Hello, and Happy New Year!

Let’s get into it:

January Book Selections

As was the case last January, we’re going to take a bit of a different approach to this newsletter. Instead of the usual book recommendations, I’ll share my top ten favorite reads of 2024 for you to check out in 2025, with description excerpts pulled from my past reviews.

These books aren’t necessarily the highest quality ones I read, but they are the ones I enjoyed most for various reasons.

Here we go, in order:

Stoner by John Williams (1965) — Bukowski once said: “An intellectual says a simple thing in a hard way. An artist says a hard thing in a simple way.” I adore this novel for Williams’s ability to write as an artist, to distill the full scope of a life with tender immediacy.

This underrated classic — lauded by The New Yorker in 2013 as ‘the greatest novel you’ve never heard of’ — traces the life of University of Missouri English professor William Stoner. The opening paragraph gives a brief overview of Stoner’s career, noting that, “when he died his colleagues made a memorial contribution of a medieval manuscript to the University library…An occasional student who comes upon the name may wonder idly who William Stoner was, but he seldom pursues his curiosity beyond a casual question.” With the framework of Stoner’s life and death established, the ensuing 270 pages fill in the specifics with a finer brush.

Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh (1945) — If 2018’s “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination” holds the top slot for your favorite Met Gala theme, do I have a novel for you.

Set during World War II, Brideshead Revisited (1945) opens with Charles Ryder and his battalion sent to new headquarters at a country estate called Brideshead. The property propels Charles’s memory back to 1922, to his early days at Oxford, and chronicles his entanglement with the Flyte family, the home’s aristocratic owners, over the course of two decades. Rising sociopolitical tensions in Europe, the impending inevitability of World War II, creates a kind of pressure cooker for the narrative. The novel’s denouement dovetails with the final days before Hitler’s invasion of Poland, with what, in his preface from 1951, Evelyn Waugh characterizes as “a bleak period of present privation and threatening disaster.” Brideshead becomes a reflection of the Flyte family and the Flyte family the embodiment of England, a country haunted by shrinking stability by the summer of 1939 (“The weeks of illness wore on and the life of the house kept pace with the faltering strength of the sick man.”).

From my perspective, Brideshead Revisited operates, above all, as a novel about place. The country estate itself emerges as a site that bears witness to the changing tides of a family, of a country (“‘It doesn’t seem to make any sense — a family in a place of this size. What’s the use of it?’ ‘Well, I suppose Brigade are finding it useful.’ ‘But that’s not what it was built for, is it?’ ‘No,’ I said, ‘Not what it was built for.’”).

The Stepdaughter by Caroline Blackwood (1976) — This McNally Editions reissue reads like a creepy fairytale, one reimagined on the Upper West Side of the 1970s from the perspective of J., a new kind of evil stepmother (“I find Renata very ugly. I am therefore in no way jealous of her beauty, but in other ways my attitude toward her is much too horribly like the evil stepmother of Snow White.”) As writer Gideon Leek puts it in his LARB review: “Perched high above the traffic of the Upper West Side…she’s a nightmare in a nightgown, a mean spirit in a mink coat, an insult comic trapped in a high-rise.”

This slim epistolary novel consists of imaginary letters written by J. — notably, in her mind — to no one (“I am only writing letters in my head because I am jealous of the young French girl Arnold has sent over to me from Paris. Monique…writes real letters whenever she is given a moment’s peace to write them. My letters are written entirely out of rivalry, always end up as something unmailed and useless in my brain.”). J.’s husband, Arnold, has fled to Paris in pursuit of a younger woman and left her alone with their toddler, Sally Ann; an au pair, Monique; and his 13-year-old daughter from a prior marriage, Renata. An awkward child obsessed with making cakes from boxed mixes, Renata bears the brunt of J.’s artistic and romantic impotence (“The girl obsesses me. All the anger I should feel for Arnold I feel for Renata.”). J.’s grip on reality teeters and tips as the aperture of her husband’s abandonment sharpens.

Bright Lights, Big City by Jay McInerney (1984) — Days of Abandonment (2002) for men, Bright Lights, Big City (1984) inhabits the headspace of a 24-year-old fact checker at a prestigious magazine, a fictional iteration of The New Yorker drawn from author Jay McInerney’s early 1980s experience at the publication (“In fact, you don’t want to be in Fact. You’d much rather be in Fiction.”). His wife, Amanda, a Kansas City country bumpkin baptized by the Manhattan modeling world, has left him and moved to Paris. Grief clouds the narrator as he struggles to hold onto his job and snorts his way through late nights at The Odeon (“It is worse than you expected, stepping out into the morning. The glare is like a mother’s reproach.”).

Per Air Mail: “Bright Lights, Big City made McInerney, then an M.F.A. student at Syracuse University, famous…It’s written in the second person, a point of view McInerney chose because ‘that is how you speak to yourself.’” The prose maintains a rhythmic musicality, a sense of immediacy cultivated by its author’s chosen perspective — and his use of present tense…Pulling from his own life, McInerney curates a particular picture of his narrator’s depression, of its causes, before widening the aperture of his authorial lens. This shift reframes the reality of the novel in its final pages, establishing the second-person perspective as a form of dissociation. In a 2016 piece for The Guardian, McInerney reflects: “The story was informed by the pain and misery of the events of the previous year, and yet somehow that voice gave it a kind of comic lift, a wry perspective on the protagonist’s downward spiral. The narrator’s falling apart, but he’s watching himself do so, and commenting upon it with some degree of objectivity.”

