A Look Back: June Book Review [2024]

For fans of “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination” (2018)

I fear I have adopted a Brideshead Revisited (1945) obsession as a new personality trait.

Also, some thoughts on Mary Gaitskill and Griffin Dunne.

Let’s get into it:

Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh (1945) — If 2018’s “Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination” holds the top slot for your favorite Met Gala theme, do I have a novel for you.

Set during World War II, Brideshead Revisited opens with Charles Ryder and his battalion sent to new headquarters at a country estate called Brideshead. The property propels Charles’s memory back to 1922, to his early days at Oxford, and chronicles his entanglement with the Flyte family, the home’s aristocratic owners, over the course of two decades. Rising sociopolitical tensions in Europe, the impending inevitability of World War II, creates a kind of pressure cooker for the narrative. The novel’s denouement dovetails with the final days before Hitler’s invasion of Poland, with what, in his preface from 1951, Evelyn Waugh characterizes as “a bleak period of present privation and threatening disaster.” Brideshead becomes a reflection of the Flyte family and the Flyte family the embodiment of England, a country haunted by shrinking stability by the summer of 1939 (“The weeks of illness wore on and the life of the house kept pace with the faltering strength of the sick man.”).

From my perspective, Brideshead Revisited operates, above all, as a novel about place. The country estate itself emerges as a site that bears witness to the changing tides of a family, of a country (“‘It doesn’t seem to make any sense — a family in a place of this size. What’s the use of it?’ ‘Well, I suppose Brigade are finding it useful.’ ‘But that’s not what it was built for, is it?’ ‘No,’ I said, ‘Not what it was built for.’”). Waugh reflects on the book as a work of nostalgia, a distillation of the mood that descended upon England during World War II. He writes in his preface: “It was impossible to foresee, in the spring of 1944, the present cult of the English country house. It seemed then that the ancestral seats which were our chief national artistic achievement were doomed to decay and spoliation like the monasteries in the sixteenth century…Much of this book is therefore a panegyric preached over an empty coffin…It is offered to a younger generation of readers as a souvenir of the Second War rather than of the twenties and thirties, with which it ostensibly deals.”

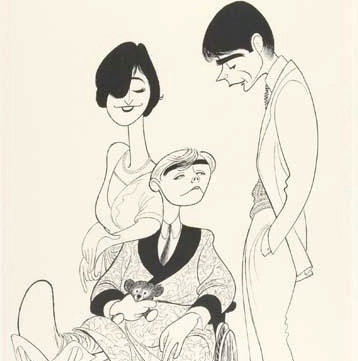

In a 2014 piece for The Guardian, book blogger Moira Redmond observes that Charles “falls in love not with a person, but with a whole family and their privileged way of life.” Over the course of the narrative, Charles’s fixation floats from Lord Sebastian (think Jacob Elordi’s Felix from Saltburn (2023) if he had alcoholic tendencies and carried a teddy bear named Aloysius everywhere) to Lady Julia (Sebastian’s sister and the tragic heroine of the novel, one whose moral dilemmas have spurred thinkpieces with titles like “The Julia Effect: Embracing Catholic Guilt”). But his connection to the Flyte family remains constant. Redmond goes on: “Even during the period when he doesn’t see any of the Flytes, Charles is still tied to them. His pictures of Marchmain House give him an entrée to society and lead to a career. He is shown as being unable to make a family of his own.”

Writing in first person, Waugh tools with notions of narrator reliability. Charles condenses prolonged conversations for brevity, each one mined from the murkiness of his memory (“She came to see me and, again, I must reduce to a few words a conversation which took us from Holywell to the Parks, through Mesopotamia, and over the ferry to North Oxford, where she was staying the night with a houseful of nuns who were in some way under her protection.”). The decorative splendor of a bygone era drips from each description. Waugh, reflecting on his prose from the vantage point of six years’ time, describes the novel as “infused with a kind of gluttony, for food and wine, for the splendors of the recent past, and for rhetorical and ornamental language.” He critiques the verbosity of certain passages, while also acknowledging the necessity of that “ornamental language” in establishing the novel’s mood.

