The vibe is Oscars season and also birthday month for yours truly.

Let’s get into it:

March Book Selections

A handful of the authors behind this month’s recommendations have one thing in common with me: March birthdays.

Here we go:

The Informers by Bret Easton Ellis (1994) — My problematic Pisces king published this collection of short stories, largely written during his time at Bennington College, in 1994. A shared web of characters stretches across the various vignettes, painting a precise portrait of 1980s Los Angeles.

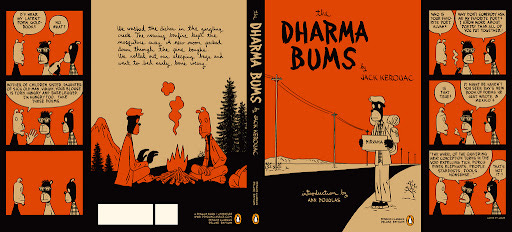

The Dharma Bums by Jack Kerouac (1958) — This novel, by my other problematic Pisces king, centers on Ray Smith and Japhy Ryder, aliases for Kerouac and Gary Snyder. (Kerouac’s work is famously extremely autobiographical, with names often serving as the only fictional element. He once said: “In my old age I intend to collect all my work and reinsert my pantheon of uniform names, leave the long shelf full of books there, and die happy.”)

As Nancy Wilson Ross put it in her 1958 review for The New York Times: “On the Road was a chronicle of the hitch-hikers, hipsters, jazz fans, jalopy owners, drug addicts, poets, and perverts of the Beat Generation. In the present book, however, not only are his [Kerouac’s] ‘bums’ considerably more respectable and articulate, but they are no longer merely moving for movement's sake…now in search of Dharma, or ‘Truth’ — are trying to learn to meditate in Buddhist style, their new goal nothing less than total self-enlightenment.” The novel follows Ray and Japhy as they seek transcendence in and beyond city life — until the former’s total retreat to Desolation Peak as a fire lookout for the summer.

Kerouac’s characteristically poetic prose culminates in a visceral view of nature (“In the morning I discovered a rattlesnake trail in the sand but that might have been from the summer before. There were very few bootmarks, and those were hunters’ boots. The sky was flawlessly blue in the morning, the sun hot, plenty of little dry wood to light a breakfast fire. I had cans of pork and beans in my spacious pack. I had a royal breakfast.”). Sharp insights splice his pastoral descriptions, coalescing in what Ross defines as “the not unrefreshing blend of naïveté and sophistication that seems to be this author's forte” (“Because in the end, you won't remember the time you spent working in the office or mowing your lawn. Climb that goddamn mountain.”).

Some might argue for On the Road (1957) as the ideal Kerouac introduction, and they’d probably be right, but The Dharma Bums marks my favorite of his work for that pursuit of purpose Ross identifies in her review.

The Virgin Suicides by Jeff Eugenides (1993) — The basis for the iconic 1999 Sofia Coppola film starring Kirsten Dunst, Eugenides’s debut novel frames the story of the Lisbon sisters’ suicides through the lens of a Greek chorus of teenage boys. He writes: “The Lisbon girls were thirteen (Cecilia), and fourteen (Lux), and fifteen (Bonnie), and sixteen (Mary), and seventeen (Therese). They were short, round-buttocked in denim, with roundish cheeks that recalled that same dorsal softness. Whenever we got a glimpse, their faces looked indecently revealed, as though we were used to seeing women in veils.” By carving out this collective narrative voice, Eugenides underscores the girls as local legends, as a microcosm of the spectatorship that surrounds girlhood.

In her 2018 introduction, Emma Cline — author of The Girls (2016), Daddy (2020), and The Guest (2023) — reflects on her experience re-reading her teenage copy of The Virgin Suicides, confronting her confusion around the highlighted passages that seem to have spoken to her on her first read. She draws a parallel to the boys’ experience in the novel, writing: “The past never leaves us, Eugenides seems to say, it just doubles and exposes, always shifting out of our grasp. The book is an elegy for how life passes through us…there is no memory that doesn’t fuzz around the edges.” The book blurs distinction between childhood and adulthood, reveals how the former refracts but refuses to fade.

