Movies of the Month: June [2024]

On two thirds of Richard Linklater's Before trilogy, An American Werewolf in London (1981), and Bette Davis vs. Joan Crawford

After learning that Julie Delpy’s character does not indeed die in any of the movies, I finally started Richard Linklater’s beloved Before trilogy in June. But first, we need to discuss John Landis’s 1981 horror comedy, An American Werewolf in London.

Let’s get into it:

An American Werewolf in London (1981, dir. John Landis) — I saw this movie as part of Film Forum’s Out of the 80s Series, featuring an introduction from star Griffin Dunne. This viewing marked my second time seeing Dunne speak, as he participated in a post-film Q&A about After Hours (1985) at The Paris Theater last year. This time around, he teased the then-upcoming publication of his memoir, The Friday Afternoon Club (2024), which I reviewed as part of the June Book Review, while also shedding light on the production process behind Landis’s cult horror comedy follow-up to Animal House (1978).

An American Werewolf in London is pure fun; it’s silly, gory, and campy, as epitomized by Dunne’s depiction, Rick Baker’s monster makeup, and the movie’s soundtrack of moon-themed bangers, from “Moondance” to “Bad Moon Rising” to countless “Blue Moon” covers. The film opens with two American grad students, David (played by David Naughton) and Jack (played by Dunne), trekking across the English moors. They pull into a local pub, met with an assortment of odd townspeople who urge them to stay on the road and beware of the full moon. David and Jack continue their journey without heeding that advice. While Jack gets mauled to death, David lands in a London hospital, where he falls in love with his nurse, Alex (played by Jenny Agutter). Meanwhile, a decaying undead Jack visits David, urging his friend to kill himself before he can hurt others during the upcoming full moon.

In his lukewarm 1981 review of the film, a movie that has received more positive reception through the lens of hindsight, Roger Ebert writes: “An American Werewolf in London seems curiously unfinished, as if director John Landis spent all his energy on spectacular set pieces and then didn't want to bother with things like transitions, character development, or an ending…Landis never seems very sure whether he's making a comedy or a horror film, so he winds up with genuinely funny moments acting as counterpoint to the gruesome undead. Combining horror and comedy is an old tradition (my favorite example is Bride of Frankenstein), but the laughs and the blood coexist very uneasily in this film.” I agree with Ebert wholeheartedly, but, from my perspective, the film’s unease cements its singularity. An American Werewolf in London coalesces toward a curiously empty conclusion, one punctuated by music that seems to suggest the film as an intelligent pastiche of its genre.

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video (premium subscription), Hulu (subscription)

Before Sunrise (1995, dir. Richard Linklater) — A meditation on time, Before Sunrise opens on a Eurail train from Budapest with two young people heading in divergent directions. While French Sorbonne student Céline (played by Julie Delpy) travels back home to Paris after visiting her grandmother, Texan tourist Jesse (played by a stupidly sexy Ethan Hawke) gets ready to wind down his European travel in Vienna. After striking up a conversation with her on the train, Jesse convinces Céline to disembark with him in Vienna. She complies, kicking off what I would classify as the most engrossing hour and 45 minutes of nonstop conversation ever captured on film. They spend the night wandering the city before Jesse’s early morning flight back to the United States, progressing through a series of encounters made mesmerizing by the film’s clever script, as well as Hawke and Delpy’s electric chemistry.

Richard Linklater — yes, the filmmaker behind Hit Man (2023) lol — conceived of this screenplay after spending a similar evening with a woman named Amy Lehrhaupt in Philadelphia. Per Slate: “Linklater met Lehrhaupt in fall 1989, when he was visiting his sister in Philadelphia. He was 29 and had just finished shooting Slacker (1990), and was staying there for one night while passing through on the way home from New York. Lehrhaupt was several years younger, about 20. They met in a toy shop, and ended up spending the whole night together, ‘from midnight until six in the morning,’ ‘walking around, flirting, doing things you would never do now.’” Before parting ways, the pair exchanged information, but their relationship eventually died out due to the distance.

