Happy Labor Day weekend! This month, I continued reading Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley series with its second installment, while also getting introduced to an Italian answer to The Great Gatsby (1925) and the inner workings of the infamous Tilton-Beecher affair.

Let’s get into it:

Ripley Under Ground by Patricia Highsmith (1970) — Patricia Highsmith’s art world-immersed follow-up to The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955) picks up a few years after Tom Ripley’s narrow escape from shouldering his rightful blame for Dickie Greenleaf’s death. In Ripley Under Ground (1970), the novel’s eponymous sociopath has married French pharmaceutical heiress Heloise and resides at their country estate, Belle Ombre. Heloise’s allowance couples with Dickie’s fortune to fund their lifestyle, with additional earnings coming from The Buckmaster Gallery in London.

The background on Buckmaster: Years ago, British painter Philip Derwatt disappears after committing suicide in Greece, leaving his friends and the masterminds behind The Buckmaster Gallery — photographer Jeff Constant and journalist Ed Banbury — to sell his remaining paintings. Their publicity efforts lead Derwatt’s notoriety to skyrocket. Tom, nervous about his long-term ability to live on his earnings from Dickie’s death, concocts a forgery scheme in exchange for 10% of the gallery’s profit. With Tom’s guidance, the group spins a false tale about the British painter’s survival and subsequent relocation to Mexico, bringing in Derwatt disciple Bernard Tufts to forge new works.

Ripley Under Ground opens with Derwatt Ltd. as an unshakeable economic engine — until American collector Tom Murchison raises concerns about the authenticity of one of his Derwatts. He zeroes in on the painter’s usage of certain purples, a reversal of technique that strikes him as odd. This uncertainty catapults the novel’s narrative, propels a twisty sequence of events as gripping as the one that defines its predecessor. Once again, Highsmith resists the urge to compromise prose in favor of plot, cultivating a close third that catapults the reader into Tom’s psyche (“Soon, Tom was in the cocoon of the airplane, the synthetic, strapped-in atmosphere of smiling hostesses, stupid yellow and white cards to fill out, the unpleasant nearness of elbows in business suits, which made Tom twitch away.”).

The art of forgery, the mastery it requires, emerges as a primary theme throughout the novel, with Ripley and his peers repeatedly raising the question of whether a replication carries equal or greater value compared to the original. At one point, Tom asks: “‘Who knows where the line divides between Derwatt and Bernard now, frankly?’” This notion echoes and furthers an idea that emerges in The Talented Mr. Ripley, as the distinction between Tom and Dickie becomes increasingly blurred; Tom feels more at home as “Dickie” than as “Tom,” dreads a reversal toward the meek mannerisms that shape his own outward appearance.

Tom and Bernard grapple with similar sets of circumstances, reactions to their respective forgeries varying in accordance with their respective mental states and temperaments. Where Tom experiences ennui at the notion of returning to his own identity after months of posing as Dickie, guilt consumes Bernard at every turn. For instance, Highsmith writes: “Bernard was as miserable as someone, who was not an actor, trying to act on stage and hating every minute of it.” Meanwhile, Tom is, first and foremost, an actor.

In his 2012-era blog Existential Ennui, comic writer Nick Jones drives home this idea. He notes: “Highsmith professed herself very pleased with Ripley Under Ground when she finished writing the novel, and it's easy to see why. There's an unhinged, giddy, almost farcical quality to the book — a grotesque hall of mirrors, with Bernard's forging of and Tom's impersonating of Derwatt reflecting Tom's impersonation of Dickie and forging of his will in Talented. (Derwatt, Dickie...is it a coincidence that their names both begin with ‘D’...?)…Of course, Highsmith is performing the same trick she did in Talented: getting the reader to empathize and even sympathize with Tom.”

Last Summer in the City by Gianfranco Calligarich (1970) — Translated to English by Howard Curtis for the first time in 2021, this Italian novel distills a kind of midcentury listlessness that has prompted comparisons to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925) and J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye (1951). As Los Angeles Review of Books contributor Max Norman writes: “Gianfranco Calligarich’s Last Summer in the City (1970) is a slim masterpiece about a young man who moves to Rome, fails at journalism, fails at love, and ultimately fails at life. Leo Gazzara counts among literature’s great losers, an unforgettable forgettable, and Last Summer is one of those delicious minor works, enmeshed in a particular place and a particular time, that only rarely escape the confines of a national literature and onto the commercial lists of varsity American publishers. FSG’s new edition, beautifully translated by Howard Curtis, is just one of a number of new translations of Calligarich currently in the works. This new rediscovery, bigger than any before, marks the writer’s definitive entrance onto the stage of world literature.”

