Happy first official month of summer!

Let’s get into it:

June Book Selections

The vibes are Juneteenth, Pride Month, and “Is Everyone on Vacation in Europe Without Me? (And Other Concerns).”

Recommendations for the month ahead include:

Bad Behavior by Mary Gaitskill (1988) — My friend Ama (hi, Ama!) is hosting another McNally Editions book club (more on that in a minute), this time centered on Mary Gaitskill’s The Devil’s Treasure (2021), “a bewitching collage of fiction, memoir, and mythography.”

Dip your toe into Gaitskill with Bad Behavior (1988), her debut short story collection. In a 2018 analysis of it for LitHub, Emily Temple writes: “I responded to Gaitskill’s stories instantly and intensely. I found them astonishing. I was seduced by the wildness of the characters, by their brazenness and force, even in the face of their own confusion, and often despite their inefficacy. I was interested and impressed, of course, by the amount and type of sex…But I was even more interested in the quality of mind with which Gaitskill imbued her characters. I had never read such chilly, sharp stories about women’s feelings. I had never read stories in which young women with what my mother might have called ‘questionable morals’ were taken quite so seriously.” +1 !!

Set primarily on the Lower East Side of the 1980s, Bad Behavior — riddled with “working-class drug addicts, intelligent hookers, stable housewives, smug yuppies, and sensually deprived professionals” — creates a mosaic of the era’s cultural landscape, “a cruel and tender world where romance and modern perversity go hand in hand,” per the back cover. Gaitskill laces passion with an undertone of violence, of sadism (“She immediately reminded him of a girl he had known years before, Sharon, a painfully serious girl with a pale, gentle face whom he had tormented on and off for two years before leaving his wife. Although it had gratified him enormously to leave her, he had missed hurting her for years.”). Her prose zooms in on the grotesque, underscores the beauty beneath the banal (“Her socks were thick and ugly, and her feet were large for her size. Details like this could repel him, but he felt tenderly toward the long, grubby, squeezed-together feet.”).

A Little Devil in America: In Praise of Black Performance by Hanif Abdurraqib (2021) — Taking its title from Josephine Baker’s speech at the 1963 March on Washington (“I was a devil in other countries, and I was a little devil in America too.”), this nonfiction essay collection from American poet, essayist, and cultural critic Hanif Abdurraqib traces a history of Black performance and its impact on the United States’s artistic landscape. Abdurraqib’s essays “brim with jubilation and pain, infused with the lyricism and rhythm of the musicians he loves,” examining moments ranging from Merry Clayton’s voice punctuating The Rolling Stones’s “Gimme Shelter” to Beyonce breaking the 2016 Super Bowl.

Discussing giants from Aretha Franklin to Whitney Houston to Sammy Davis Jr., Abdurraqib peppers his prose with moments of memoir (“I first learned to code-switch through the musical movements of my people, and done among my people in this way, it didn’t feel like a shameful burden. It felt like a generosity — a celebration of the many modes we could all fit into.”). Reviewing the book for the Ploughshares blog, writer and editor Julia Shiota observes: “His [Abdurraqib’s] approach to blending research and memoir imbues the lives of historical figures with a genuine warmth and care that is often missing from other approaches to reportage and history. No rigor is lost because of this love; in fact, Abdurraqib is even more incisive than critics who may have a bone to pick with the object of criticism. It’s through his love that he is able to reveal insights into the artists and performers themselves, as well as the way that history links to the present — both in his own life and in the wider world.”

Giovanni’s Room by James Baldwin (1956) — James Baldwin’s writings on and around Europe mark some of my favorites. No Name in the Street (1972), for example, draws chilling parallels between the Black experience in America and North African alienation in France through the lens of nonfiction. Giovanni’s Room (1956), one of Baldwin’s most famous works of fiction, follows David, an American man in Paris. Throughout the novel, David grapples with internalized homophobia, as well as his relationships with his girlfriend, Hella, and his former lover, Giovanni, an Italian bartender awaiting execution in a French jail cell (“Giovanni’s face swings before me like an unexpected lantern on a dark, dark night. His eyes — his eyes, they glow like a tiger’s eyes, they stare straight out, watching the approach of his latest enemy, the hair of his flesh stands up.”).

As always, Baldwin infuses his prose with a sense of visceral immediacy. Consider his repetition of certain words (“dark, dark night,” “his eyes — his eyes, they glow”), how the syntax of his narrator’s speech mimics the organic flow of thought. American writer and critic Hilton Als revisited the novel for The New York Times back in 2019. In his piece, Als reflects: “Baldwin asks, in Giovanni’s Room, what love looks like, ultimately, when we leave all those bags at the door — and if we can…like many morality tales, the story is meant to be instructive; the author wants you to love, but he doesn’t necessarily want the love he describes in his story to happen to you. And if it has happened to you, how to undo it?”