Catholicism constructs its moral order. Back in March, I discussed Brandon Taylor’s Substack piece, “living shadows: aesthetics of moral worldbuilding,” which “urges contemporary authors to construct their fiction against more textured narrative reliefs.” Since then, Taylor’s piece frequently has served as a framework through which I meditate on film and fiction (see: my Killers of the Flower Moon (2023) review, last month’s discussion of Naomi Kanakia’s Dirt piece on money in modern literature, etc.). In it, he writes: “There is a tendency sometimes — more readily visible in the speculative and fantasy genres — to erect free-standing social and civilizational edifices without any real thought or care as to the chain of events or values that brought them about. I see this most often in the treatment of religion in contemporary fiction where no one prays, no one has any sort of deference for the spiritual life except as practiced by artists (usually writers), and where no one believes anything. It seems somewhat silly to say, but how can I as a reader care about people who do not have any beliefs? Who have no inner life except that which flashes temporarily upon the surface of whatever stray object has wandered into the direct path of the character?”

In Brideshead Revisited, Julia emerges as the antithesis of this contemporary dilemma, an example of how a character’s belief system can stoke tension in fiction. The entire Flyte family has a unique relationship to Catholicism. Lady Marchmain (Sebastian and Julia’s mother, the lady of the house), Brideshead (the eldest son, also referred to as Bridey lmao), and Cordelia (the youngest daughter) possess a pious sense of devotion, while Sebastian and Julia appear haunted by the moral order of their upbringing. Julia rejects religion on paper, but, in reality, it looms large in her conscience and becomes a core driver behind her decisions (“‘It may be a private bargain between me and God, that if I give up this one thing I want so much, however bad I am, he won’t quite despair of me in the end.’”). Charles, notably agnostic, repeatedly appears incredulous at the chokehold Catholicism maintains over the Flyte family. His liminal perspective, as I see it, helps ensure the novel’s sustained relevance by mirroring the contemporary confusion that Julia’s notions of love and religion as polarities might elicit.

“A panegyric preached over an empty coffin,” per Waugh himself, Brideshead Revisited captures an acute sense of anxiety. A sharp inhale in anticipation of unfulfilled cultural destruction, the novel distills perennial preoccupations around love, family, religion, home, and, above all, sense of place that span beyond “the period of soya beans and Basic English.”

The Devil’s Treasure: A Book of Stories and Dreams by Mary Gaitskill (2021) — A category-defying book, The Devil’s Treasure serves as equal parts short story, literary criticism, and anthology. In it, Mary Gaitskill aggregates snippets from her various novels and writings over the years — from Two Girls, Fat and Thin (1998) to Veronica (2005) to The Mare (2015) — and analyzes her influences with the gift of hindsight. She simultaneously pens a new short story about a little girl in search of treasure that dovetails with her chosen cuts.

First and foremost, if you haven’t read Gaitskill, I would not recommend this book as an initial introduction. From my perspective, it requires a baseline understanding of the types of stories she tells, “her central talent of extreme truth-telling about the human psyche and her willingness to go to awful places in search of it,” as The Paris Review food columnist Valerie Stivers writes in the McNally Editions blog. At the same time, I wouldn’t propose approaching it with the full scope of Gaitskill’s writing under your belt, as you’ll find yourself subjected to long re-reads of familiar passages. I would suggest starting somewhere in between, by reading her breakout series of short stories, Bad Behavior (1988), which I recommended in the June newsletter, for two reasons. First, the collection, as I see it, represents Gaitskill’s best work. Second, no excerpts from it appear in The Devil’s Treasure.