Cinema Speculation by Quentin Tarantino (2023) — I will allow one (1) Aries. Tarantino’s new essay collection, which I‘ll discuss more deeply in the February Book Review, serves as a reflection on his personal experiences with 1970s cinema, an ode to the films that shaped his taste as a little boy growing up in Los Angeles. Conversational in nature, Tarantino’s prose creates the experience of sitting down with him over a couple of cocktails, getting his takes on well- and lesser-known films that formed the landscape of New Hollywood.

Valley of the Dolls by Jacqueline Susann (1966) — Okay, moving on from authors with March birthdays, nothing says Oscar season like a show business novel, and this pulpy, 1960s bestseller is one of the most fun. The basis for the cult classic film adaptation starring Peyton Place’s Barbara Parkins, Patti Duke, and my personal style icon Sharon Tate, Valley of the Dolls follows Anne Welles, Neely O’Hara, and Jennifer North as they strive to build careers in the entertainment industry.

The book and film fall into the category of my taste best defined as: “We’re having FUN we’re being SILLY does this look like a hard-hitting HBO drama to you people.” As Washington Post book reviewer Sibbie O'Sullivan puts it: “Valley of the Dolls may be the most beloved bad movie of all time, a fitting adaptation of the 1966 Jacqueline Susann novel it’s based on…the movie — which follows the exploits of three pill-popping female show-business wannabes — was roundly dismissed by critics. Roger Ebert called it ‘a dirty soap opera’ that failed even to ‘raise itself to the level of sophisticated pornography.’ Nonetheless, the film was, like Susann’s novel, a commercial success and, to many, a classic.”

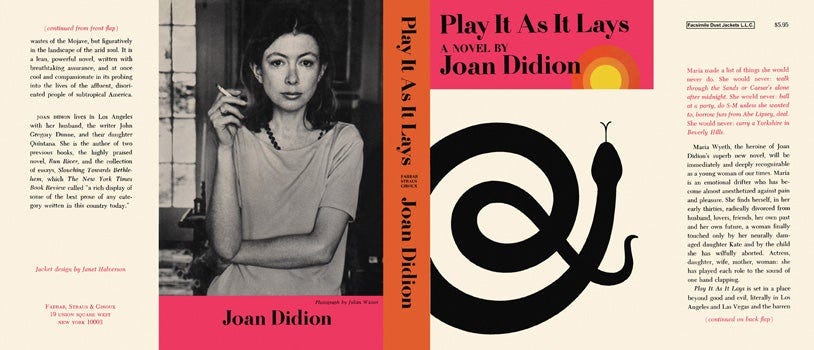

Play It As It Lays by Joan Didion (1970) — I revisited Didion’s second novel, a cornerstone in the canons of LA and Hollywood fiction, last month. Her sizzling prose shapes a series of three opening monologues told in first person, with the remainder of the book filling in the holes from the vantage point of a close third. Structurally, Didion collapses the linear framework of the traditional novel, replacing it with brief, sharp chapters that piece together the lead-up to fading actress Maria Wyeth’s institutionalization.

Play It As It Lays makes a strong pairing with Bret Easton Ellis’s Less Than Zero (1985), which I re-read back in December. In high school, Bret famously spent day after day poring over Didion’s prose, dissecting how her sentence structure embodies cool detachment. As a result, the two writers share thematic and formal similarities; for instance, consider the role of driving across both authors’ bodies of work or, more granularly, how they use commas to cultivate a sense of fluidity.

