So, not that I need to explain because quality over quantity (@ the Goodreads industrial complex), but I only read one book in full this month for two reasons.

First, I spent Labor Day and the week after it re-reading The Shards by the pool in California (as God intended) for my book club, which led to a lot of the reflections in my “On Vibes in Fiction and Film” piece from last weekend.

Second, I started a short story workshop through The Center for Fiction the following week that has continued through the balance of the month. It’s had a fairly intense reading and writing curriculum, leaving me with less time than usual for long-form fiction, but the Miscellaneous Musings section of tomorrow’s October issue will highlight a couple favorite short stories I’ve come across through the course.

In the meantime:

Love by Hanne Ørstavik (2018) — Translated from the original Norwegian by Martin Aitken, this “icy nocturne of a novel,” as the front flap so aptly puts it, follows one night in the lives of a small-town mother, Vibeke, and her nearly-nine-year-old son, Jon. On the eve of Jon’s birthday, both embark on separate yet similarly eerie adventures through their new town in the north of Norway. The title serves as a bit of a misnomer, with the disconnect between the two characters driving the book’s deliciously meandering plot and inventive style.

In an interview with Bookaholic, Ørstavik discusses how her own experience as a single mother shaped the novel, saying: “I don’t know to what extent the characters feel love: one of the scariest things in the novel is that you don’t really know that. Vibeke does all the right things for Jon – except that night when she should have been there, she should have remembered his birthday –, she takes care of him, she cooks for him, she takes him to school. From the outside, she does all the right things, she’s a good mother. But is she? That is quite the question of the novel. What is to love and how does that show?” A haunting meditation on parent-child relationships, Love grapples with desperation for its namesake, where it comes from, who wants it from whom.

Two years ago almost to the date, I read Jonathan Safran Foer’s bestselling 9/11 novel, Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, told from the perspective of a nine-year-old boy named Oskar whose father dies in the World Trade Center. In it, Safran Foer’s first-person narration captures the quintessence of anxious thought patterns, how they begin in a child before enveloping an adult. Oskar has a knack for inventing things, theoretical mechanical solutions to problems. At one point, he states: “In bed that night I invented a special drain that would be underneath every pillow in New York, and would connect to the reservoir. Whenever people cried themselves to sleep, the tears would all go to the same place, and in the morning the weatherman could report if the water level of the Reservoir of Tears had gone up or down.” His inventions often serve as imaginings of worst-case scenarios, with Oskar explaining that he “tried to invent optimistic inventions. But the pessimistic ones were extremely loud."

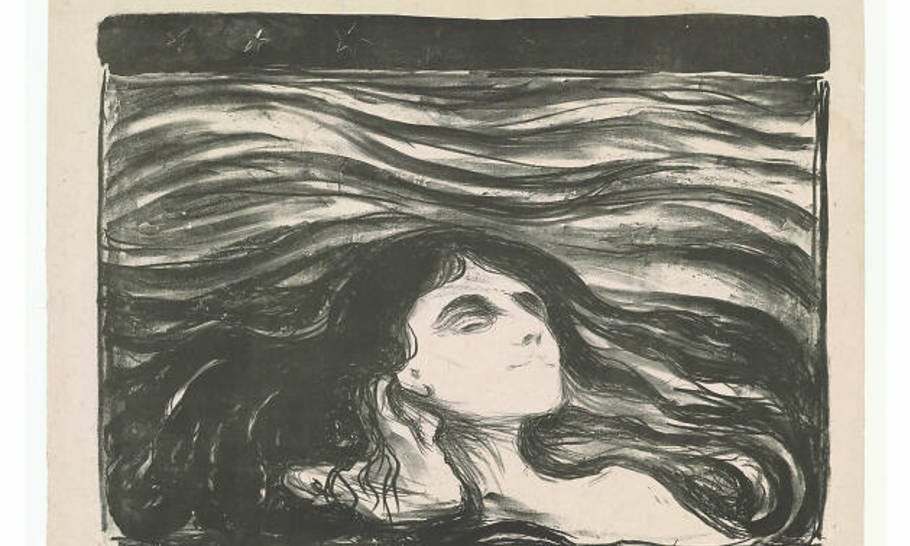

In Love, Jon reflects an analogous mindset through a third-person lens. At one point, Ørstavik writes: “He imagines the squiggles of light he sees beneath his eyelids to be undiscovered galaxies. He tries to figure out what to do, whether to land somewhere or be heading into battle, preparing himself for the enemy’s onslaught.” Jon’s imagination, much like Oskar’s in Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, reveals the presumption of lurking danger, epitomizes the childhood origins of adulthood anxiety. Vivid visual, auditory, and tactile descriptions distinguish the prose. For instance, the visual, above. The auditory: “The girl’s turned the sound up even more. It’s loudest in Jon’s left ear, he feels like his head’s one-sided.” The tactile: “The engine idles, puffing its exhaust. Jon feels its warmth against his lower legs.”

Love reads like a poetic screenplay, one characterized by not only descriptive detail, but also quick cuts. The perspective switches between Vibeke and Jon paragraph after paragraph without any particular pronouncement from the narrator. For example, Ørstavik writes: “Her parents have dark hair, but the girl’s hair is nearly white. Just like mine, Jon says to himself. ‘Wait,’ says Vibeke. ‘What for?’ he says.” “Wait” indicates a cut to a different scene, Vibeke in a kitchen with a strange man (“he”). Ørstavik trusts imaginations to meet her halfway, flashing between concurrent scenes instead of walking the reader into and through each one; as moments merge and unravel, a spooky, stunning fever dream of a world emerges.

A short one this month! I’m almost done with The Vegan by Andrew Lipstein, self-reviewed by the author as “one of the best, if not THE best, book about veganism and high finance out this year,” and look forward to sharing thoughts next month.

In the meantime, keep an eye out for September movie reviews later today and the October newsletter tomorrow!

xo,

Najet