On Vibes in Fiction and Film

"No one has ever vibed their way to victory." -my Capricorn friend, determined to hurt me

When discussing Emma Cline’s The Guest recently, one of my friends joked-but-not-really-joked I should get a t-shirt that says “I am only here for the vibes.” She’s not wrong. When I consider what distinguishes compelling content for me, one simple, overused word forms as the answer: vibes.

The Oxford English Dictionary by way of Google defines a vibe as “a person's emotional state or the atmosphere of a place as communicated to and felt by others.” In discussing fiction, Joan Didion once said: “Quite often you want to tell somebody your dream, your nightmare. Well, nobody wants to hear about someone else’s dream, good or bad; nobody wants to walk around with it. The writer is always tricking the reader into listening to their dream.” From my perspective, vibe-driven fiction and film situates its reader, its viewer, at the nexus of an internal emotional state and an external place; in other words, it tricks the reader, the viewer, into listening to the dream.

ELLE recently ran a piece entitled: “Who Needs Plot When You Have Vibes?” (Can I get that on a hat?) In it, freelancer Caelan McMichael argues, in the realm of fiction, that “‘no plot, just vibes’ novels give authors space to play — and readers the opportunity to truly be seen.” She writes: “Per BookTok, the cornerstone of the ‘no plot, just vibes’ canon is Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation, which documents a woman literally lying around for most of the novel, self-sedating with a potent cocktail of pharmaceuticals. Sally Rooney’s Normal People and Conversations With Friends are also often cited, along with Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy, Halle Butler’s The New Me, and Elif Batuman’s The Idiot. BookTok users have also reclassified timeless works like Mrs. Dalloway, The Bell Jar, and Franny and Zooey as light on plot but heavy on vibes.” McMichael implies plot-driven novels as those that walk the reader through a rising, then falling, series of actions, moving toward, then away from, a climax. On the other end of the spectrum, “no plots, just vibes” novels consist of a series of smaller actions, their comparative importance to one another more or less flattened.