The Talented Mr. Ripley by Patricia Highsmith (1955) — Highsmith’s novel adopts a close third-person point of view, inhabiting the paranoid and particular mind of Tom Ripley (“Tom had imagined horrible things during the boat trip: Marge beating him to Palermo by plane, Marge leaving a message for him at the Hotel Palma that she would arrive on the next boat. He had even looked for Marge on the boat when he got aboard in Naples”). It begins with a jolt, as Highsmith writes: “Tom glanced behind him and saw the man coming out of the Green Cage, heading his way. Tom walked faster. There was no doubt the man was after him. Tom had noticed him five minutes ago, eyeing him carefully from a table, as if he weren’t quite sure, but almost. He had looked sure enough for Tom to down his drink in a hurry, pay and get out.” These opening lines create a kind of kinship between Tom and the reader, mimic the feeling of a hot pursuit experienced in parallel.

“The man coming out of the Green Cage” emerges as shipping magnate Herbert Greenleaf. To bring his son, Dickie, back to the United States, he recruits Tom to travel to Italy on his dime in a desperate attempt at persuasion. Upon arrival, Tom immediately gets off task (“Another week went by, of ideally pleasant weather, ideally lazy days in which Tom’s greatest physical exertion was climbing the stone steps from the beach every afternoon and his greatest mental effort trying to chat in Italian with Fausto, the twenty-three-year-old Italian boy whom Dickie had found in the village and had engaged to come three times a week to give Tom Italian lessons”). He befriends Dickie and his pseudo-girlfriend, Marge, living out an idyllic seaside life on Mongibello — until jealousy and rage come to consume him.

Ripley Under Ground by Patricia Highsmith (1970) — Patricia Highsmith’s art world-immersed follow-up to The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955) picks up a few years after Tom Ripley’s narrow escape from shouldering his rightful blame for Dickie Greenleaf’s death. In Ripley Under Ground (1970), the novel’s eponymous sociopath has married French pharmaceutical heiress Heloise and resides at their country estate, Belle Ombre. Heloise’s allowance couples with Dickie’s fortune to fund their lifestyle, with additional earnings coming from The Buckmaster Gallery in London.

The background on Buckmaster: Years ago, British painter Philip Derwatt disappears after committing suicide in Greece, leaving his friends and the masterminds behind The Buckmaster Gallery — photographer Jeff Constant and journalist Ed Banbury — to sell his remaining paintings. Their publicity efforts lead Derwatt’s notoriety to skyrocket. Tom, nervous about his long-term ability to live on his earnings from Dickie’s death, concocts a forgery scheme in exchange for 10% of the gallery’s profit. With Tom’s guidance, the group spins a false tale about the British painter’s survival and subsequent relocation to Mexico, bringing in Derwatt disciple Bernard Tufts to forge new works.

Ripley Under Ground opens with Derwatt Ltd. as an unshakeable economic engine — until American collector Tom Murchison raises concerns about the authenticity of one of his Derwatts. He zeroes in on the painter’s usage of certain purples, a reversal of technique that strikes him as odd. This uncertainty catapults the novel’s narrative, propels a twisty sequence of events as gripping as the one that defines its predecessor.

The Friday Afternoon Club: A Family Memoir by Griffin Dunne (2024) — The Friday Afternoon Club (2024) is filled with wild anecdotes. Dunne lives a kind of Forrest Gumpian existence, with famous figures flitting in and out of some of his most formative moments…Each celebrity story serves a purpose, contextualizes the world that Dunne and his family inhabited. The memoir maintains a tone of self depreciation that, to me, makes it incredibly readable; in her review for The New York Times, Alexandra Jacobs rightly identifies that that Dunne “has a gingerly attitude toward fame, having witnessed its costs firsthand.”

While Part One of The Friday Afternoon Club recounts Dunne’s winding road toward his starring role in Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (1985), with the narrative threads of his family’s stories interwoven throughout it, Part Two centers on [his sister] Dominique’s murder trial. Her killer, ex-boyfriend and Ma Maison sous chef John Sweeney, ultimately served only three years in prison for strangling her to death after the judge bungled the trial process, pushed the jury out of the room during key testimonials that proved Sweeney’s track record of violence against women.

In my review of Sloane Crosley’s new memoir, Grief Is for People (2024), I discuss how “Crosley decries authors who write ‘not ‘I miss this person,’ but ‘Miss this person as I do,’’ as ‘too much laundering of empathy.’” Dunne, like Crosley, avoids “laundering empathy” by breathing life into his now-deceased family, capturing the specific texture of their quirks. In The Friday Afternoon Club’s acknowledgments, he writes: “Alex is the only surviving member of my immediate family, but if it’s possible to acknowledge the dead, I want to thank my parents, Dominique, John, Joan, and Quintana for letting me bring them to life in my office each day as I wrote. Their presence was so vivid that the pictures of them on my corkboard actually shimmered with light. When my work on the book was complete, I mourned their losses all over again.”