Tender is the Night by F. Scott Fitzgerald (1934) — F. Scott Fitzgerald walked so the ~euro summer~ girlies could run. Tender is the Night — Fitzgerald’s fourth, final, and most autobiographical novel — paints a portrait of a marriage undone by mental illness. The narrative teases out 17-year-old actress Rosemary Hoyt’s entanglement with Dick and Nicole Diver, a stylish American couple living on the French Riviera in the 1920s. Dick, a psychiatrist, descends into alcoholism while acting as doctor to his patient-turned-wife, Nicole (“Nicole is half a patient — she will possibly remain something of a patient all her life.”), and yearning for Rosemary (a stand-in for post-silent film starlet Lois Moran, with whom Fitzgerald had an affair).

Dick’s reliance on liquor mirrors Fitzgerald’s own alcoholism, while Nicole’s psychological suffering captures the infamous plight of Fitzgerald’s wife, Zelda. Back in 2017, Town & Country did a deep dive on the novel and its parallels to the Fitzgeralds IRL, noting: “Inside a copy of Tender is the Night that Fitzgerald gave to Zelda's psychiatrist, Robert S. Carroll, in 1936, the author wrote: ‘This book had a wide reading two years ago & was pronounced a critical success. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases...gave it a two page review…there is a good deal of my wife in it though of course I transposed everything factual in a world of fiction…the book…is true symbolically to the long tragic story of the last seven years.’ Fitzgerald then pointed out specific passages the doctor could peruse, presumably for insight into Zelda's condition — or at least her husband's view of it.”

Upcoming Content to Consume

Philharmonic in the Park (Dates: 6.11-6.14) — One of my favorite events of the year returns! Pack a picnic and head to your closest park — from Central Park to Prospect Park — for a free al fresco performance from The New York Philharmonic, a local tradition since 1965.

Per the site: “This summer, Thomas Wilkins conducts the Orchestra in a program that ranges from classics by Beethoven, Elgar, and Rimsky-Korsakov to Felix Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, with Randall Goosby as soloist, to new music by Carlos Simon and NY Phil Very Young Composers. All outdoor performances begin at 8:00 PM and conclude with fireworks!”

The Panic in Needle Park (1971) at The Paris Theater (Date: 6.13) — As part of its Bleak Week series, focused on “cinema of despair,” The Paris Theater will play Jerry Schatzberg’s The Panic in Needle Park (1971), aka: the inspiration for the Marnie and Charlie Girls episode.

Written by Joan Didion and her husband, John Gregory Dunne, the heroine-addled classic captures the culture of addiction that shaped 1970s New York through the lens of young lovers Bobby (played by Al Pacino in one of his first roles) and Helen (played by Kitty Winn). I saw this movie at Film Forum last year, and, while parts of it felt incredibly difficult to watch, I consider it a must-see as a result of its sustained cultural and aesthetic significance.

A highlight of my screening came in the form of a Q&A with director Jerry Schatzberg, which The Paris Theater will replicate. Schatzberg built his career as not only a filmmaker, but also an established photographer. He shot iconic images of Sharon Tate, Edie Sedgwick, Andy Warhol, Bob Dylan, and ex-girlfriend Faye Dunaway, among others, as well as street scenes around New York. In the Q&A I attended, Schatzberg showed some of his favorite stills, discussing the inextricable interplay between his photography and filmography.

Film Forum’s Out of the 80s Series (Closing Date: 6.13) — Film Forum’s four-week, 50-plus-film tribute to the 80s, which I wrote about last month, continues into June! Highlights to watch for ahead of closing include Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982), The Breakfast Club (1985), Back to the Future (1985), After Hours (1985), and Blue Velvet (1986).

I would especially recommend the 6.9 screening of After Hours, which includes a post-film conversation with star (and nephew of Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne) Griffin Dunne; I saw Dunne speak about the filming of this smaller Scorsese gem at The Paris Theater last year.

The Paris Theater’s Academy Museum Branch Selects Series (Closing Date: 6.16) — The Paris Theater’s partnership with The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles to co-present a selection of 18 films, one chosen by each branch of the Academy, closes this month, with films screening Wednesdays at 7:00 PM and Sundays at 12:00 PM.

As you’ll recall, this series opened back in April. This month’s selections including a handful of films on my to-watch list, including Ball of Fire (1941), In the Mood for Love (2000), and The Conformist (1970), as well as traditional and cult classics I have seen like Citizen Kane (1941) and Young Frankenstein (1974).