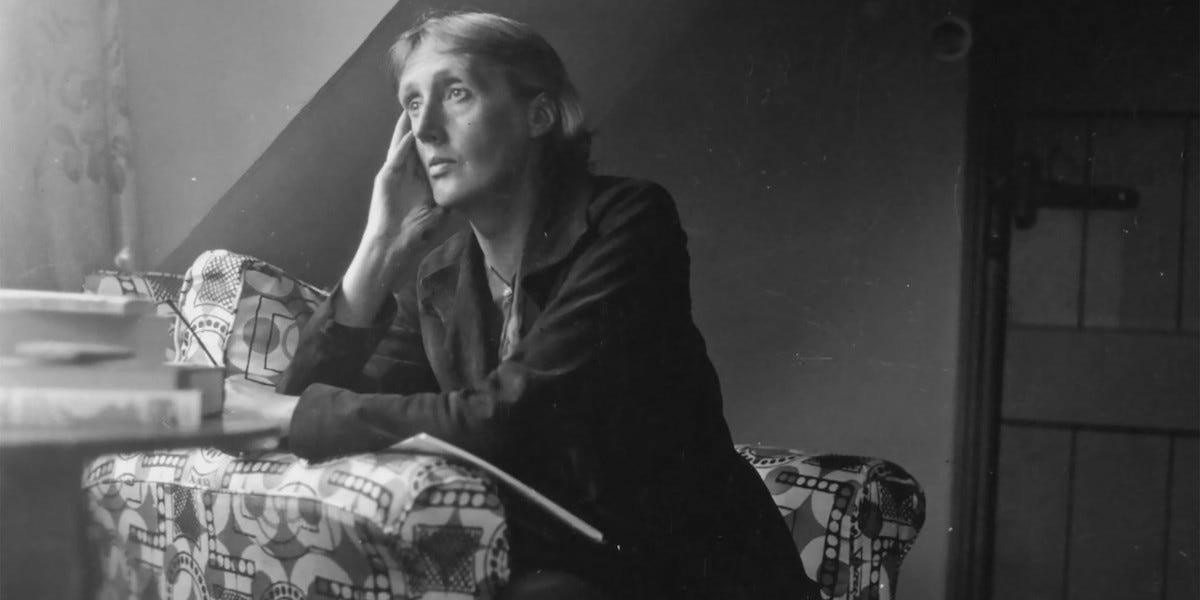

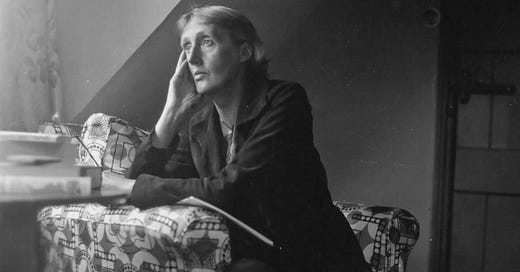

In her 1919 essay, “Modern Fiction,” Virginia Woolf makes an early case for the “no plot, just vibes” canon, writing: “Examine for a moment an ordinary mind on an ordinary day. The mind receives a myriad of impressions — trivial, fantastic, evanescent, or engraved with the sharpness of steel. From all sides they come, an incessant show of innumerable atoms; and as they fall, as they shape themselves into the life of Monday or Tuesday…if [a writer] could write what he chose, not what he must, if he could base his work upon his own feeling and not upon convention, there would be no plot, no comedy, no tragedy, no love interest or catastrophe in the accepted style…Life is not a series of gig lamps symmetrically arranged; life is a luminous halo, a semi-transparent envelope surrounding us from the beginning to the end.” Here, Woolf aligns classical notions of plot with commercial expectations, examinations of “an ordinary mind on an ordinary day” with the writer’s true literary impulse. Sweetbitter author Stephanie Danler echoes this artistic ideal in her latest Substack post, writing: “I remind myself to approach every mundane moment as if that too could be art. I tell myself: Slow down…stare out the window while drinking tea.”

In the ELLE piece, McMichael clarifies that “no plot, just vibes” novels do, in fact, include plot, but a covert kind that lurks beneath veneers of listlessness. Discussing her debut, Happy Hour, my girl Marlowe Granados (pictured above) says: “When people say nothing really happens in the novel, I find it funny because something happens every night with the girls. When you put it all together, there’s not this traditional structure of rising and falling action, because I’m not interested in that…for me, plot is just an accumulation of moments, and it doesn’t necessarily have to be so rigid in structure or formulaic. That doesn’t reflect how people live their lives.” Vibes-first fiction captures “an accumulation of moments” through the lens of a sweeping mood, one that possesses the power to transcend plot in the traditional sense of the term by embracing how minutiae can accumulate to form meaning.

Bret Easton Ellis’s latest novel, The Shards, embodies this idea. In discussions around the book’s development, my problematic parasocial bestie Bret invariably brings up the early days of COVID. Locked down in his apartment like the rest of us, he grew bored and began looking up old classmates from Buckley. His imagination churned over the missing ones, those individuals without an online presence, provoking a desire to return to a certain place, a particular time. The place: Los Angeles. The time: 1981. The Shards undoubtedly has a plot, one driven by a serial killer stalking the San Fernando Valley, by the romantic entanglements of a fictional 17-year-old Bret and his friends, but it emerges as secondary to the impetus that birthed the novel: real, 57-year-old Bret’s yearning to conjure a bygone era.