Very Cold People by Sarah Manguso (2022) — A haunting meditation on girlhood, Very Cold People (2022) enlivens Waitsfield, Massachusetts from the first-person perspective of Ruthie, a Jewish Italian girlie trying to make sense of the frozen town that raised her (“My own girlhood felt like something from 1650 even when it was happening. The little parties, kindnesses done by friends, the light as I walked home from school. Pine needles. I spent those days feeling half-there, not quite committed to that life.”). Told in brief vignettes by an adult Ruthie, this rhythmic read looks back on the web of friendships, of local myths, of family scars that came to comprise her childhood. Manguso implements a kaleidoscopic lens at points, hindsight afforded by Ruthie’s age that slowly reveals the dismal fates of her peers. Abuse bubbles beneath Manguso’s nostalgic, pared-back prose, becoming overt only toward the novel’s end.

White Out: The Secret Life of Heroin by Michael Clune (2013) — With White Out (2013), Clune crafts an immersive memoir that feels like fiction — “enlivening, surprising, and gripping.” He opens by explaining: “My past is infected. I have a memory disease. It grips me through what I can remember. For example, seven years ago in Baltimore, Cat wakes me up to kiss me on her way to work. I’m about to fall back asleep when I remember about Dominic. I remember how fun he can be. I sit up in bed and think about it.” These opening lines collapse linear time, establish the poetic flatness that goes on to shape the book. For instance, one of the most memorable sequences traces Clune’s childhood search for a real-life Candy Land, a pursuit lyrically wrenched into the memory of his first time using. Traditional notions of past and present shatter, and all the stories swirl into one.

Highway Thirteen by Fiona McFarlane (2024) — Fiona McFarlane opens her new short story collection with an epigraph from William Shakespeare’s Richard II (1595): “Each substance of a grief hath twenty shadows.” Highway Thirteen (2024) then continues with a glimpse into twelve such shadows of grief, distinctive stories spanning from 1950 through 2028, from Bristol to Austin to Sydney. Each narrative strand connects to a string of serial killings in 1990s Australia, loosely based on Ivan Milat’s 1989 reign of terror. Forms vary, from first to third person, from traditional prose to mock podcast script. As Kirkus Reviews describes: “The criminal investigation never becomes the central plot; the killer himself, here called Paul Biga, remains offstage while his victims appear only in fleeting mentions or glimpses.”

Honorable Mentions (in no particular order): Here in the Dark by Alexis Soloski (2023), The Best of Everything by Rona Jaffe (1958), So Late in the Day: Stories of Women and Men by Claire Keegan (2024), Cocktails with George and Martha: Movies, Marriage, and the Making of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? by Philip Gefter (2024), Neighbors and Other Stories by Diane Oliver (2022), Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? by Edward Albee (1962), Grief Is for People by Sloane Crosley (2024), The Body in Question by Jill Ciment (2019), Last Summer in the City by Gianfranco Calligarich (1970), Ripley’s Game by Patricia Highsmith (1974), Liars by Sarah Manguso (2024), Ripley Under Water by Patricia Highsmith (1991), Strangers on a Train by Patricia Highsmith (1950), Intermezzo by Sally Rooney (2024), Is Mother Dead by Vigdis Hjorth (2022)

While we’re on the topic of 2024 favorites…

Top Movies of 2024

Once again, I am not using quality as a solitary ranking tool here, though, of course, it serves as a factor; I’m simply creating this list from the films I had the best time watching, again pulling excerpts from my past reviews to reveal the rationale.

Here we go:

The Conversation (1974, dir. Francis Ford Coppola) — I texted half my contact list upon leaving The Paris Theater’s screening of this film, urging them to watch it on Netflix immediately. To quote the randos on Letterboxd:

“Catholic wiretapper; forgotten profession”

“Every scene in this movie I go ‘oh this is my favorite part’”

“fuses my two favorite things: jazz and worrying”

SO true.

Coppola’s neo-noir thriller opens over a bustling Union Square in San Francisco. Jazz hums and bleeds into garbled audio. The image becomes clearer. Filmed documentary-style, a couple (played by Cindy Williams and Frederic Forrest) weaves in and out of the frame, between mimes, musicians, hedges. Bits of their conversation — the conversation — crash over, fade behind, the sounds of the square. Their state of surveillance becomes apparent, a job at the hands of expert wiretapper Harry Caul (played brilliantly by Gene Hackman). The narrative unravels from, loops back to, this point, as Harry, faced with delivering the tapes to to an executive known as “the Director” (played by Robert Duvall), begins to fear for the couple’s life.

Before Sunrise (1995, dir. Richard Linklater) — A meditation on time, Before Sunrise (1995) opens on a Eurail train from Budapest with two young people heading in divergent directions. While French Sorbonne student Céline (played by Julie Delpy) travels back home to Paris after visiting her grandmother, Texan tourist Jesse (played by a stupidly sexy Ethan Hawke) gets ready to wind down his European travel in Vienna. After striking up a conversation with her on the train, Jesse convinces Céline to disembark with him in Vienna. She complies, kicking off what I would classify as the most engrossing hour and 45 minutes of nonstop conversation ever captured on film. They spend the night wandering the city before Jesse’s early morning flight back to the United States, progressing through a series of encounters made mesmerizing by the film’s clever script, as well as Hawke and Delpy’s electric chemistry.

