We did it! We made it through January, which, while cozy, has nothing seasonal or fun to elevate the vibes, unless you count my cat’s birthday, but I digress.

Finally, February has arrived, and Valentine’s Day, which I‘ve long characterized as Halloween with a better color scheme, and the start of Pisces Szn™ are upon us.

Here we go:

February Book Selections

Okay, so the vibe is Valentine’s Day for all relationship statuses (but not in a Colleen Hoover or Emily Henry way) with a little Pisces Szn™ chaser.

Recommendations for the month ahead include:

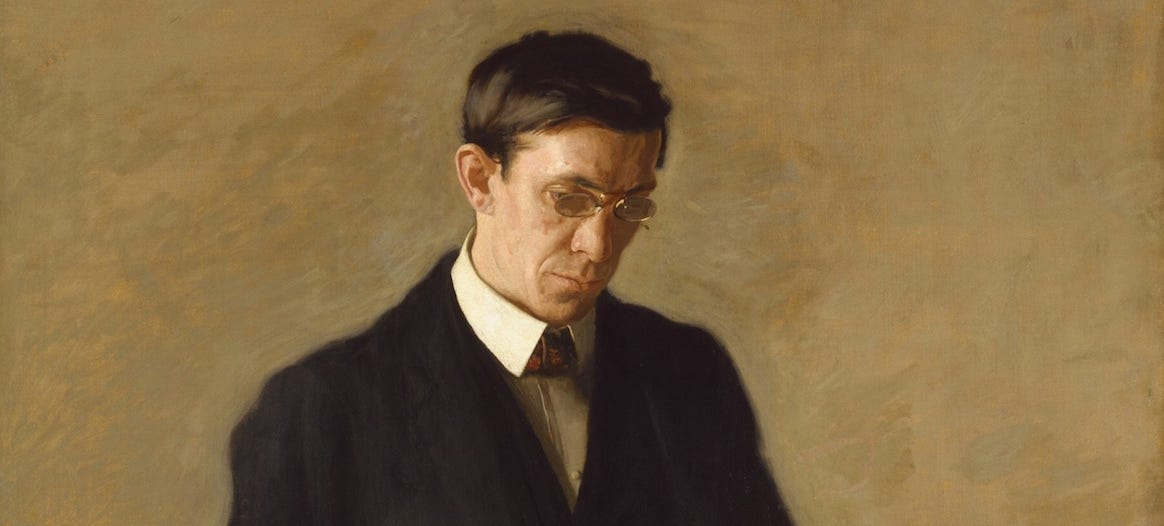

Stoner by John Williams (1965) — In the words of my friend Ama (hi, Ama), “gonna re-read the sections focusing on Katherine and Stoner’s love affair on Valentine’s Day for a reminder of what TRUE love is,” and I suggest you do the same.

This underrated classic — lauded by The New Yorker in 2013 as “the greatest novel you’ve never heard of” — traces the life of University of Missouri English professor William Stoner. The opening paragraph gives a brief overview of Stoner’s career, noting that, “when he died his colleagues made a memorial contribution of a medieval manuscript to the University library…An occasional student who comes upon the name may wonder idly who William Stoner was, but he seldom pursues his curiosity beyond a casual question.” With the framework of Stoner’s life and death established, the ensuing 270 pages fill in the specifics with a finer brush.

This novel does so many things well, which I’ll discuss in the January Book Review next week, but the relationship between Stoner and grad student Katherine Driscoll strikes a particularly poignant chord. It captures a rare merging of mind and body, what happens when attraction manifests both intellectually and physically. Engaging as equals, Stoner and Katherine “make love, and lie quietly for a while, and return to their studies, as if their love and learning were one process.”

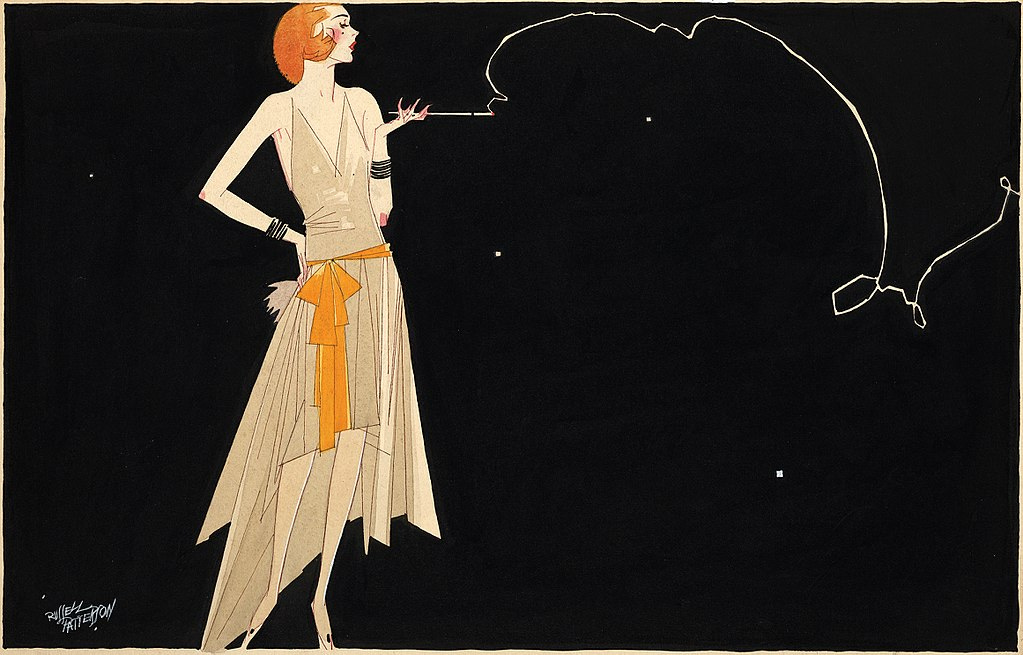

Ex-Wife by Ursula Parrott (1929) — For the single girlies! As discussed.