With that context in mind, this book emerged as a mixed bag for me. As someone with an avid interest in the process of fiction writing, Gaitskill’s early reflections on her work, on her emotional influences, compelled me. She teases out how her real experiences have translated to fictional planes over the years, coalescing to create the overarching mood of her prose. For instance, in The Devil’s Treasure, Gaitskill reveals that one of her father’s friends sexually assaulted her at age five. Stivers goes on: “Recalling this formative trauma, she says she was ‘mesmerized’ by what she saw happening in her molester’s face: a transformation from an ordinary person into ‘a creature consumed by hunger and shame and pain that drove him to do what he did, to act itself out on my body, my mind, everything in me that might feel.’ The experience shaped Gaitskill’s work, in the sense that she became aware of the ‘chasm between the normal face and the other face,’ and understood that ‘in that chasm anything might happen.’”

Meanwhile, I found Gaitskill’s analyses more defensive than reflective toward the back half of the book. Stivers concurs, writing: “The excerpts from The Mare are less effective than the author’s other work. The Dominican girl’s sections don’t have the ring of unblinking truth we have come to expect. And Gaitskill’s guilty-white-woman self-examination isn’t surprising the way her best work is.” In discussing her 2015 novel, Gaitskill explains her choice to adopt the perspective of Velvet Vargas, that young Dominican girl. She writes: “I referred earlier to the awkwardness I felt was inevitable in writing the book, awkwardness in the form of cultural mistakes, wrong details, words, tone — as opposed to my deeper understanding of the story. In this scene, those oppositions met, the knowing that I couldn’t get everything right, yet feeling the need and the will to create a world where mother and daughter could drop their ‘weapons’ and love in spite of all the forces against them.”

In her seminal 2019 essay for The New York Review, “Fascinated to Presume: In Defense of Fiction,” Zadie Smith discusses the question of who has the right to tell others’ stories, writing: “Is this novel before me an attempt at compassion or an act of containment? Each reader will decide. This is the work of an individual consciousness and cannot be delegated to generalized arguments, not even the prepackaged mental container of ‘cultural appropriation.’” In The Devil’s Treasure, Gaitskill reveals that she based Velvet on a young woman whose emotional life she knew quite well. That said, she had limited optics into how this teenager interacted with her mother. Nonetheless, without interviews or research, Gaitskill writes from the perspective of Velvet’s mother, relying on feeling alone to sustain her work. As a result, I would classify The Mare’s narrative as what Smith calls “an act of containment,” “an attempt at compassion” gone wrong, sloppily spurred by her faulty assumption of “awkwardness” as “inevitable.” Gaitskill’s persistent defense of it, to me, weakens The Devil’s Treasure, dilutes the potent self-reflection that shapes its earlier passages.

The Friday Afternoon Club: A Family Memoir by Griffin Dunne (2024) — I adored this memoir. I approached it with a bit of bias because Griffin Dunne and his siblings grew up in the Los Angeles of my mother and her siblings, a place, a moment, I always find myself eager to visit through stories. Both my grandfather and Dunne’s father — legendary Vanity Fair crime writer Dominick Dunne — got their hair cut by Jay Sebring up until the Tate-LaBianca murders. My mom and Dominique Dunne attended Harvard-Westlake at the same time, back when it was The Westlake School. But where my family lived in Encino, occupied the realms of Ford dealerships and real estate, the Dunnes resided in the Flats of Beverly Hills, their lives dominated by the twin titan industries of journalism and entertainment that shaped 20th Century Los Angeles.

