So, this month I watched both Cape Fears and The Long Goodbye (people think Elliott Gould is hot, right?). I also cried through 70% of Tótem.

Let’s get into it:

Cape Fear (1962, dir. J. Lee Thompson) — Wow, Robert Mitchum is genuinely terrifying in this movie. As Variety put it back in 1962: “Wearing a Panama fedora and chomping a cocky cigar, the menace of his visage has the hiss of a poised snake.”

This psychological thriller centers on lawyer Sam Bowden (played by Gregory Peck), who testified in an attempted rape case eight years prior to the start of the film. His testimony put defendant Max Cady (played by Mitchum) away, but, now, the time has come for his release. Blaming Sam for his imprisonment, Max vows revenge; he begins to stalk and subtly threaten Sam and his family, including his wife, Peggy (played by Polly Bergen), and his 14-year-old daughter, Nancy (played by Lori Martin). As Sam struggles to prove the danger Max poses to the authorities, the narrative coalesces in a chilling denouement.

Cape Fear (1962), at its core, captures the specific flavor of psychological torture that characterizes anxiety. While Scorsese’s 1991 reboot (more on that in a minute) edges into the realm of pure horror, the 1962 version belongs to the tradition of film noir, a canon predicated on uncertainty. It bears narrative and aesthetic similarities to Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt (1943). On a narrative level, Cape Fear (1962) captures the threat of violence without proof, its impact on an archetypal American family, through its villain’s “menacing omnipresence.” From an aesthetic perspective, Thompson juxtaposes closely cropped and wide-set shots; without spoiling specifics, this tension builds suspense most memorably, for me, in a sequence that features Nancy running through her school.

Speaking of Hitchcock, Psycho (1960) composer Bernard Herrmann scored Cape Fear (1962), relying on a similar strings-based symphony. As Stephen C. Smith writes in his 2002 book, A Heart at Fire's Center: The Life and Music of Bernard Herrmann: “Herrmann's score reinforces Cape Fear's savagery. [His] prelude searingly establishes the dramatic conflict: descending and ascending chromatic voices move slowly towards each other from their opposite registers, finally crossing–just as Bowden and Cady's game of cat-and-mouse will end in deadly confrontation."

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video ($3.99)

Cape Fear (1991, dir. Martin Scorsese) — This remake of the 1962 original teases out an analogous plot through the lens of horror, a specific flavor of it that borders on carefully crafted camp.

This time around, Nick Nolte plays Sam Bowden, while Robert De Niro steps into the role of Max Cady. While the 1962 version positions Sam as a bystander, a witness to one of Max’s crimes, Cape Fear (Scorsese’s Version) transforms him into Max’s defense attorney. Nolte’s Sam occupies a more gray moral area than his 1962 counterpart, having hid key details that could have exonerated his guilty client. Meanwhile, where Mitchum’s Max instills fear through his mere presence, De Niro’s representation pursues bloodier forms of vengeance.

As a wise rando on Letterboxd put it: “Scorsese takes the original and digs into its flesh, ripping out the Hitchcockisms…and produces one of his classic wildin’ out stylistic free-for-alls that ends up some wild mix of Kafka paradox of legal frameworks and loopholes and the hothouse sexual frenzy of Tennessee Williams. The swirl of sexual violence and allure, of Sam being as much of a macho brute as Cady in his own, less demonstrative way, of women being victimized but also drawn like moths to flame, all of it exploded through Scorsese’s manic litany of techniques.” SO true.

Scorsese’s representations of Sam’s wife and daughter, to me, mark two of Scorsese’s biggest departures from his source material. While 1962’s Peggy (played by Polly Bergen) embodies the role of concerned, devoted wife, 1991’s Leigh (played by Jessica Lange) harbors more distrust in her husband, a fracture stemming from his history of infidelities. Where 1962’s Nancy (played by Lori Martin) stays rooted firmly in childhood, 1991’s Danny (played by Juliette Lewis) occupies the liminal space between child and teenager, leading to Cape Fear (Scorsese’s Version) becoming what a different Letterboxd rando rightfully calls “by far the most inappropriate film to be nominated for the MTV Movie Award for Best Kiss.”