Anora (2024, dir. Sean Baker) — Pretty Woman (1990) meets After Hours (1985), Sean Baker’s latest film inhabits Brooklyn’s Eastern European-dominant community of Brighton Beach. The narrative centers on Anora “Ani” Mikheev (played by Mikey Madison), a tough-talking twenty-three year-old stripper at a Midtown club. When a customer requests a Russian-speaking dancer, Ani gets introduced to Ivan “Vanya” Zakharov (played by Mark Eydelshteyn), the hard partying 21-year-old son of a Russian oligarch. The pair gets sucked into a whirlwind romance, complete with day after day languishing in Ivan’s Brighton Beach mansion and a joyride to Vegas. But their sexual and domestic bubble bursts with the arrival of Toros (played by Karren Karagulian), Garnick (played by Vache Tovmasyan), and Igor (played by Yura Borisov), a trio of henchmen sent by Ivan’s father, launching Ani on an odyssey through and beyond Brooklyn. As Patrick Gibbs writes in his Slug Mag review: “Nothing about this story…should be humorous, yet most of Anora is a fast and furious comedy that borders on screwball farce.”

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964, dir. Jacques Demy) — Winner of the Palme d'Or, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) centers on a pair of young lovers residing in the rural French town of Cherbourg. 17-year-old Geneviève (played by Catherine Deneuve) works alongside her mother, Madame Émery (played by Anne Vernon), at their struggling umbrella boutique, while Guy (played by Nino Castelnuovo), an auto mechanic, cares for his sickly aunt and godmother, Élise (played by Mireille Perrey). Geneviève and Guy spend their evenings exploring the town, fantasizing about a life together, a marriage, despite her mother’s protestations. But before they can exchange vows, Guy gets drafted to Algeria, leading to a separation that draws into question the longevity of first love.

The plot has the potential to edge into melodrama, but Deneuve and Castelnuovo ground the film, as does Demy’s downbeat, reflective ending. As Roger Ebert writes in his 2004 review, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg “was a curious experiment in which all of the words were sung; Michel Legrand wrote the wall-to-wall score, which includes not only the famous main theme and other songs, but also Demy’s sung dialogue, in the style of the lines used to link passages in opera. This style would seem to suggest a work of featherweight romanticism, but Umbrellas is unexpectedly sad and wise, a bittersweet reflection on the way true love sometimes does not (and perhaps should not) conquer all.”

Before Sunset (2004, dir. Richard Linklater) — Before Sunset (2004) picks up where its predecessor left off — sort of. Jesse (played by a still stupidly sexy Ethan Hawke) reads the closing excerpt from his novel, This Time, a fictional retelling of the first film, at Shakespeare and Company in Paris. As he fields questions about whether the lovers meet again, Jesse notices Céline (played by Julie Delpy) watching his reading from the next room. The pair leaves the bookshop together and embarks on a walk around Paris, the kind of banter-laden stroll fans of the trilogy have come to expect. Linklater once again leverages long, uninterrupted takes to create a sense of verisimilitude, to simulate the illusion of an audience eavesdropping over the course of 80 minutes.

Released nine years after Before Sunrise (1995), Before Sunset carries markers of the passage of time — or, as my boy Roger Ebert puts it, “continues the conversation that began in Before Sunrise but at a riskier level.” Its actors have aged along with their characters, and their characters bear more baggage, the complications of death and marriage and children that remained in the first film’s future tense. Their conversations — adorned more prominently with despair — reflect this weight. Ebert continues: “They lead up to personal details very delicately; at the beginning they talk politely and in abstractions, edging around the topics we (and they) want answers to: Is either one married? Are they happy? Do they still feel that deep attraction? Were they intended to spend their lives together?”

Maria (2024, dir. Pablo Larraín) — This biopic from Chilean filmmaker Pablo Larraín marks the third in his series about iconic 20th Century women, with Jackie (2016) and Spencer (2021) as its predecessors. The film follows the final week in the life of Maria Callas (played by Angelina Jolie “in a queenly performance of poise and mystique,” per Tomris Laffly for Roger Ebert.com), the famed Greek opera singer who retreated from performance and public life in her final years.

Certain critics have decried the movie’s more theatrical elements, but, from my perspective, the kinds of sequences that feel sensationalized in Spencer (2021) land here. Each flare reflects the emotional quality of opera and, more importantly, Callas’s deteriorating sense of her surroundings. Her chosen cocktail of pills causes hallucinations, and various figures — from her sister, Yakinthi, to Onassis — float through the frame, their status as truth or illusion tenuous. Laffly continues: “While her end is inevitable in the film — Callas died in 1977 at the young age of 53 — you will be disarmed, even moved to tears, experiencing Larraín’s care for her in Maria, which is essentially a compassionate ghost story on the beloved things we lose, as they continue to deteriorate and slip through our fingers against our will.”

Cape Fear (1962, dir. J. Lee Thompson) — Wow, Robert Mitchum is genuinely terrifying in this movie. As Variety put it back in 1962: “Wearing a Panama fedora and chomping a cocky cigar, the menace of his visage has the hiss of a poised snake.”

This psychological thriller centers on lawyer Sam Bowden (played by Gregory Peck), who testified in an attempted rape case eight years prior to the start of the film. His testimony put defendant Max Cady (played by Mitchum) away, but, now, the time has come for his release. Blaming Sam for his imprisonment, Max vows revenge; he begins to stalk and subtly threaten Sam and his family, including his wife, Peggy (played by Polly Bergen), and his 14-year-old daughter, Nancy (played by Lori Martin). As Sam struggles to prove the danger Max poses to the authorities, the narrative coalesces in a chilling denouement.