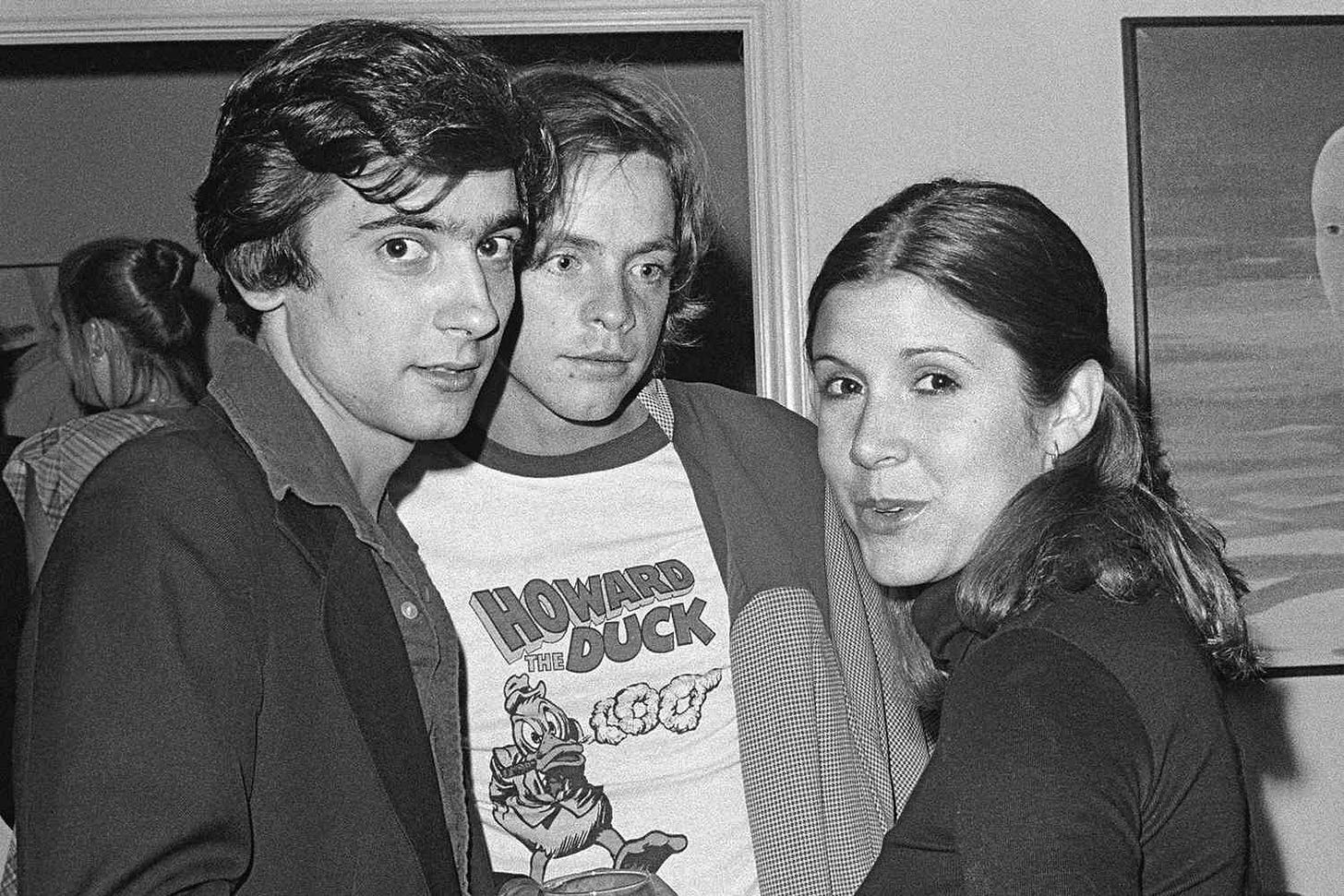

The Friday Afternoon Club is filled with wild anecdotes. Dunne lives a kind of Forrest Gumpian existence, with famous figures flitting in and out of some of his most formative moments. He recalls rolling his eyes when his best friend and roommate, Carrie Fisher, went off to England to shoot some sci-fi film, begging to stay at one of his Uncle John and Aunt Joan’s parties an hour later to hit on Janis Joplin. (My mom has similar stories of playing dress up in neighbor and fellow Armenian Cher’s closet as a little girl, of coming downstairs on a sleepy Saturday morning in 1973 to find Marcia Brady — aka: Maureen McCormick; unbeknownst to her, her brother’s new girlfriend — inexplicably making breakfast in the kitchen.) Per Vulture, Dunne “grew up in Beverly Hills at 714 Walden Drive, surrounded by movie stars. Sean Connery saved him from drowning in the family swimming pool. Jack Nicholson, Warren Beatty, and Roman Polanski all hit on his girlfriend at the same time (“Like three wolves sniffing a baby lamb,” he says). He…smoked pot with Harrison Ford when Ford was just his Aunt Joan’s carpenter.”