Her impression on Linklater, however, remained; their encounter sparked the inspiration for Before Sunrise, a screenplay he came to co-write with Kim Krizan. According to Slate, “On a recent episode of the podcast The Q&A with Jeff Goldsmith, he recalled mentioning the movie idea to Lehrhaupt that night: ‘Even as that experience was going on…I was like, ‘I’m gonna make a film about this.’ And she was like, ‘What ‘this’? What’re you talking about?’ And I was like, ‘Just this. This feeling. This thing that’s going on between us.’” When the film debuted, Linklater expected it to reach Lehrhaupt, but he never heard from her. Years later, he learned that Lehrhaupt “died in a motorcycle accident on May 9, 1994, before she reached her 25th birthday. Before Sunrise started filming a few weeks later.”

Before Sunrise captures youth and transience in equal measure. The entire film more or less consists of an ongoing conversation between Jesse and Céline, meandering through topics ranging from gender to purpose to religion. As Roger Ebert writes in his 1995 review: “What do they talk about? Nothing spectacular. Parents, death, former boyfriends and girlfriends, music, and the problem with reincarnation when there are more people alive now than in all previous times put together.” Their philosophical openness, to me, reflects a kind of curiosity about life, about the future, that tends to wane with age, that becomes shackled to, then buried by, reality and responsibility; it belongs to a moment that, inevitably, will calcify.

The temporality of their time together, of their early twenties, manifests most prominently in the film’s final sequence. Discussing Linklater’s interpretation of Vienna, Ebert writes: “The city…is presented as a series of meetings and not as a travelogue. They [Jesse and Céline] meet amateur actors, fortune tellers, street poets, friendly bartenders.” The emotional quality of the evening gets formed by interactions, between Jesse and Céline, between the pair and those people they encounter. As the film closes, Linklater shows the spots that shape Before Sunrise abandoned by Jesse and Céline, more or less emptied of their inhabitants, at daybreak. The most memorable shot, for me, shows an elderly woman crossing through a park where Jesse and Céline shared wine the prior night. An empty bottle and glasses litter her path, operating as indexical signifiers of their prior presence; the objects connote a kind of melancholic emptiness and serve as a reminder that all things good and bad, big and small, will pass.

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video ($3.79)