Upcoming Content to Consume

Metrograph: Girl, Interrupted (1999) (Dates: 3.1-3.2) — If you’ve followed this Substack from the beginning, you might recall that I reviewed Susanna Kaysen’s 1993 memoir in the first-ever monthly newsletter, writing: “In the opening pages of her memoir, Kaysen explains what it felt like to creep into madness, into a fabled Massachusetts mental institution, at age 18. She narrates: ‘It is easy to slip into a parallel universe. There are so many of them: worlds of the insane, the criminal, the crippled, the dying, perhaps the dead as well. These worlds exist alongside this world and resemble it, but are not in it…although it is invisible from this side, once you are in it you can easily see the world you came from. Every window on Alcatraz has a view of San Francisco.’ In the pages that follow, Kaysen weaves a beautifully crafted portrait of the 18 months she spent at McLean — the infamous psychiatric hospital that housed Sylvia Plath, James Taylor, Ray Charles, and, after Kaysen’s stay, David Foster Wallace — in 1967.”

I still have yet to see the 1999 film adaptation starring Winona Ryder and Angelina Jolie, and it’s coming to Metrograph this month as part of the theater’s Mad House or Mad World series. Per Metrograph, the 90s cult classic “sets its scene at a New England psychiatric hospital c. 1967 where Winona Ryder (in the Kaysen role) lands after suffering a nervous breakdown. Among the committed at Claymoore are a hall-of-fame lineup of ’90s female acting talent, including sociopathic agitator Jolie, self-harmer Brittany Murphy, and schizophrenic burn victim Elisabeth Moss. ‘A small, intense period piece with a hardheaded tough-love attitude.’ — The New York Times”

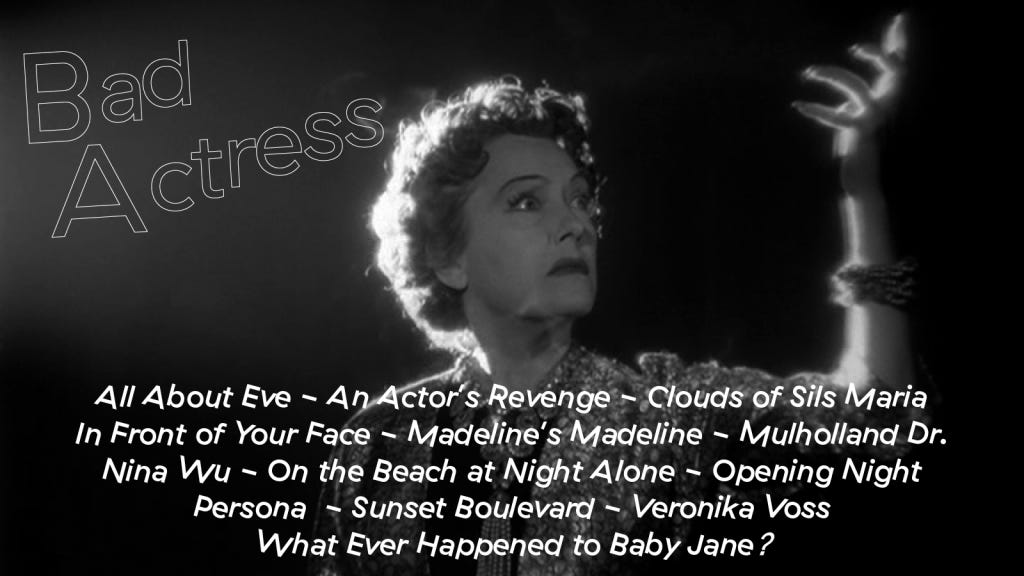

Metrograph’s Bad Actress Series (Dates: 3.1-3.24) — A series about mentally ill actresses, LFG !! As the site puts it: “To say an actress ‘loses herself in a role’ is usually applied as a compliment…but this series is comprised of movies where it might be used as an expression of concern. Bad Actress collects an all-star stock company of performers caught in the midst of mental breaks: sometimes chemically induced, as in R. W. Fassbinder’s Veronika Voss; sometimes driven by public abandonment, as in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard; and sometimes attributable to more mysterious causes, as in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive. After careers of performing for others, these actresses are acting out for themselves—and the result is the (often harrowing) performances of their lifetimes.”