A Complete Unknown (2024, dir. James Mangold) — From the filmmaker behind Walk the Line (2005), A Complete Unknown (2024) opens with 19-year-old Bob Dylan (played by Chalamet) arriving in New York to bid farewell to one of his heroes, hospitalized folk star Woody Guthrie (played by Scoot McNairy). The film then traces Dylan’s rise to fame within the confines of the folk community, followed by his rejection of it at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, where he famously went electric. It simultaneously reanimates his relationships with Suze Rotolo, renamed Sylvie Russo at Dylan’s behest (played by Elle Fanning), and Joan Baez (played by Monica Barbaro).

In the film, Dylan tells Sylvie: “If anyone is gonna hold your attention on a stage, you have to kind of be a freak…You can be beautiful or you can be ugly, but you can’t be plain.” Chalamet takes this principle to heart. He accentuates the idiosyncrasies that define Dylan without strapping into the straightjacket of imitation; he embodies the seminal artist’s singing and speaking voices, as well as his mannerisms, while still bringing freedom and flexibility to his performance. As James T. Keane writes in his piece, “A Bob Dylan Nerd Reviews A Complete Unknown” (lol), “Chalamet captures well the Dylan of that period: alternately charming and vicious, Everyman but then Mephisto.”

Perfect Days (2023, dir. Wim Wenders) — A co-production between Japan and Germany, Perfect Days (2023) chronicles a series of days in the life of Tokyo public toilet cleaner and Taurus-coded king Hirayama (played by Kōji Yakusho). Hirayama collects cassette tapes that are Extremely Aligned with my Musical Taste (Patti Smith, Lou Reed, The Kinks, The Velvet Underground, etc.), reads authors ranging from William Faulkner to Aya Kōda. His daily routine includes tending to plants and photographing trees, as well as meticulously scrubbing every toilet in Tokyo’s Shibuya ward. He draws not only immense pleasure from music, literature, and nature, but also satisfaction from his work.

The film adopts a cyclical narrative. Variants — from Takashi’s friend, Aya (played by Aoi Yamada), to Hirayama’s niece, Niko (played by Arisa Nakano) — float in and out of a schedule as it repeats. These people, these punctures in the pattern, shed light on Hirayama’s past and present, reveal the contours that shape his selfhood; slowly, methodically, a complete picture comes into view.

Challengers (2024, dir. Luca Guadagnino) — “Now, that’s cinema, baby !!!” -me to five different friends after leaving my screening of Challengers (2024) at Village East

In case you’ve been living under a rock, this tennis throuple movie from Call Me By Your Name (2017) director Luca Guadagnino traces the decade plus-long love triangle between rising tennis star-turned-coach Tashi Duncan (played by Zendaya), tennis pro Art Donaldson (played by Mike Faist), and B-tier player Patrick Zweig (played by my king, Josh O’Connor). The narrative coalesces around a match between Art and Patrick at the ATP Challenger Tour in New Rochelle, but not before a mid-aughts look back at the story behind their relationships to Tashi — and each other.

Honorable Mentions (in no particular order): The Long Goodbye (1973), Tótem (2023), Dressed to Kill (1980), Anatomy of a Fall (2023), The Holdovers (2023), The Zone of Interest (2023), Killers of the Flower Moon (2023), Rope (1948), What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962), Eno (2024), Scream 2 (1997), The Substance (2024), In the Cut (2003), Wicked (2024), Jackie (2016)

Upcoming Content to Consume

Syndicated BK: When Harry Met Sally (1989) and Phantom Thread (2017) New Year’s Day Double Feature (Date: 1.1) — Ring in 2025 with a New Year’s Day double feature tonight! As I write in the December newsletter: “For those of you unfamiliar, the Nora Ephron classic…asks the age-old question: Girls and gays aside, can men and women really be friends? Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan star as Harry Burns and Sally Albright, a pair of acquaintances-turned-friends whose lives converge and diverge over a 12-year period, with the narrative coalescing to a crescendo in the final hour of 1988.” Meanwhile, Phantom Thread (2017), a period piece from Paul Thomas Anderson I have yet to see, tells “the wrenching tale of a woman's love for a man and a man's love for his work,” per The New York Times, and similarly features a memorable New Year’s Eve scene.

Film Forum: Mr. Deeds Goes to Town (1936) (Dates: 1.1-1.2) — Gary Cooper as a sexy socialist himbo! I had the pleasure of ringing in 2025 with a screening of this movie at Film Forum last night and cannot recommend it enough.

Full thoughts to come in the January Movie Review, so, in the meantime, per the site: “Gary Cooper’s ‘pixilated’ tuba-playing, greeting card versifying Vermonter Longfellow Deeds inherits $20 million — and then he’s whisked from Mandrake Falls to Park Avenue, as wisecracking reporter Jean Arthur dubs him the ‘Cinderella Man.’” In The Story of Cinema (1985), David Shipman dubs this Frank Capra film the best and most representative of the 1930s. Catch it at Film Form through tomorrow!

The Paris Theater: Jackie (2016) (Dates: 1.1-1.2) — You also can spend today and tomorrow at The Paris Theater checking out Pablo Larraín’s Jackie Kennedy biopic as part of a series dedicated to the Chilean director’s work, timed to play in tandem with the theatrical run of his latest film, Maria (2024).