Comparing the two films feels like an apples-to-oranges analysis in a lot of ways, each one representative of its own era and genre. While I prefer the more nuanced depiction of women, of relationships, of morality in the 1991 version, the original strikes a more poignant chord for me, in large part because of Robert Mitchum’s performance. Is De Niro good in Cape Fear (Scorsese’s Version)? Of course. But his interpretation of Max feels, in many ways, like a different shade of Taxi Driver’s Travis Bickle, a cartoonish horror villain who seems near invincible. Mitchum, on the other hand, embodies the quiet sense of impending doom that makes Cape Fear so unnerving.

This distinction impacts the terror invoked by each film’s final sequence, ultimately elevating the 1962 version above its successor for me. Mitchum’s Max deals in threats; the promise of violence drips over every word, oozes beneath each look. When the psychological peril he poses becomes physical, tension breaks, and the audience’s fear gets fulfilled. Meanwhile, De Niro’s Max deals in violence; the reality of harm emerges as his primary form of communication, coloring his boathouse battle with the Bowdens as a moment unique from each prior act only in its level of pyrotechnic absurdity.

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video ($4.29)

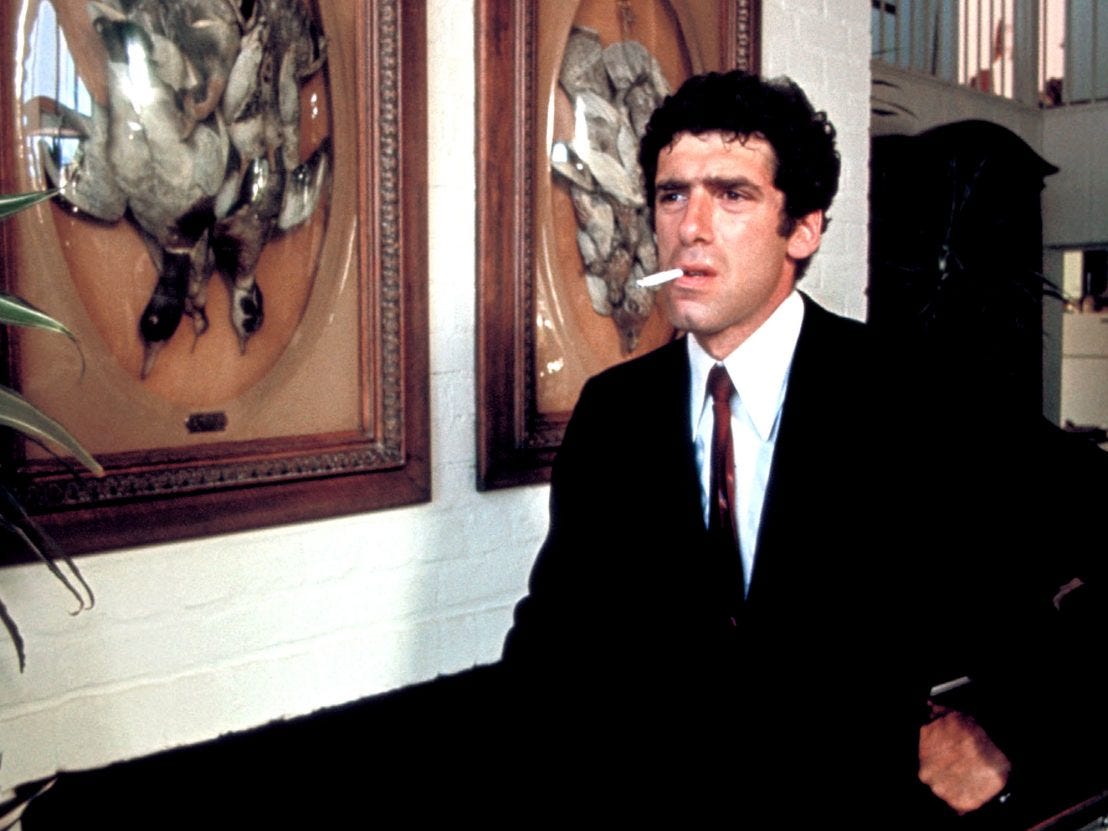

The Long Goodbye (1973, dir. Robert Altman) — To once again quote randos on Letterboxd:

“There is no surface on Earth that Elliott Gould can’t use to light a match.”

“single handedly set back the quitting smoking movement by 150 years”

“he’s so cool :)”

SO true.