McNally Editions Book Club: The Devil’s Treasure (2021) by Mary Gaitskill (Date: 6.17) — My friend Ama (hi again, Ama!) runs a monthly book club at McNally Jackson in Downtown Brooklyn “centered around books that have been largely forgotten, the reissued classics and rare finds that have slipped from the mainstream and are waiting to be discovered by a new set of readers.”

For June, the pick is Mary Gaitskill’s The Devil’s Treasure (2021), “a bewitching collage of fiction, memoir, and mythography” that has Gaitskill, one of my favorite authors, reflecting on her creative process. Tickets are $5 and function as a voucher to put toward anything in the store!

Cinespia at Hollywood Forever Cemetery: What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) (Date: 6.29) — Cinespia screenings are back at Hollywood Forever Cemetery for the summer! I sent out a blast about Legally Blonde (2001), playing tonight, but my other pick for the month is What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962).

The classic horror flick focuses on aging child actress Jane Hudson (played by Bette Davis) and her wheelchair-bound sister, Blanche (played by Joan Crawford). Blanche plots to get even with her sister for the car crash that crippled her decades earlier, a pursuit at odds with Jane’s intent to map out a new rise to fame.

Miscellaneous Musings

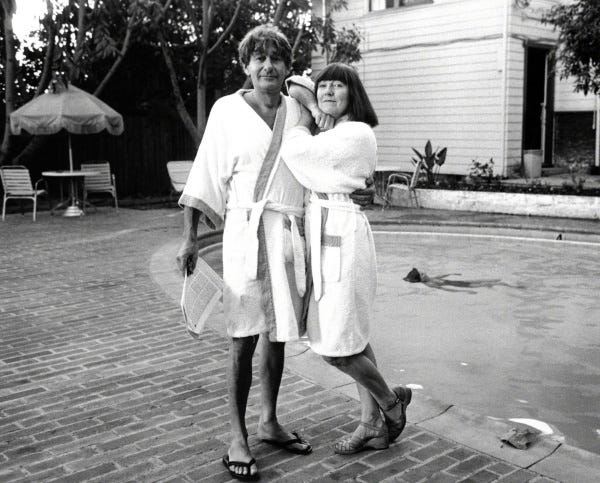

On Helmut and June Newton — Over Memorial Day, I had the pleasure of visiting The Helmut Newton Foundation in Berlin, where I saw the eponymous fashion photographer and “King of Kink’s” private collection. Per the site, “it includes films that shed light on the development of ‘Newtonian’ imagery, a collection of the photographer’s cameras, accessories, and other objects used in his photography…his numerous publications in magazines like Vogue, Elle, Vanity Fair, Paris Match, Stern, and Spiegel, as well as 100 posters of Helmut Newton exhibitions from 1975 to the present.” The crown jewel of this permanent exhibition, for me, came in the form of its focus on the relationship between Helmut and his wife, June. A photographer in her own right, June served as a partner and co-conspirator to her husband for decades, remaining dedicated to her craft and to him unto death.

Writer and actress Joan Juliet Buck developed a piece for Air Mail on the notion of June as “the mastermind behind the camera.” In it, Buck writes: “People speculated about his [Helmut’s] relationship with models, what his actual wife looked like, what she knew, what she didn’t know, and what there was to know. One of the sexiest photographs he ever took was of June lighting a cigarette at a dinner table, her dress pulled open to expose her breasts. Married for 56 years, citizens of the world, childless, they loved each other. June was not an amazon like his models, but a mastermind. Small, energetic, curious, always alert to nuance and depth, primed for approaching bullshit, June could see below the surface; her perspicacity could run acid, with a short list of short words to use on a long list of people.”

In June’s New York Times obituary, Penelope Green writes: “While Mr. Newton’s Berlin noir images were carefully constructed mise-en-scènes depicting sex work or bondage or some other dark fantasy — like the notorious photograph of the model and creative director Jenny Capitain posed in a German pension, naked save for a neck brace and a cast — Ms. Newton’s pictures were unmediated and intimate. Charlotte Rampling’s sharp eyes stare you down in a portrait from 1982; a young and beautiful Robert Mapplethorpe, shot in 1977, looks as if he would live forever; Graham Greene is quizzical and pensive in a photo from 1988.” In other words, Helmut and June understood the two sides that comprise the coin of intimacy.