I watched Jackie (2016) and Maria back to back last month. As I discuss in the November Book Review, the earlier film “traces the actions of Jackie Kennedy (played by Natalie Portman) in the week immediately following her husband’s assassination. As writer and critic Richard Lawson writes in a 2016 Vanity Fair piece: ‘Looping and dizzy, sad and intimate…Jackie is an odd, artful psychological study, one that blends stony seriousness with whispers of camp…Portman doesn’t do an exact imitation of Jackie’s birdy, breathy affectations, her curling downspeak at the end of sentences. But she does something that’s smartly evocative of it, while also delivering a compellingly modulated performance beyond all the mechanics of voice and bearing. In [Pablo] Larraín’s watchful aesthetic, Portman’s intensity works rather perfectly — together they create something transfixing, a film that washes over you as it loops and lingers.’”

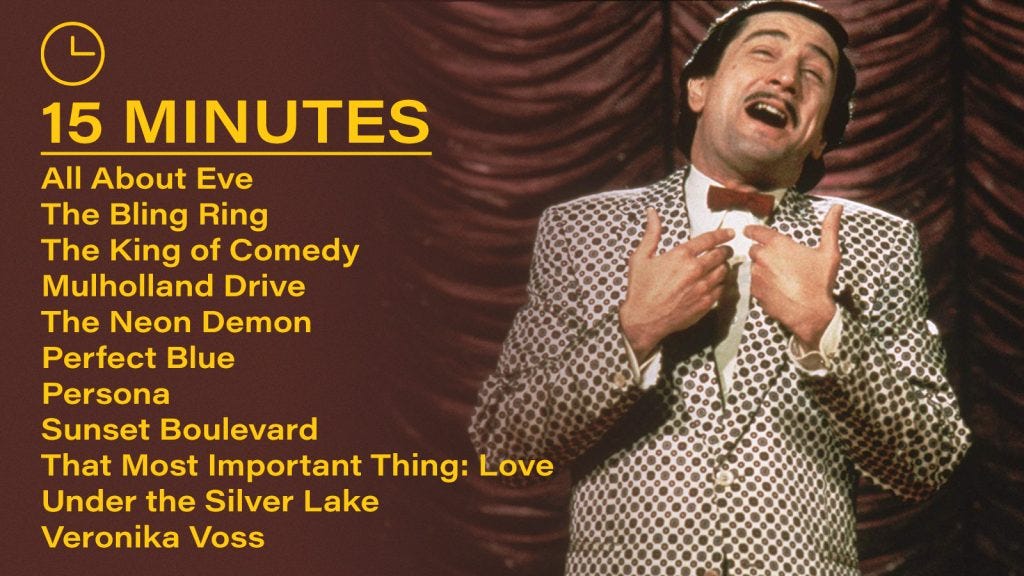

Metrograph’s 15 Minutes Series (Opening Date: 1.3) — This upcoming series from Metrograph features a line-up of films about fame and the foibles that define those people seeking it.

Per the site: “The lure of fame, fame, fatal fame does terrible things to the characters in this series: cracked individuals who will do anything to claw their way into the spotlight, or back into it, from the aging divas of Sunset Boulevard (1950) and Veronika Voss (1982) to the reality-challenged, celebrity-fixated, sociopaths of The Bling Ring (2013) and The King of Comedy (1982). Taking its title from Andy Warhol’s much-repeated prophecy, 15 Minutes brings together films — from David Lynch, Andrzej Żuławski, Ingmar Bergman, and other titans of world cinema — whose starstruck protagonists are led by something like the dictum of Robert De Niro’s delusional would-be standup Rupert Pupkin: ‘Better to be king for a night than schmuck for a lifetime!’”

My favorite films in the line-up include Sunset Boulevard, All About Eve (1950), and Mulholland Drive (2001). Only certain screening times appear available right now, so you can check back for more details here!

Metrograph’s The Many Lives of Laura Dern Series (Opening Date: 1.4) — A series that requires no introduction! Metrograph will launch a program dedicated to cult-favorite leading lady Laura Dern this month.

My favorites slated for screening include Blue Velvet (1986), Wild at Heart (1990), and Marriage Story (2019). Much like the 15 Minutes series, only certain showtimes appear available right now, so you can check back for more details here!

The Center for Fiction: John Cheever’s “The Swimmer” (1964) with Pam Newton (Date: 1.7) — A summer tale for a chilly winter night! This event, happening from 6:30 to 8:00 PM on 1.7, will include drinks and a discussion of John Cheever’s 1964 “The Swimmer,” a source of inspiration for Emma Cline’s The Guest (2023), arguably the novel of summer 2023. Cline tells Interview Magazine: “This John Cheever short story…ends in such a bizarre desperate, haunting way, to me that’s like a horror story, a story where you’re estranged from your own life, everyone you love is gone, you can’t account for how you got so far into the woods. There’s something just so devastating about it.”

As I write in the inaugural newsletter, “The Swimmer” “feels like floating down a river on a hot summer day. We follow a drunken gentleman, a husband and father, as he wanders in and out of his neighbors’ pools, through the yards of his peers. Darkness slips in and out of the frame as our unreliable narrator continues his quest to swim across the ‘string of swimming pools…[the] quasi-subterranean stream that curves across the county’ — until it finally short circuits the picture.”

Yale English Professor Pam Newton will facilitate this conversation at The Center for Fiction; I joined her discussion of Leo Tolstoy’s “Master and Man” (1895) last winter, and she did a nice job moderating. Registration costs $50 and includes beer, wine, coffee, or a cocktail. Attendees will receive a PDF copy of the story via email!