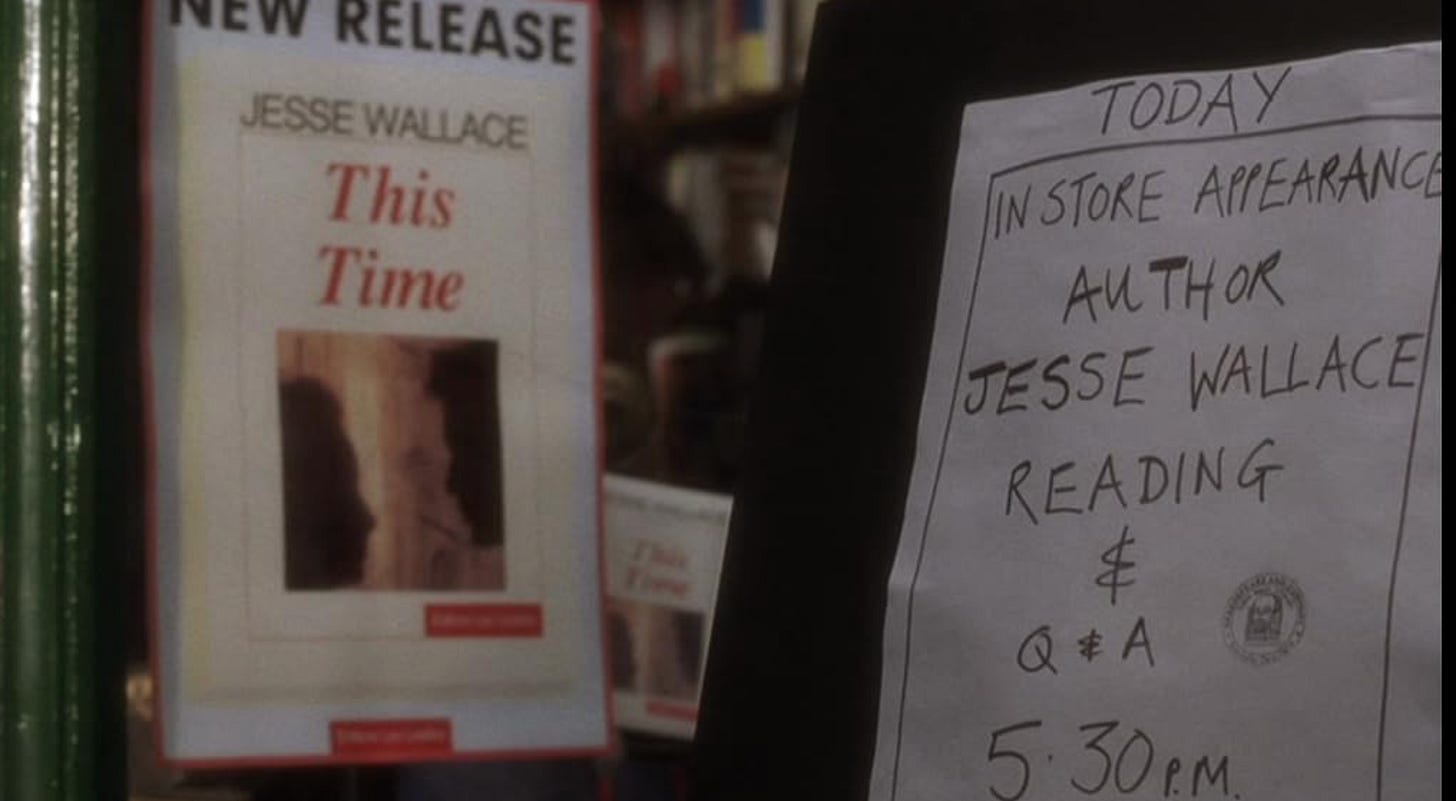

Before Sunset (2004, dir. Richard Linklater) — Before Sunset picks up where its predecessor left off — sort of. Jesse (played by a still stupidly sexy Ethan Hawke) reads the closing excerpt from his novel, This Time, a fictional retelling of the first film, at Shakespeare and Company in Paris. As he fields questions about whether the lovers meet again, Jesse notices Céline (played by Julie Delpy) watching his reading from the next room. The pair leaves the bookshop together and embarks on a walk around Paris, the kind of banter-laden stroll fans of the trilogy have come to expect. Linklater once again leverages long, uninterrupted takes to create a sense of verisimilitude, to simulate the illusion of an audience eavesdropping over the course of 80 minutes.

Released nine years after Before Sunrise (1995), Before Sunset carries markers of the passage of time — or, as my boy Roger Ebert puts it, “continues the conversation that began in Before Sunrise but at a riskier level.” Its actors have aged along with their characters, and their characters bear more baggage, the complications of death and marriage and children that remained in the first film’s future tense. Their conversations — adorned more prominently with despair — reflect this weight. Ebert continues: “They lead up to personal details very delicately; at the beginning they talk politely and in abstractions, edging around the topics we (and they) want answers to: Is either one married? Are they happy? Do they still feel that deep attraction? Were they intended to spend their lives together?”

Jesse’s flight back to the United States, scheduled for that evening, once again looms over their time together. I don’t want to say much else in the spirit of spoilers; as former Salon movie critic Stephanie Zacharek writes in her 2004 review: “To say too much about Before Sunset is to give the game away. Or, as Jesse himself says, ‘In the words of my grandfather, ‘To answer that would take the piss out of the whole thing.’’” But, I will quote a Letterboxd rando who says: “YOU CAN’T JUST END A MOVIE LIKE THAT NO NO NO NO WHAT I’M SCREAMING.”