I recommend checking out All About Eve (1950), Sunset Boulevard (1950), and David Lynch’s neo-noir masterpiece, Mulholland Drive (2001).

McNally Editions Book Club: Ex-Wife by Ursula Parrott (Date: 3.18) — I’ve praised this novel multiple times across newsletters, and my friend Ama — Beauty Editor at Coveteur and fellow fiction girlie who contributes to LARB — is hosting a discussion centered on it in at McNally Jackson in Downtown Brooklyn this month. Tickets are $5 and function as a voucher to put toward anything in the store!

New Beverly Cinema: Play It As It Lays (1972) and Puzzle of a Downfall Child (1970) Double Feature (Dates: 3.19-3.20) — For LA subscribers! For two nights only, The New Bev will screen the 1972 film adaptation of Play It As It Lays alongside Jerry Schatzberg’s Puzzle of a Downfall Child (1970).

Tuesday Weld stars alongside Anthony Perkins in Play It As It Lays, a film on my to-watch list for March on the heels of my recent re-read. While the film received mixed reviews upon its release, Weld and Perkins garnered critical acclaim for their performances, leading to Weld’s Golden Globe nomination for Best Motion Picture Actress in a Drama.

Puzzle of a Downfall Child stars Faye Dunaway as a former fashion model who, like Didion’s Maria Wyeth, recounts the details of her downward spiral. I have yet to see this film, but did have the pleasure of listening to Schatzberg speak following a screening of The Panic in Needle Park (1971) at Film Forum last year. I found myself struck by the depth of his aesthetic sensibilities, registering Jerry Schatzberg the photographer and Jerry Schatzberg the director as a singular entity for the first time. (Throughout his robust career, Schatzberg not only captured iconic fashion and cityscape shots, but also photographed the likes of Sharon Tate, Edie Sedgwick, Andy Warhol, Bob Dylan, and ex-girlfriend Dunaway, among others.)

The Paris Theater’s Milestone Movies: The Anniversary Collection - 1974 Series (Dates: 3.22-3.28) — This month, The Paris Theater is showing “fifteen of 1974’s best films…in honor of their 50th anniversary.” The line-up includes personal favorites Badlands (1973) and Chinatown (1974), as well as movies on my to-watch list like Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (1974), The Conversation (1974) and A Woman Under the Influence (1974), with nine of the 15 films screening in 35mm.

Syndicated BK: 2024 Oscar Nominated Shorts (Timing: Ongoing in March) — If you’re anything like me, you spend the Shorts sections of the Oscars every year wishing you had heard of more than one. This year, Syndicated is screening the full line-up in the weeks leading up to the Oscars! So are IFC and BAM, but you can’t order a cocktail to your seat at IFC or BAM, so…

Miscellaneous Musings

Brandon Taylor on Moral Worldbuilding — If there’s one thing I love, it’s a craft essay from Brandon Taylor, the author behind Real Life (2020), Filthy Animals (2021), and The Late Americans (2023). Taylor gave a Creative Writing Lecture at Columbia last week that I almost attended before ultimately deciding to Stay Home and Do Nothing. Luckily for me, he went on to publish it to his Substack, sweater weather.

The piece, entitled “living shadows: aesthetics of moral worldbuilding,” urges contemporary authors to construct their fiction against more textured narrative reliefs. He identifies an aesthetic shift away from internal thought and toward cinematic narration, a progression that, to me, seems to fulfill Alain Robbe-Grillet’s 1963 prophecy for the evolution of the novel. Taylor, famously a Henry James stan, characterizes contemporary fiction as “dominated by Event and Situation, but without any orienting or organizing schemas to give it all any meaning. All of which seems to be a commentary on how…non-meaningful life is out in the great concourse of mass subjectivity in which everyone is a protagonist and no one is a protagonist.”