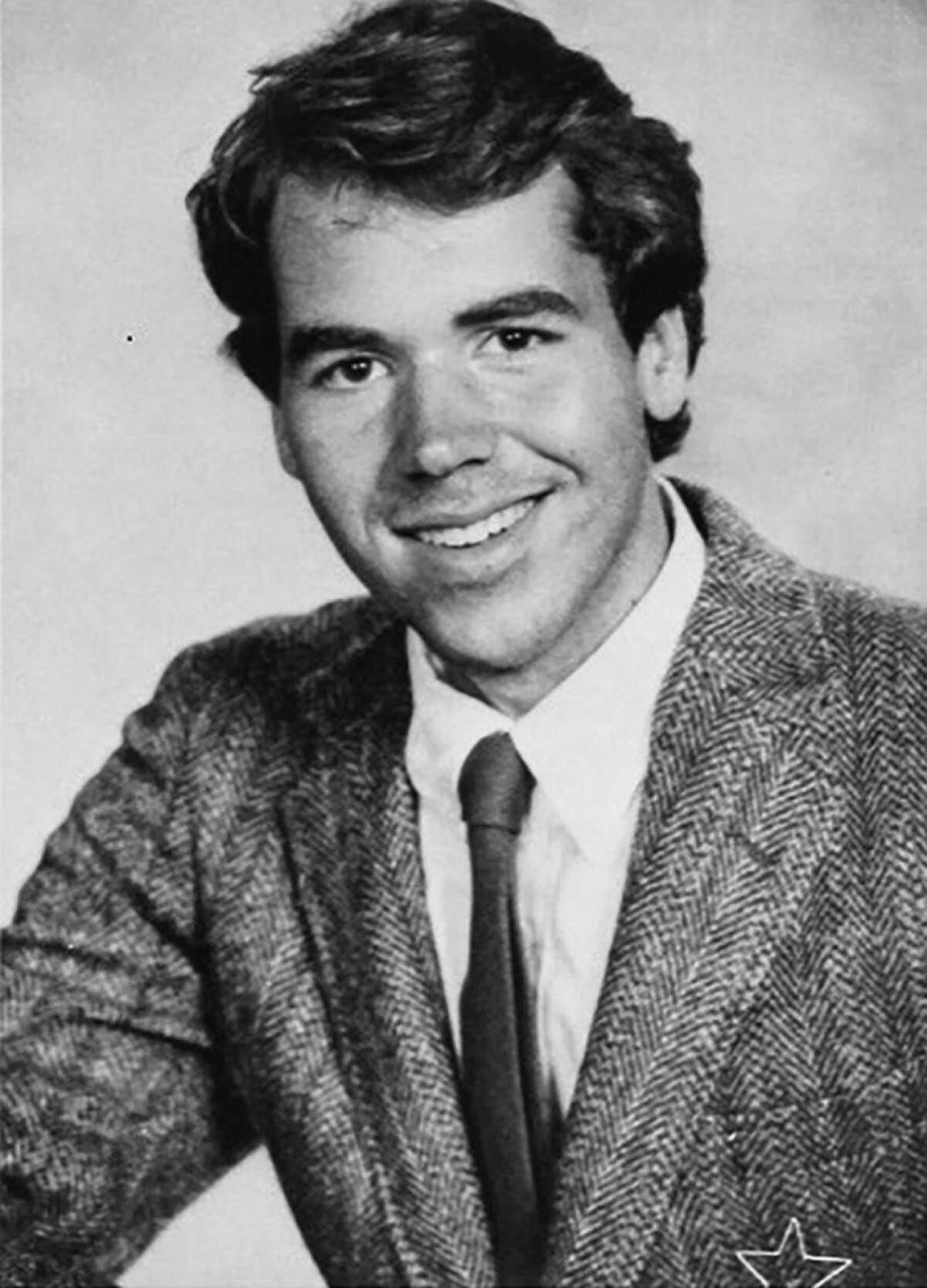

Clocking over 600 pages, The Shards includes in-depth descriptions of long-gone and changed spots like The Sherman Oaks Galleria, Flipper’s, and The National Theatre, wrenching readers into the archives of the author’s memory. Vanity Fair columnist Nate Freeman writes: “Fact, fiction, and autofiction seemingly all start to blur. Ellis’s own 1982 yearbook picture is on the back flap of the book. It comes after a disclaimer that says that all the characters in The Shards are fictional, apart from the narrator.” Early 80s anthems, from Ultravox’s “Vienna” to Blondie’s “Dreaming,” score the pages, the young narrator’s mind, and now comprise an encyclopedic fan-made Spotify playlist.

The Shards reflects a holistic authorial vision, a world carefully constructed through details as minute, as all-encompassing, as Bret’s senior yearbook photo on the back flap (pictured above). Quentin Tarantino’s 2019 film, Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood, demonstrates how this principle can play out through the medium of movies. The Hollywood golden age homage captures a last gasp of innocence, the dusk of the 1960s. It showcases shifts in the studio system, with fading actor Rick Dalton (played by Leonardo DiCaprio) and his former stuntman Cliff Booth (played by Brad Pitt) weathering the changes. Much like Bret in The Shards, Tarantino resurrects a lost version of Los Angeles, animates an alternate iteration.