A true “no plot, just vibes” novel, Last Summer in the City follows its narrator, Leo, as he meanders through Rome, in and out of love, jobs, and friendships. As Call Me By Your Name author André Aciman puts it in his introduction for the new edition: “All Leo does is draft — as Arianna, his love interest, drifts; as Graziano, his drunken friend, drifts; as Fellini’s Marcello drifts. People don’t amble or stroll in Rome, they meander, and stray from the Spanish Steps to Piazza Navona, to Campo de’ Fiori, over and across Ponte Sisto to Trastevere, then back across the river to Piazza del Popolo, Via Frattina, and finally once again to Piazza di Spagna and Trinità dei Monti. Places spill into one another, by turns splendid and beautiful, then ordinary and drab, mirroring Calligarich’s masterful prose style, which frequently jolts the highly elegiac with the brutally colloquial.” Case in point, Leo narrates: “There was a different tone to her [Arianna’s] voice, but I recognized it. I would have recognized it among a thousand voices, after a thousand years, in whatever world I found myself…She was calm, without conceit, and somehow recalled the women you see in old sepia photographs. ‘How about a pick me up?’ she said. ‘I’ve quit drinking.’ [he said.] ‘Again? That makes it a vice,’ she said, walking into the bar opposite.”

In the opening pages of Last Summer in the City, Leo reflects on his grandfather’s last request, “a little seawater” on his deathbed, establishing the dichotomy between city and seaside that distinguishes the novel. Leo goes on to explain that Rome’s proximity to the ocean helped draw him to the city, introducing the ongoing odyssey — from the seaside to Rome to the seaside to Rome — that perpetually punctuates his days. He reflects: “Every day I would go to the sea. With a book in my pocket, I would take the metro to Ostia and spend most of the day reading in a little trattoria on the beach. Then I would go back to the city and hang around the Piazza Navona area, where I’d made a few friends, all of them adrift like me, intellectuals, for the most part, with the anxious but expectant look of refugees.” This split becomes especially pronounced as the book builds toward the despondency that defines its final pages (“I went in. The water was cool around my heels. I looked at the bay, the two great arms of the blurry bay in the sun. I was at the end of my tether, truth be told.”).

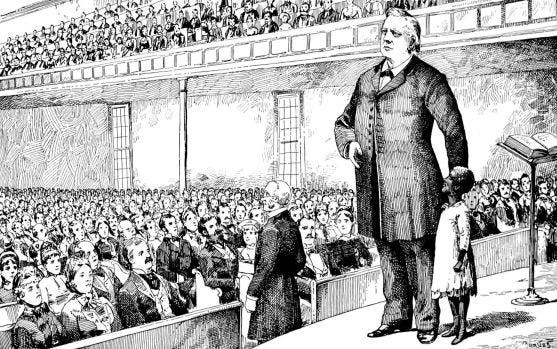

Free Love: The Story of a Great American Scandal by Robert Shaplen (1954) — 238 pages of piping hot tea, courtesy of McNally Editions. This recent reissue replicates an impressive journalistic feat undertaken by Robert Shaplen in 1953, a series of articles detailing the Tilton-Beecher affair for The New Yorker. Per the publisher, Shaplen “rel[ied] on 3,000 pages of contemporary accounts — court transcripts, love-letters, newspaper reports and illustrations, even political cartoons — to reanimate a scandal that shook the American reform movement and to expose a strand of America’s cultural DNA that remains recognizable today.”

The Tilton-Beecher affair, the adultery trial that anchors the book, operates as a 19th Century remix of the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal and the downfall of Hillsong’s Brian Houston. As the McNally Editions site details: “On the night of July 3, 1870, Elizabeth Tilton confessed to her husband that she’d had an affair with their pastor, Henry Ward Beecher. This secret would soon transfix America, for Beecher was the most famous preacher of the day, founder of the most fashionable church in Brooklyn Heights, a presidential hopeful, an influential supporter of Abolition, and a leader of the campaign for women’s suffrage. When Beecher tried to silence the Tiltons, it was a whisper network of suffragists, notably Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who spread news of the affair, and it was the radical Victoria Woodhull — an outspoken proponent of ‘free love;’ — who seized on it, as political dynamite, to blow up the myth of monogamy among the political elite.”

Shaplen distills a recognizable flavor of what Publishers Weekly calls an “American media frenzy…a vision of sweaty, prurient absurdity” that feels both of its era and timeless. He teases out the specific details that shape the trial, some of which are, simply put, silly [see: Theodore Tilton moving around picture frames (??) in the middle of the night, Elizabeth Tilton unironically signing her letters “Wifey,” Victoria Woodhull being Victoria Woodhull, etc.]. Others, however, reflect a kind of moral innocence that shapes “the way of life that revolved around Plymouth Church.” For instance, Shaplen cites a series of letters Elizabeth Tilton wrote to her husband trying to rationalize her romantic feelings for their pastor, a precursor to consummation. He observes that “the theme she constantly played upon was the figurative one of creating a cozy trinity instead of a catastrophic triangle,” distilling the kind of delusion that fuels the affair and ultimately cements Beecher’s moral immunity in the eyes of his contemporary public.

I’m almost done with Ripley’s Game (1974) and will discuss that as part of the September Book Review. In the meantime, stay tuned for the September newsletter on Sunday and all of the movie reviews that I am Extremely Behind On in the days ahead!

xo,

Najet

Love that we're both in our Ripley era - I just read that one too. Have you read The Tremor of Forgery?