Based on Raymond Chandler’s eponymous 1953 novel, The Long Goodbye takes legendary Los Angeles detective Philip Marlowe (played here by Gould, played historically by actors including Humphrey Bogart, Robert Mitchum, and James Garner) from the 1940s to the then-modern setting of the 1970s. This snarky, Seth Cohen-esque version of Marlowe lives alongside his cat in a Hollywood Hills apartment, next door to an all-female cohort of hippies. One night, he comes home from a cat food run, as one does, to find his scratched-up friend, Terry Lennox (played by Jim Bouton), in need of a ride to Tijuana. The next morning, police arrive at the apartment and reveal Terry as a suspect in the Malibu Colony murder of his wife, Sylvia, plunging Marlowe into a satirical, neo-noir search for the truth.

Per Collider: “Altman famously said of the film’s many tonal and thematic deviations from its source: ‘Chandler fans will hate my guts. I don’t give a damn.’ It’s not hard to see what he was talking about. In his film, Altman both eulogizes and ridicules the genre that Chandler helped create…Throughout the film, Marlowe drives an automobile from the ‘40s, importantly connecting him to the original era of noir. With Marlowe a stand-in for that age long gone, the disparity between his honesty and the dishonest world around him becomes a disparity between these two periods in time. The Long Goodbye of the title is not merely a reference to Lennox’s departure, but to the irretrievable, principled era of original noir.”

In satirizing its parent genre, The Long Goodbye, in many ways, declares noir dead. But, as the Collider piece rightly points out, it does so by positioning the principles of its era of inception as at odds with the then-modern world of the 1970s. This disparity, to me, feels most pronounced in how Marlowe compares to his neighbors. While he wears a suit even on the beach, the all-female cohort of hippies next door practices yoga on their porch in the nude. Their interactions consequently become a juxtaposition of new and old guards — albeit a friendly one.

The Collider piece continues: “Marlowe is established not as the commanding, hardboiled tough that Chandler wrote about, but instead as an honest and caring man. When his neighbors ask him to pick up some brownie mix on the way out for cat food, he does so without expecting compensation. Though respectable, it’s a dependability quickly revealed to be easily exploited.” Through this representational shift, Altman and screenwriter Leigh Brackett craft a version of Marlowe colored by hindsight. Seen through the lens of the present, the past becomes mythic; simpler, more straightforward. A man untainted by the moral landscape of the 1970s, Gould’s Marlowe emerges as a relic, an intentional anachronism.

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video (premium subscription)

Tótem (2023, dir. Lila Avilés) — Mexico’s shortlisted entry for the Best International Feature Oscar follows seven-year-old Sol (played by Naíma Sentíes) through a single day as she helps prepare a surprise birthday party for her gravely ill father, Tona (played by Mateo García Elizondo). As Stephanie Bunbury writes for Deadline: “Nothing in Tótem lingers, because nothing is milked for emotion. This is a film about family tragedy without a shred of sentimentality.”

The movie starts small, in the container of child and parent; Sol and her mother, Lucia (played by Lazua Larios), wholly occupy the opening sequence. Then, its world expands. Sol arrives at her grandfather’s house, and Avilés slowly introduces a tapestry of characters in the form of extended family; as the party draws nearer, chaos builds and disrupts Tona’s isolation, accentuates Sol’s loneliness. The family home emerges as a kind of character, as a site that bears witness to the present and holds knowledge of the past.

New York Times film critic Manohla Dargis observes: “As people and animals exit and enter the story — a raptor portentously flies overhead early on, part of a menagerie that includes bugs, dogs and a goldfish in a plastic bag — one aunt bakes a cake as the other dyes her hair. Avilés soon maps the house’s labyrinthine sprawl, swiftly building a tangible sense of place with precise, well-worn details and quick-sketch character portraits. Tótem is a coming into consciousness story about a child navigating realms — human and animal, spiritual and material — that exist around her like overlapping concentric circles.”

Animals and insects operate as grounding forces, anchors of calm for its youngest characters. Sol tends to snails and goldfish alike, while her younger cousin, Esther (played Saori Gurza), finds constant comfort in her cat. Avilés integrates closely cropped, enlarged shots that match the views of its child characters. This approach catapults the viewer into the dizzying perspective of the child on individual and categorical levels, an emotional journey distinguished by gradual understanding of the adult world and its perils.

Where to Watch: Film Forum

Alright, that’s it! Stay tuned for the February newsletter tomorrow.

xo,

Najet