The film’s action occurs across two days six months apart: February 8, 1969 and August 8, 1969, the latter of which, as most Southern California natives innately understand, gave way to a dark mark on the city’s history. As Joan Didion famously wrote in The White Album: “Many people I know in Los Angeles believe that the Sixties ended abruptly on August 9, 1969, ended at the exact moment when word of the murders on Cielo Drive traveled like brushfire through the community, and in a sense this is true. The tension broke that day. The paranoia was fulfilled.” Rather than focus on darkness lurking beneath the decade-defining promise of free love, Tarantino elevates light through his representation of Sharon Tate (played by Margot Robbie).

While Rick and Cliff battle precocious child actors and hitchhiking cult members, Sharon goes about her life with a carefree joy that reflects the best parts of the 60s. She buys a copy of her favorite book, Tess of the D'Urbervilles, at a long-closed used bookstore in Westwood; parties at the Playboy Mansion with Steve McQueen, Michelle Phillips, and “Mama” Cass Elliot; catches a screening of her own performance in The Wrecking Crew. Tarantino’s approach to the Sharon character drew criticism coming out of Cannes, with naysayers slamming Robbie’s lack of dialogue in the final cut (which, for the record, Sharon’s sister Debra loved). But that myopic focus fails to consider the larger force of her presence.

As Far Out film writer Calum Russell puts it: “Quentin Tarantino approaches the death of Sharon Tate in 1969 with a similar understanding of such cultural importance, placing her at the very centre of his sprawling epic that seeks to illustrate such winds of change that would influence the late 20th century…Sharon Tate is the vehicle to drive the true nuance and yearning of Quentin Tarantino’s nostalgic classic, with the gleaming smile of Margot Robbie as the iconic actor reflecting the same ignorant bliss of every American individual at the turn of such national change.” In other words, Sharon is the vibe, and the vibe is the whole point.

Vibes intersect with quality where style serves as scaffolding. While vibes depend on the marriage of internal emotional state with place, style operates primarily in the realm of the external. In film and television, it remains predicated on an aesthetic combination of audio and visual. Think of Tarantino’s montage of neon lights illuminating as darkness descends on 1969 Los Angeles or the infamous Copacabana scene in Goodfellas. These types of scenes invariably merge music, from The Rolling Stones’s “Out of Time” to The Crystals’s “And Then He Kissed Me,” with striking shots to capture moods. Tarantino memorializes nightfall on August 8, 1969, playing on historical hindsight to distill the sense of quite literally being out of time. Martin Scorsese encapsulates the starry-eyed blindness of early-days romance as Karen (played by Lorraine Bracco) follows Henry (played by the late, great Ray Liotta) down the stairs of New York’s then-hottest nightclub, into the depths his lifestyle. These examples serve as individual instances in two films filled with comparable moments, the aggregate of which coalesce to create consistency of style. To consider how this conception of style translates to fiction, think of The Jonathan Club on an overcast afternoon, Melrose littered with long-gone clubs, and The Polo Lounge on an early 80s afternoon, set to the soundtrack of faded top-40 hits, in The Shards.

Fiction becomes a vibe rather than merely stylized when its narrative voice — regardless of tense — embeds interiority with the outside world. In her debut, Vladimir, Julia May Jonas writes: “Like every year, the cold came more quickly than expected. The day after the pool guy came there was a sudden frost, and the dirt froze into a spongelike formation that crunched when stepped on. That morning I pulled out my white woolen cardigan that I bought from the Salvation Army in my twenties and layered it over a long flannel nightgown with bulky fisherman’s socks and my indoor sandals.” This passage situates the unnamed narrator in an external environment marked by sudden cold, frozen dirt, inescapable chill. It reveals age and leaves the reader to discern what the choice to pair a cardigan with a flannel nightgown, “bulky fisherman’s socks,” and indoor – not outdoor – sandals says about her. In the span of three sentences, the reader learns something about this woman’s inner and outer life.

If this were an essay advocating for traditional notions of plot, I’d probably try to underscore a certain point or argument at this juncture. But, since it’s not, since I’d really rather just vibe my way through to the end, I’ll stop here.

I think you’re the most intelligent person I know

Favorite one yet I think!! :) :)