With everyone and no one as protagonist, each individual becomes colored with the same palette. As Taylor puts it: “I would like to read fiction set in a world that has values and patterns of emphasis and de-emphasis. What matters in this word. It is not enough to undertake pure mimesis. Pure recreation of life in your art.” He calls for a two-fold solution to this dilemma for writers.

First, “ask better, deeper questions about the moral logic of the world you create and its value systems. Do not merely copy and paste the value systems of our world into your story. Ask yourself, is this particular milieu I am describing governed by the hazy rules I feel in my own life or by some set of more concrete if arbitrary norms. Think vividly and deeply about the governing logic of the values you give your characters. Indeed, give your characters values.”

Second, “return to an attitude of hierarchy with respect to our minor characters. Not narratively. But morally. We have to be willing to let some shadow of inarticulacy fall upon regions of our cast of characters.” Here, as I see it, Taylor calls for the reintroduction of villains — one-note villains without tortured childhoods or early twenties trauma — into fiction in the form of minor characters to offset the sympathetic wash painted over today’s protagonists.

“Sofia Coppola’s Path to Filming Gilded Adolesence” — You had to know you wouldn’t make it out of here without me discussing The New Yorker’s Sofia Coppola profile. This extensive piece by Staff Writer Rachel Syme dives deep into the filmmaker’s creative process and influences.

Coppola (like me lol) has a penchant for creating moodboards. Syme writes: “Coppola begins every film project by gathering visual inspiration. In her makeshift office on the soundstage, [for Priscilla] she had covered a large bulletin board with imagery including the Presleys’ wedding photographs, a glamour shot of Priscilla as a teen-ager, and several William Eggleston pictures of an empty Graceland. There is a famous Bruce Weber photo of Coppola’s stylishly bestrewn home office at the time of The Virgin Suicides, and this workspace bore some resemblance.”

Some of the most compelling aspects of the feature position Coppola in contrast to her father, shed light on the impact of her mother (who, as I discussed back in January, famously caught Francis cheating on her with two different women at once back in the 70s). Syme writes: “Francis’s best-known films took place in hypermasculine precincts—the Army, the Mob. [Sofia] Coppola was drawn to high-femme self-expression. At her parents’ dinner parties, she was always more interested in the ‘wives and girlfriends,’ she said. ‘They had the best Bakelite jewelry.’…Then she added, of her mom, ‘I’m sure seeing my first impression of womanhood as a woman who felt trapped, and her sadness, is related to the women in my films, more than to a side of myself.’”

Also, please note the fine print at the bottom of the piece: “An earlier version of this article misstated Jacob Elordi’s height.”