Each celebrity story serves a purpose, contextualizes the world that Dunne and his family inhabited. The memoir maintains a tone of self depreciation that, to me, makes it incredibly readable; in her review for The New York Times, Alexandra Jacobs rightly identifies that that Dunne “has a gingerly attitude toward fame, having witnessed its costs firsthand.” For instance, Dunne writes, after his breakout role in An American Werewolf in London (1981): “The truth was that I knew the attention that came with stardom would stir a self-awareness I was ill-equipped to handle, so committing to the next level of success paralyzed me with fear. My personal character was still undercooked, and my ego wasn’t strong enough to handle the scrutiny of fame, yet I was just wise enough to know that if I rushed headlong toward it, I’d soon burst into flames.”

In his acknowledgments, Dunne discusses his struggle to find a title for the book, while explaining that he always intended “A Family Memoir” to — rightly — serve as its subtitle. Per The Guardian: “Dunne is merely the latest in a long line of raconteurs and characters. There was the great-great-uncle who died in flagrante with his mistress on a yacht — his body was dressed in pyjamas and moved back to his hotel room on dry land, where his wife was told he had died in his sleep. There was the great-great-aunt who wed her lover just in time for them to attend her previous husband’s funeral as a married couple. But they are just the warm-up act for his immediate family: his father Dominick, his mother Ellen, or Lenny, and his siblings Alex and Dominique. The Friday Afternoon Club is named after the informal gatherings of actors Dominique would host each week.” The book captures the spirit of a family more than the story of a person, with Dominique — known for her bone dry sense of humor and penchant for bringing home scores of stray animals — at its emotional center.

While Part One of The Friday Afternoon Club recounts Dunne’s winding road toward his starring role in Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (1985), with the narrative threads of his family’s stories interwoven throughout it, Part Two centers on Dominique’s murder trial. Her killer, ex-boyfriend and Ma Maison sous chef John Sweeney, ultimately served only three years in prison for strangling her to death after the judge bungled the trial process, pushed the jury out of the room during key testimonials that proved Sweeney’s track record of violence against women. Dunne’s father — a closeted former film and TV executive who produced William Friedkin’s The Boys in the Band (1970), named his miniature poodles after Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas, and, to give you a full vibe check, recently had Nathan Lane tapped to play him in an upcoming Ryan Murphy series — experienced a fall from grace years earlier. After riding out his Hollywood banishment in the Oregon wilderness, he found a second career as a successful crime writer, first detailing the gross mishandling of his daughter’s trial, then famous cases from The Menendez Brothers to O.J. Simpson. The Friday Afternoon Club holds Dominique’s murder at its center, positions it as the dark mark that shapes the Dunne family for better and for worse in the years following her 1982 death.

In my review of Sloane Crosley’s new memoir, Grief Is for People (2024), I discuss how “Crosley decries authors who write ‘not ‘I miss this person,’ but ‘Miss this person as I do,’’ as ‘too much laundering of empathy.’” Dunne, like Crosley, avoids “laundering empathy” by breathing life into his now-deceased family, capturing the specific texture of their quirks. In The Friday Afternoon Club’s acknowledgments, he writes: “Alex is the only surviving member of my immediate family, but if it’s possible to acknowledge the dead, I want to thank my parents, Dominique, John, Joan, and Quintana for letting me bring them to life in my office each day as I wrote. Their presence was so vivid that the pictures of them on my corkboard actually shimmered with light. When my work on the book was complete, I mourned their losses all over again.”

Stay tuned for the June Movie Review, which will include thoughts on Griffin Dunne’s breakout role in An American Werewolf in London (1981)!

xo,

Najet