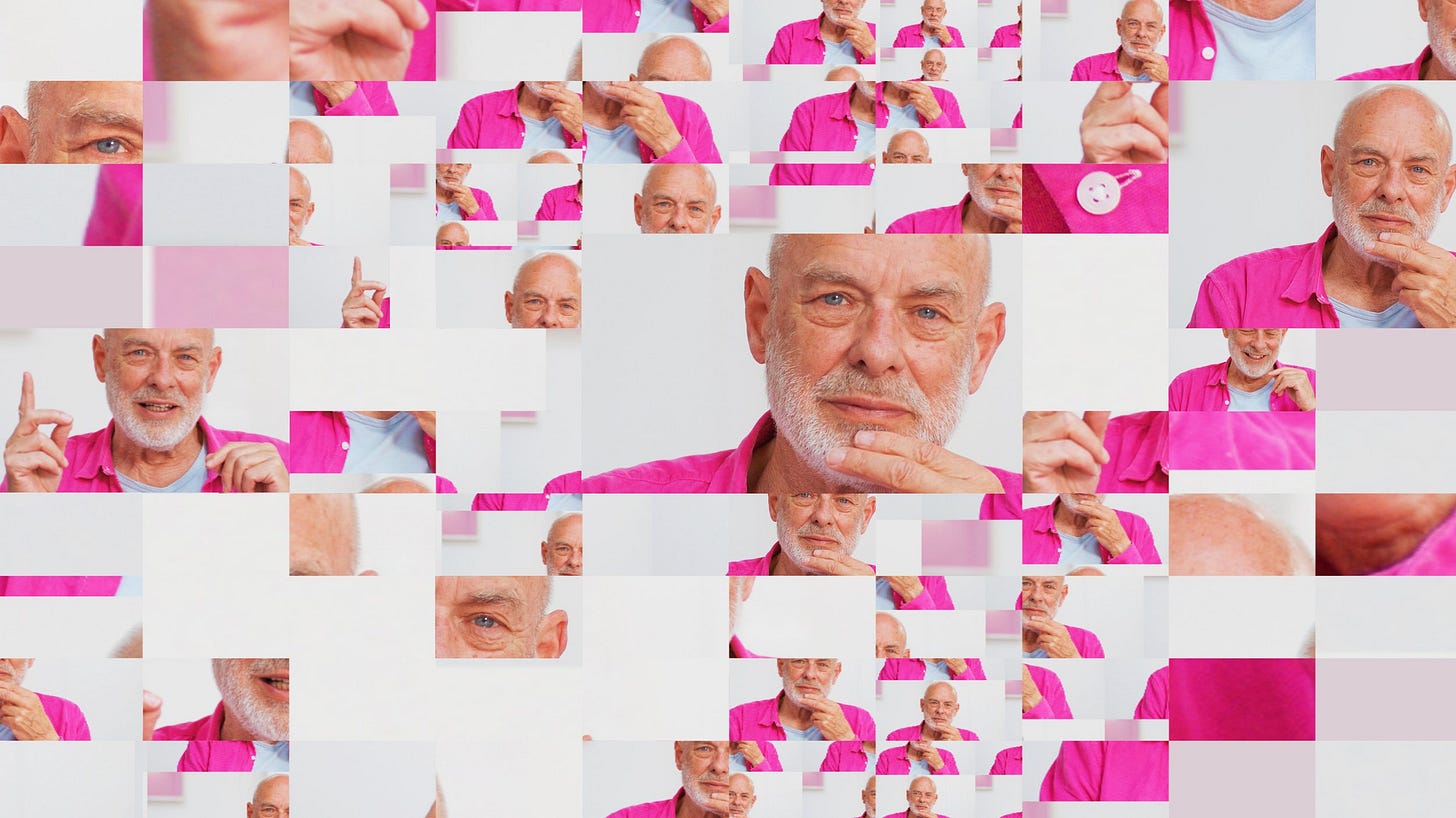

Roxy Cinema and Village East: Eno (2024) (Dates: 1.3-1.9) — Gary Hustwit’s Brian Eno documentary makes a return to theaters this month with a brief run at Village East and The Roxy! Eno (2024) consists of various vignettes tied to Gen X god and Roxy Music frontman Brian Eno’s life, their presentation dependent on a computer program that live edits the film so a different version plays at each screening. As I discuss in the July Movie Review:

The structure of the documentary…emerges as the filmic equivalent of Eno’s experimental approach to music-making. (ICYMI: Eno considers himself a generative musician, one who believes in creating “a system or a set of rules which, once set in motion, will create music for you.”) The friend I went to this film with in July revisited it in August and saw an entirely different version. Per The New York Times, Hurstwit’s “collaborator, the digital artist and programmer Brendan Dawes, explained that because of the variables, including 30 hours of interviews with Eno and 500 hours of film from his personal archive, there are 52 quintillion possible versions of the movie. (A quintillion is a billion billion.)”

Within each version of the film, certain vignettes recur, while others appear only once. Hustwit and Dawes flatten the importance of the various events that comprise Eno’s life, creating a perpetual present tense that echoes the musician’s insistence that: “I don't live in the past at all; I'm always wanting to do something new. I make a point of constantly trying to forget and get things out of my mind.”

You can check out showtimes at The Roxy here and Village East here. I’d recommend going to the 7:40 PM screening on 1.4 at Village East, which includes a Q&A between Hustwit and documentary filmmaker Kirsten Johnson after the show!

