Happy Super Bowl Sunday!

Here’s the January Book Review in case you need a little content break during the big game tonight:

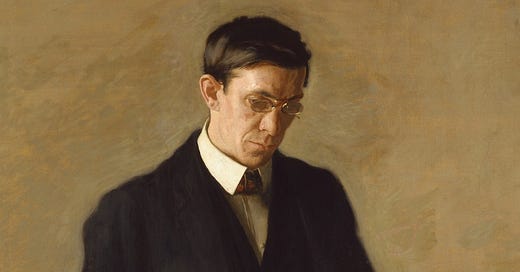

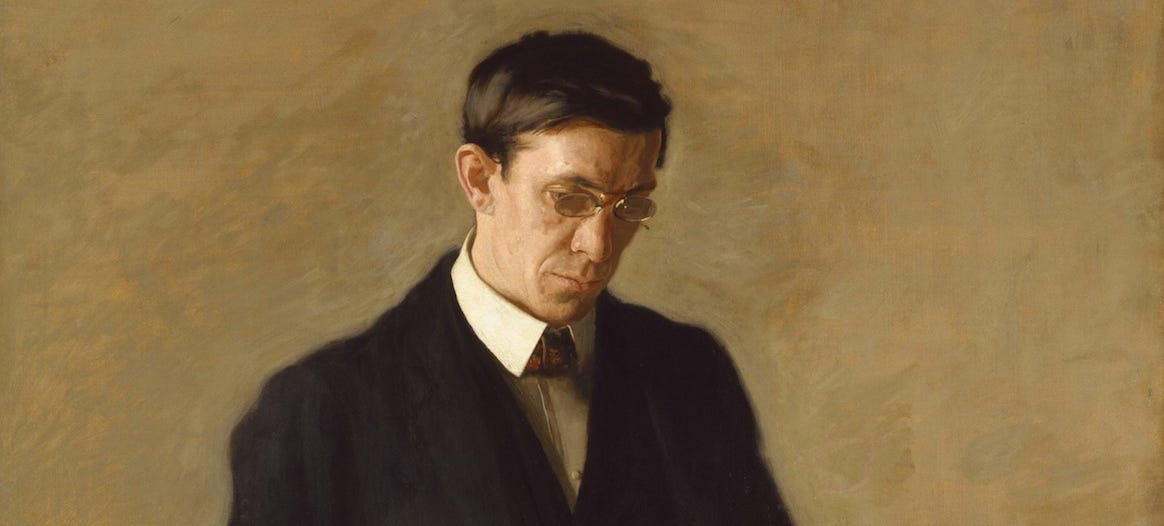

Stoner by John Williams (1965) — Bukowski once said: “An intellectual says a simple thing in a hard way. An artist says a hard thing in a simple way.” I adore this novel for Williams’s ability to write as an artist, to distill the full scope of a life with tender immediacy.

As I put it in the February newsletter: “This underrated classic — lauded by The New Yorker in 2013 as ‘the greatest novel you’ve never heard of’ — traces the life of University of Missouri English professor William Stoner. The opening paragraph gives a brief overview of Stoner’s career, noting that, ‘when he died his colleagues made a memorial contribution of a medieval manuscript to the University library…An occasional student who comes upon the name may wonder idly who William Stoner was, but he seldom pursues his curiosity beyond a casual question.’ With the framework of Stoner’s life and death established, the ensuing 270 pages fill in the specifics with a finer brush.”

Williams crafts an empathetic portrait of a path shaped by inaction. Stoner sticks to the status quo out of contentment, a perpetual choice that slowly shackles him. Early on in the novel, Stoner declines the opportunity to become English Department Chair; he feels comfortable in his current position, expressing no interest in taking on additional responsibilities. When his nemesis, Lomax, steps into the role instead, Stoner’s seemingly minute choice puts him in a position of subordinance for decades to come, limiting his professional and personal possibilities.

The emotional life of the novel reaches a fever pitch in its moments centered on the relationship between Stoner and grad student Katherine Driscoll. As I noted in the February newsletter: “It captures a rare merging of mind and body, what happens when attraction manifests both intellectually and physically. Engaging as equals, Stoner and Katherine ‘make love, and lie quietly for a while, and return to their studies, as if their love and learning were one process.’”

The Guardian aptly describes the prose as “clean and quiet; and the tone a little wry.” Narrating Stoner’s wedding, Williams writes: “Edith was walking down the stairs. In her white dress she was like a cold light coming into the room. Stoner started involuntarily toward her and felt Finch’s hand on his arm, restraining him. Edith was pale, but she gave him a small smile. Then she was beside him, and they were walking together.” Williams uses crisp, simple language, the welcome antithesis of the kind of overwritten MFA novel you might expect from a book focused on the trials and tribulations of a professor. The visual of Edith as “a cold light coming into the room” punctures the paragraph with a sense of foreboding, instills the promise of forthcoming doom.

A Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan (2011) — Back in 2011, Jennifer Egan, speaking with The Daily Beast, said: “I knew as far back as 2001 that I would write a book called A Visit From the Goon Squad, though I had no idea what kind of book it would be. As I worked on it, I kept wondering, ‘Who is the goon?’ I liked the sense that there were many answers. And then I found myself writing ‘Time is a goon,’ and realized that of course that’s true—time is the stealth goon, the one you ignore because you are so busy worrying about the goons right in front of you.”