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video ($2.99)

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962, dir. Robert Aldrich) — For one film and one film only, the two screen queens of 1930s Hollywood set aside their enmity (sort of) to bring audiences the bitchiest movie ever made. Joan Crawford and Bette Davis, whose legendary rivalry serves as the basis for Ryan Murphy’s first Feud season, star as sisters Blanche and “Baby Jane” Hudson in this creepy cult classic, a strategic collaboration designed to catapult its stars’ careers to new glory with age.

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? opens in 1917 with its titular character, a vaudeville child star (pictured above with her lookalike doll lol), on stage singing her signature song, “I’ve Written a Letter to Daddy.” Her older sister watches with their mother backstage, establishing the dynamic that defines the sisters’ relationship until its fateful reversal. As vaudeville falls out of fashion and “talkies” come to reign supreme, Blanche (played by Crawford) emerges as an acclaimed Hollywood star. She ensures her sister still secures roles by positioning them as a package deal, but Baby Jane (played by Davis) becomes a box office drag as she descends into alcoholism. In 1935, a mysterious accident occurs on a drunken Baby Jane’s watch, leaving Blanche paralyzed from the waist down. By 1962, the sisters live together in an old Hollywood mansion, paid for by Blanche’s film earnings. While Blanche maintains the financial upper hand, physical disability leaves her chained to the moods of her mercurial, sociopathic younger sister.

Iconic film critic Pauline Kael, queen of hot takes (see: her rave review of soapy, sexy Shampoo (1975), which moved the film toward the top of my to-watch list), famously slammed What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? for its plot, a narrative she deemed incoherent. In her 1964 essay for The Atlantic, “Are the Movies Going to Pieces?,” Kael writes: “Was it possible that audiences no longer cared if a film was so untidily put together that information crucial to the plot or characterizations was obscure or omitted altogether? What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? was such a mess that Time, after calling it ‘the year's scariest, funniest and most sophisticated thriller,’ got the plot garbled.” In other words, through this piece, Kael expresses concern over the notion that an audience could overlook a clunky plot in favor of a film’s vibes.

Does What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? have a winding, complex narrative that might leave viewers lost halfway through? Absolutely. Could it benefit from a shorter running time? Probably. But, the film maintains its merit for a few reasons. First and foremost, Davis and Crawford. As critic Luke Buckmaster aptly notes in his review for The Guardian, “Davis’s wall-rattling performance is…so strong, so toxically and overpoweringly good, it seems to swell and morph the very fabric of the production around her, lifting the whole film into a heightened state of melodrama…nothing is subtle, and nothing about Davis simmers. She cranks the dial to eleven, then snaps off the handle and feeds it to you for dinner – on a bed of your worst fears.” Meanwhile, Crawford serves as an empathetic foil, a container for the terror Davis elicits in the audience.

Second, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? refuses to conform to a formula and, in many ways, that “garbled” plot helps shape its uniqueness. A wild roller coaster of a ride, it discards the rules of horror, of cinema more broadly. The film’s bumpy narrative arc moves toward a lucid conclusion, even if the story twists, turns, and takes a couple detours along the way. Its ultimate clarity prevents it from the pitfalls that plague The Big Sleep (1946), for example, a resolutionless script sustained solely by the chemistry between real-life lovers Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall, from my perspective. (Per The LA Times: “Probably the best-known remark about the famously scrambled plot of The Big Sleep belongs to Raymond Chandler, author of the novel on which the 1946 movie was based. Asked who killed the Sternwoods’ chauffeur, a key murder left unsolved at the movie’s end, Chandler replied: ‘I don’t know.’”)

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? is fun. Bitchy without abandon, the script has so many killer lines with even better delivery (see: “But, you are, Blanche! You are in that chair!”) that will replay in your mind long after the film’s final credits.

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video ($3.19)

Stay tuned for the July Movie Review, which includes my thoughts on Before Midnight (2013), the final film in the Before trilogy!

xo,

Najet