New Beverly Cinema: Cool Hand Luke (1967) (Dates: 1.23-1.24) — Paul Newman at his finest! Cool Hand Luke (1967) centers on Luke Jackson (played by Newman), a petty criminal sentenced to two years in a Florida prison. Luke refuses to surrender to authority, even as it begins to eat away at him physically and mentally.

As Roger Ebert writes in his 1967 review: “Newman brings this character to the end of its logical development, playing a hero who becomes an anti-hero…He’s the only prisoner with guts enough to talk back to the bosses and the only one with nerve enough to escape. He begins the movie as a likable enough guy, always smiling, always ready for a little fun. He eats 50 hard-boiled eggs on a bet and collects all the money in the camp…When Luke finally does escape for the last time, he isn’t smiling so much.”

Cool Hand Luke, as I see it, reflects and foretells the anti-establishment tone of New Hollywood that reaches a fever pitch with Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Chinatown (1974), and Taxi Driver (1976), among other seminal films of the 1970s and late 1960s.

Miscellaneous Musings

Lauren Groff on Her Creative Process — Nearly 20 years ago, novelist Lauren Groff famously agreed to move to Florida to support her husband’s career on the grounds that he manage their children’s morning routine, allowing her time to write first thing when she wakes up (“Just because I’m in the house doesn’t mean that I’m available.”). In a recent interview with The Creative Independent, Groff discusses how she makes use of that writing time in the broader framework of her OCD, how she tricks herself “in specific, very structured ways” to ensure productivity. OCD makes everything — from thoughts to projects — difficult to dismiss. Groff reveals how extracting freedom from the confines of structure allows her to embrace the dead space that defines artistry.

Groff reflects: “I think fallow periods are necessary for all fields. So, instead of writing poorly I’m reading beautifully, and the reading is part of the writing too. I don’t feel like I’m being unproductive because I’m still dreaming into the space where books come. So, I’m not being productive at all whatsoever and I haven’t been in a couple of years, but it doesn’t matter. I’m still a writer and I know that one day, it’ll come back or it won’t. That’ll be fine too because I’m still doing the work.” She then goes on to explain how she determines when to set a project aside, saying: “It’s paying attention to the energy of the piece. If it feels really distant from me, I know that there’s an irreconcilable problem between me and the work, and I need to just put it to the side until it wants to come back to me…It’s really allowing the work not to just be the work at hand, but the longer process of making something, making a life and making a life in art.”

Based on her experience judging the O. Henry Prize and editing The Best American Short Stories (2024), Groff also observes a massive shift toward first-person perspectives in contemporary fiction. She connects this abandonment of the third person to lack of trust in authority, explaining: “I had a hard time [selecting pieces for the O. Henry Prize] because out of 120 [stories that were sent to me, about 90 of them] were in the first person, which was an overwhelming number of first person stories. I think it’s because of the loss of our faith and authority in 2024. I mean, as media outlets are disintegrating, religion is showing its ugly themes, all sorts of larger structures, we’re just collectively losing faith in them. I think that the one place of authority is the self…The vast majority of stories being written now are being written out of the self, and I’m sorry, self is so limited. I mean, the third person exists as this magisterial god’s eye for a reason, and you can do a lot more of it, I think, especially in the confines of the short story.”

McNally Editions “What Kind of Reader Are You?” Quiz — McNally Editions has unveiled an entertaining new quiz that reveals what type of reader you are, providing book suggestions from the imprint’s collection of reissued works based on your results.

The quiz sorts readers into three categories: The Escape Artist, The Realist, and The Decadent. Per McNally Editions: “Imaginative, empathic, ever-so slightly obsessive, the escape artist is capable of disappearing for hours inside the mind of a favorite author…Discerning, cosmopolitan, fascinated by history and changes in intellectual fashion, the realist loves a novel that holds a mirror up to its era…Sophisticated, curious, hard to shock, the decadent takes a refined pleasure in the many varieties of human nature, even at its most extreme.” My friends and I had fun comparing and discussing our types! (Mine was The Escape Artist.)

Take the quiz here!

Supplemental Reading

As always, don’t forget to use archive.ph if you can’t access these pieces or any of the ones throughout my Substack!

Rolling Stone: Who Was Suze Rotolo, the Inspiration for Elle Fanning’s Character in A Complete Unknown?

New York Times: What Really Happened the Night Dylan Went Electric?

From the Desk of Marlowe Granados: Owning a Piece of The Last Days of Disco (1998)

The Paris Review: Jhumpa Lahiri, The Art of Fiction No. 262

New York Times: Is Mikhail Baryshnikov the Last of the Highbrow Superstars?

Thinking About Getting Into: Can there ever be another Baryshnikov?

Social Media Round-Up

A section aggregating tweets, TikToks, Notes, etc. that made me laugh in the past month:

Cocktail of the Month

This January, warm up with whiskey by making the…

Add a half teaspoon of brown sugar, three or four dashes of black walnut bitters, and two ounces of your whiskey of choice (I personally prefer bourbon) to an ice-filled mixing glass. Stir for 30 seconds, or until the drink properly chills and dilutes.

Strain the drink into a lowball glass over a large ice cube. Slice off an orange peel and twist it over the glass. Finally, put the orange peel on top of the ice cube, and enjoy!

That’s all for now! Stay tuned for the December Book Review.

xo,

Najet