Money in Modern Literature — YA novelist Naomi Kanakia wrote a piece for Dirt on the “conspicuous absence” of money from modern literature. In it, she reflects on the novel of the 19th Century, a form riddled with overt class stratifications, and makes the case for a return to financial clarity in today’s fiction (“In Jane Austen’s day, the size of a man’s income was a source of open discussion — this is no longer the case.”). She points to The Secret History (1992) as a novel that “at least attempts to discuss money” and Detransition, Baby (2021) as an “intricate comedy of manners…marred by the complete economic illegibility of one of its main characters: Ames works an upper-middle-class office job, but we’ve no idea if he has debt and can’t guess his salary to within even an order of magnitude.”

As I see it, this discourse runs parallel to Brandon Taylor’s Substack piece, “living shadows: aesthetics of moral worldbuilding.” As I discussed in March, Taylor “urges contemporary authors to construct their fiction against more textured narrative reliefs.” He views the development of distinctive moral landscapes as crucial antidotes to the novel’s current status as “dominated by Event and Situation, but without any orienting or organizing schemas to give it all any meaning.” Taylor references religious beliefs as having the power to infuse dimension; perspectives on money, as I view it, fulfill an analogous function.

Francis Ford Coppola Being Silly — If you’ve been here for the past few months, you know that one of the many things I love is Francis Ford Coppola Being Silly. Back in January, I wrote about Coppola biographer Sam Wasson’s appearance on The Bret Easton Ellis Podcast, during which he dove deep on the headache and a half that went into the making of Apocalypse Now (1979). The episode had so many gems, including a breakdown of Coppola’s single-minded dedication to making musical romance One From the Heart (1982) happen at all costs, pouring $23 million worth of budget into an absolute bomb.

In May, Wasson penned a piece for Air Mail that positions Coppola as “the last great dreamer in Hollywood” in tandem with the premiere of Megalopolis (2024) at the Cannes Film Festival. Coppola first conceived of the idea for Megalopolis in 1977 before beginning development in 1983. After multiple pauses and cancellations, he finally brought the sci-fi epic to life with a star-studded cast helmed by Adam Driver, but not without the melodrama that typically accompanies his production processes (Wikipedia rabbit hole here).

Wasson writes: “The early reviews are wildly divergent — perhaps thrillingly so. The Times of London called it ‘a head-wrecking abomination,’ while Deadline judged it ‘a true modern masterwork.’ But if you need a rallying cry, consider this, from Steven Soderbergh, who calls Megalopolis ‘one of the most sustained acts of pure imagination I’ve ever seen...Nobody has ever seen anything like it.’ Unless someone in Hollywood steps up, though, nobody — other than the lucky few who attended a friends-and-family screening in Los Angeles, and the attendees at Cannes, where it was shown earlier this week, and where it got a seven-minute ovation — ever will. Not on the big screen, where Coppola’s work belongs.”

Coppola, as always, illustrates the delusion that goes into actualizing the dream. Wasson goes on: “Whatever happens, ultimately, Coppola wins. Because long after this crop of interchangeable executives has come and gone, people will still be watching his movies — every one of them a passion project. ‘Many, many artists, writers, and philosophers were paupers all their lives, died thinking themselves failures,’ he says. ‘But, Sam, not me.’ Thank you, Francis, for keeping Utopia on the map.”

Supplemental Reading

As always, don’t forget to use archive.ph if you can’t access these pieces or any of the ones throughout my Substack!

The New York Times: OBITUARY: Helmut Newton, master of the perverse image

The Paris Review: Mary Gaitskill, The Art of Fiction No. 257

The Irish Times: Booze as muse: writers and alcohol, from Ernest Hemingway to Patricia Highsmith

The Paris Review: Bret Easton Ellis, The Art of Fiction No. 216

Air Mail: The Oral History of a Summer Classic: Four Weddings and a Funeral

Cocktail of the Month

In a nod to Tender is the Night (1934), written by F. Scott Fitzgerald, an avid gin drinker, as a June book pick, the cocktail of the month is…

This gin-based drink is a favorite of Isa and Gala, the main characters in Marlowe Granados’s Happy Hour (2020), which I recommended last month. Originated during World War I, the cocktail takes its name from the French 75-millimeter field gun, a mainstay of the French army at the time, per Difford’s Guide.

To make it, combine one and a half ounces of gin, ideally Hendrick’s, with three quarters of an ounce of fresh lemon juice and three quarters of an ounce of simple syrup in an iced cocktail shaker. Cover and shake the cocktail shaker vigorously until the outside feels cold.

Strain the mixture into a champagne flute and top with two ounces of champagne. Garnish with a long spiral lemon twist!

That’s all for now! If you know me IRL, you know I’ve had an especially hectic month, so apologies for being a bit behind here. Stay tuned for the April Book Review, May Book Review, and May Movie Review!

xo,

Najet