Egan’s Pulitzer Prize-winning work serves as a meditation on time, on how past, present, and future perpetually interlock. It essentially operates as a collection of interwoven short stories despite getting billed as as novel — likely for sales purposes — and follows a cast of characters connected by rocker-turned-producer Bennie Salazar. The various vignettes occur across a span of over 40 years. Egan occasionally implements a telescopic lens to showcase the present’s impact on the future, contextualizing its importance.

All in all, this book was a mixed bag for me. I love formally inventive fiction, and A Visit from the Goon Squad garnered major attention for its non-linear narrative and interlocking cast of characters when it first published. (If you don’t believe me, google “jennifer egan powerpoint slide goon squad.”) My favorite sections included “Safari,” which I first discussed back in the October newsletter, and “Found Objects,” which centers on Bennie’s kleptomaniac assistant, Sasha.

I admire Egan’s prose; she shows more than tells, while including clarity markers to subtly orient her reader. For instance, she writes: “Sasha and Alex left the hotel and stepped into desolate, windy Tribeca. She’d suggested the Lassimo out of habit; it was near Sow’s Ear Records, where she’d worked for twelve years as Bennie Salazar’s assistant. But she hated the neighborhood at night without the World Trade Center, whose blazing freeways of light had always filled her with hope.” This passage grounds the reader in space and time through the lens of mood. Over the course of three perspective-driven sentences, we learn that Sasha and Alex are in Tribeca. We learn that Sasha worked as an assistant to Bennie Salazar for twelve years. We learn that we are in a post-9/11 landscape.

As a writer — one focused on infusing clarity into my own fiction at the moment — , I learned a great deal from reading A Visit from the Goon Squad. But I wouldn’t say I especially enjoyed it. From my point of view, Egan seems to break down the traditional structure of the novel for the sake of it rather than because the characters and their narrative require it. This approach results in an expertly woven tapestry that, despite moments of poignancy, comes across as emotionally hollow.

Tom Lake by Ann Patchett (2023) — I have such a riddled relationship with Ann Patchett’s body of work. I first came across her writing when Three Lives & Company selected her non-fiction essay collection, These Precious Days (2021), as one of my Books of the Month at the start of 2022. (I’ve talked about this before, but participants in the West Village bookstore’s program get one bespoke pick per month, chosen based on their taste rather than a one-size-fits-all for everyone on the roster.) I enjoyed it overall, and followed it up by reading the semi-autobiographical Commonwealth (2016), which I similarly enjoyed.

A year later, in the beginning of 2023, my book club chose Bel Canto (2001) as its next pick, and I couldn’t get over how bad I found Patchett’s fourth novel. The prose struck me as overwritten, the plotline — a hostage crisis in an unnamed South American country filled with heavy-handed allusions to opera, one that begins at a high profile diplomat’s birthday party — melodramatic and largely unbelievable despite its basis in truth, its inspiration drawn from the late 90s Japanese embassy hostage crisis in Lima, Peru. (Patchett uses the word “lovely” to describe nearly everything and everyone in the novel, leading “omg someone plz teach Ann a new word” to become my most frequent margin note.) Given the decade and a half publication gap between Bel Canto and Commonwealth, I figured Patchett’s style simply evolved over time, growing into a more mature version of itself. Her newest novel, Tom Lake, however, has prompted me to reconsider.

Set in the summer of 2020, Tom Lake centers on a family in northern Michigan — Lara; her husband, Joe; and the couple’s three adult daughters, Emily, Maisie, and Nell. As the family passes time together at the height of lockdown, Emily, Maisie, and Nell urge their mother to tell the story of her former relationship with famous actor Peter Duke, a romance that emerged during a 1980s summer stock production of Our Town. Narrated by Lara in first-person, the novel vacillates between past and present.

Despite its compelling premise, Tom Lake, to me, wholly lacks emotional stakes. Lara gets pushed into sharing the summer of 1988’s specifics by her Greek chorus of daughters. At every turn, she expresses ambivalence toward her past relationship, complete contentment with the reality of her present life. As Katy Waldman put it in her review for The New Yorker: “The novel’s alchemical transformation of pain into peace feels, at times, overstated…As Tom Lake goes on, the determined positivity begins to feel slightly menacing, or at least constrictive. Is Lara really that happy?” Internal peace has undoubted value, but it rarely serves as compelling fodder for fiction unless presented as part of a perpetual circle rather than a linear endpoint.

Thornton Wilder’s Our Town serves as scaffolding for the novel’s narrative. Repeatedly playing the role of Emily marks Lara’s young life, and Patchett includes an homage to the Pulitzer Prize-winning play in her Author’s Note. Waldman continues: “Lara uses the text as a touchstone, channelling its mood of elegiac acceptance as she carefully detaches herself from her old wounds and triumphs.” As I see it, Patchett’s focus on an often-produced piece of work, a favorite with high school theatre departments nationwide, comes across as corny, the equivalent of using Sally Rooney’s Normal People as a lit comp in a query letter. The juxtaposition between the work at hand — in this case, Tom Lake — and its gargantuan, widely-known point of reference — Our Town — underscores an inevitable breach in quality, painting the lesser of the two works as a footnote incapable of standing on its own.

That’s all for now! See you at the end of the month.

xo,

Najet