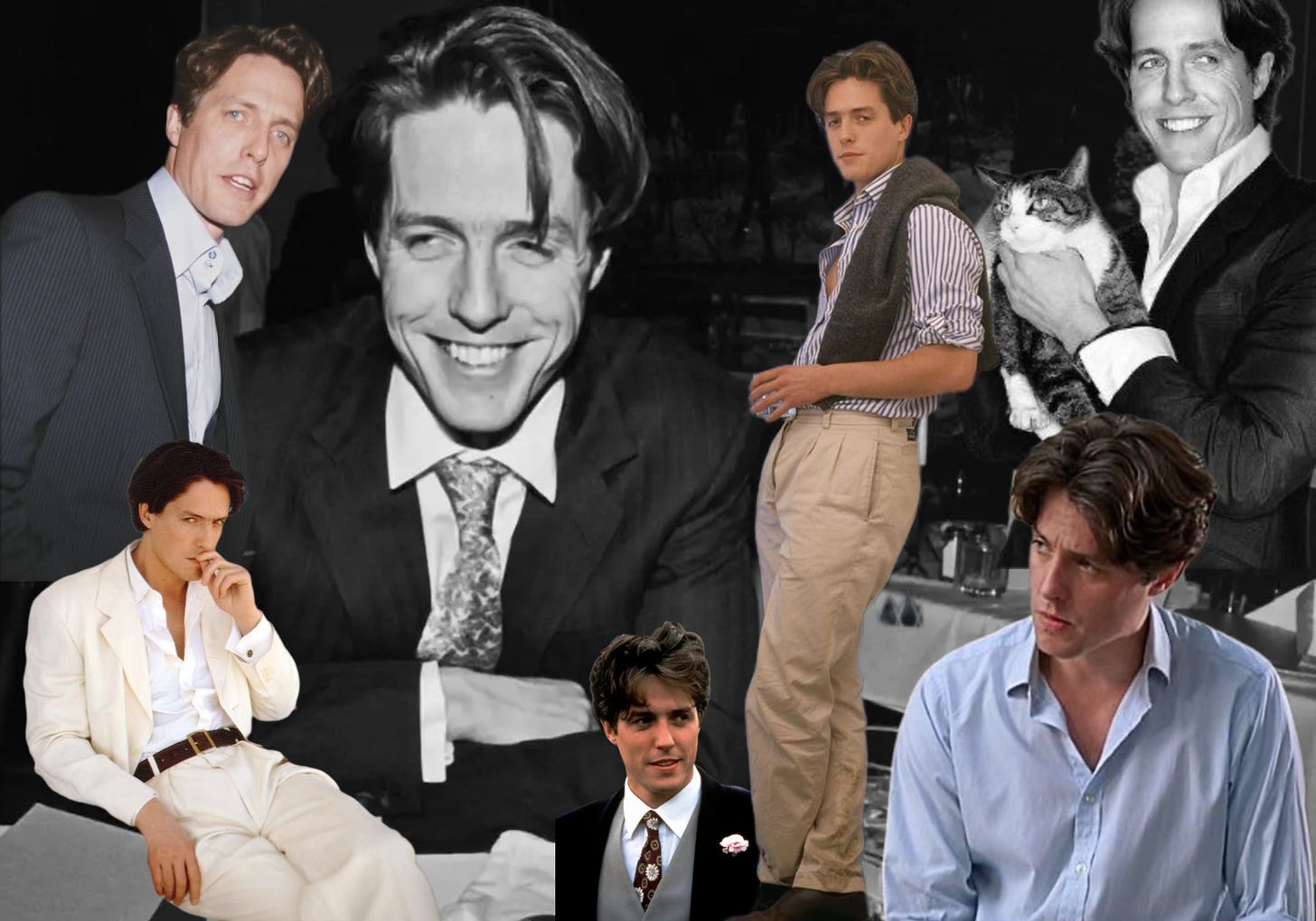

An Ode to Hugh Grant — One of my favorite authors wrote an ode to one of my favorite leading men. RT literally everything Marlowe Granados says, but especially:

“Delightful quotes from Hugh Grant that make me feel like me and him are more or less the same person:

On having children: ‘I think I’m just a bit of a glamour queen. I like the idea of flitting around the world, and not living in a semi-detached.’

On eventually (perhaps) becoming a writer: ‘That is still my fantasy. I should do that. Maybe as soon as these films are out… But I don’t know, I’ve probably wasted so much time now. But a couple of hours spent at the word processor makes me feel like a completely different girl…’”

Supplemental Reading

As always, don’t forget to use archive.ph if you can’t access these pieces or any of the ones throughout my Substack!

The Paris Review: Divorcée Fiction: On Ursula Parrott

ephemeras: Bridecore

Granta: A Good First Marriage is Luck

The Paris Review: A History of the Quaalude, Jordan Belfort's Drug of Choice

Interview Magazine: “We’re Not Crazy”: Emmeline Clein, in Conversation With Cat Marnell

Cocktail of the Month

The perfect cocktail for your Oscars party!

Gold Rush —

Pour two ounces of bourbon, along with three-quarter ounces of honey syrup and freshly squeezed lemon juice, into a cocktail shaker with ice. Shake until well-chilled, and strain into a rocks glass over one large ice cube. Garnish with a lemon twist.

That’s all for now! Stay tuned for the February Book Review and Movie Review in the coming days.

xo,

Najet