an inspiration in multiple interviews about her new novel. The narrative feels like floating down a river on a hot summer day. We follow a drunken gentleman, a husband and father, as he wanders in and out of his neighbors’ pools, through the yards of his peers. Darkness slips in and out of the frame as our unreliable narrator continues his quest to swim across the “string of swimming pools…[the] quasi-subterranean stream that curves across the county” — until it finally short circuits the picture.

Once Upon a Time…at Bennington College — I adore writer Lili Anolik, the late Eve Babitz’s biographer who regularly contributes to Vanity Fair and Air Mail. In 2019, she wrote a piece for Esquire called The Secret Oral History of Bennington: The 1980s’ Most Decadent College, unpacking the culture behind the college that included my (parasocial) bestie Bret Easton Ellis, Donna Tartt, and Jonathan Lethem among its class of 1986.

On the heels of that piece, Anolik launched Once Upon a Time…at Bennington College, a podcast that delves into the upbringings, undergraduate lives, and careers of the aforementioned trio of authors. As a certified Bret stan, a lot of the information around him wasn’t new to me, but the details revealed about hyperprivate Donna and the influences at shaped The Secret History definitely were.

This podcast feels like sitting in a coffee shop (or, at a cafeteria table, as Anolik would say), dropping a sugar cube into your cappuccino, and eavesdropping some really good gossip dropping at the next table.

Also, Caroline Calloway randomly shows up in the last episode?? Idk, guys.

Supplemental Reading

Quick tip: If any of these pieces (or links throughout this newsletter) live behind a paywall for you, you can plug the URLs into this site to view them.

Air Mail: The Cult Around the Corner

Vogue: Barbara Palvin Wore Vivienne Westwood to Marry Dylan Sprouse at Their Hungarian-Countryside Wedding

RogerEbert.com: Faith in Life: Jane Birkin (1946-2023)

The New Yorker: How Larry Gagosian Reshaped the Art World

Cocktail of the Month

You know what I love? Sipping on a cocktail while I consume content. So, each month, we’ll close out with a cocktail recipe to try at home, starting with…

Paper Plane —

It took me, as a bourbon drinker, a while to find the perfect summer cocktail — until I stumbled on the Paper Plane, which basically feels like Don Draper’s version of an Aperol Spritz.

To make it, add one ounce each of freshly squeezed lemon, Aperol, Amaro Nonino, and Bourbon to a cocktail shaker filled with ice. Shake and strain into a coupe glass to serve.

Until next month!

xo, Najet