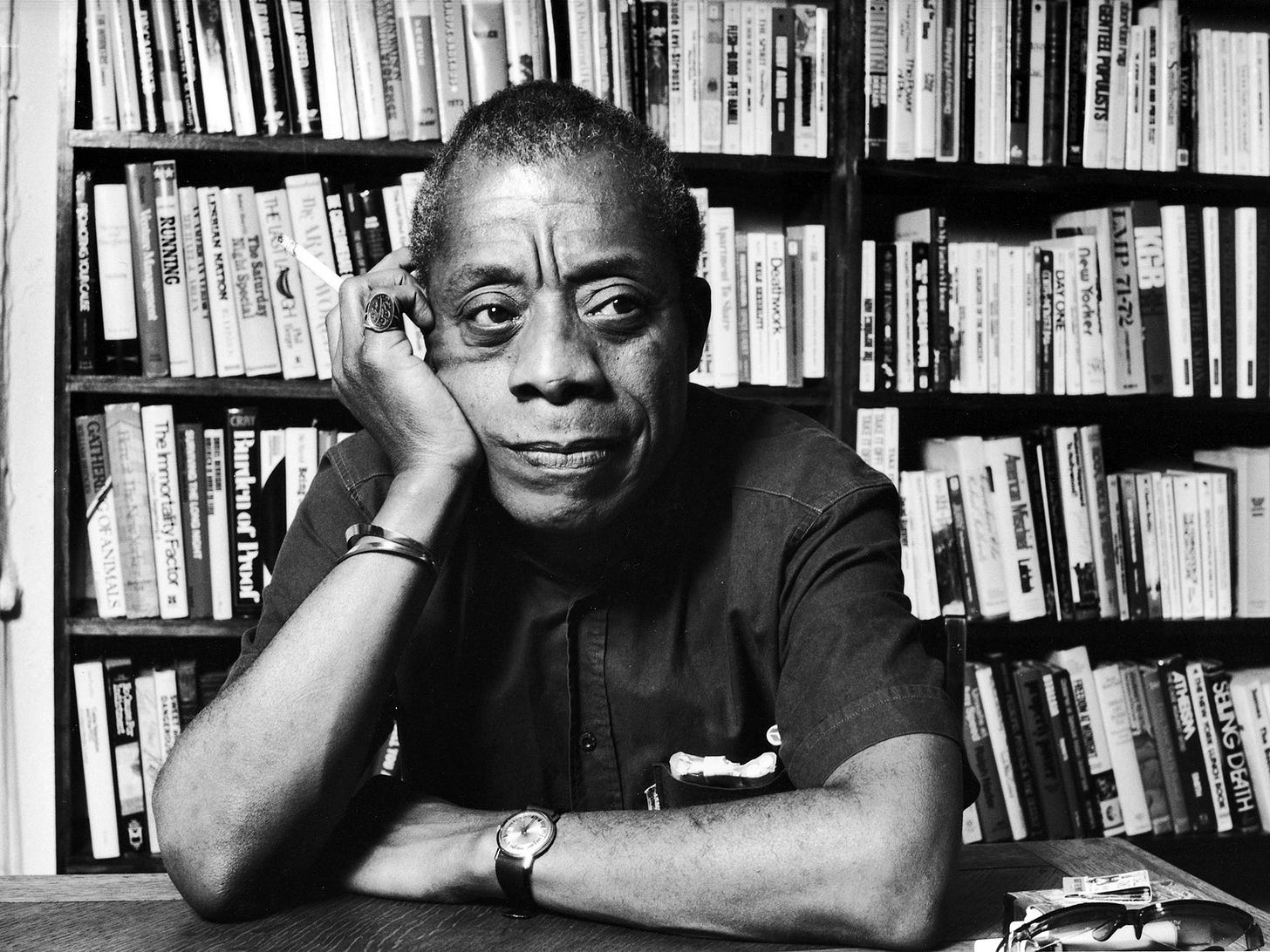

If Beale Street Could Talk by James Baldwin (1974) — The fifth novel from James Baldwin tells the story of Tish and Fonny, a young couple who grows up together and falls in love in Harlem. The thrust of the narrative tension centers on a false rape accusation thrust upon Fonny, lyrically exposing how systems of justice constantly fail Black people in the United States through the prism of a singular relationship.

Through Tish’s first-person perspective, Baldwin crafts a visceral sense of her and Fonny’s tender bond (“So I undressed and curled up on the bed. I turned the way I’d always turned toward Fonny, when we were in bed together. I crawled into his arms and he held me. And he was so present for me that, again I could not cry.”). The prose looks backward and forward simultaneously, building curiosity within the confines of relationship-driven fiction (“But on that particular Saturday night, we did not know; Fonny did not know, and we were happy, all of us.”). Harlem, the familial love that defines its community, shapes the book’s tone and becomes enlivened, in part, through the connection between Tish and Fonny’s families. Baldwin conveys the neighborhood’s sense of heritage and history, how its ties bind its residents decade after decade (“And everything seemed connected — the street sounds, and Ray’s voice and his piano and my Daddy’s hand and my sister’s silhouette and the sounds and the lights coming from the kitchen. It was as though we were a picture, trapped in time: this had been happening for hundreds of years, people sitting in a room, waiting for dinner, and listening to the blues.”).

This novel is, simply put, one of my favorite love stories. I haven’t seen the 2018 film adaptation, but, with Metrograph playing it this month, February feels like the perfect opportunity for a re-read and screening.

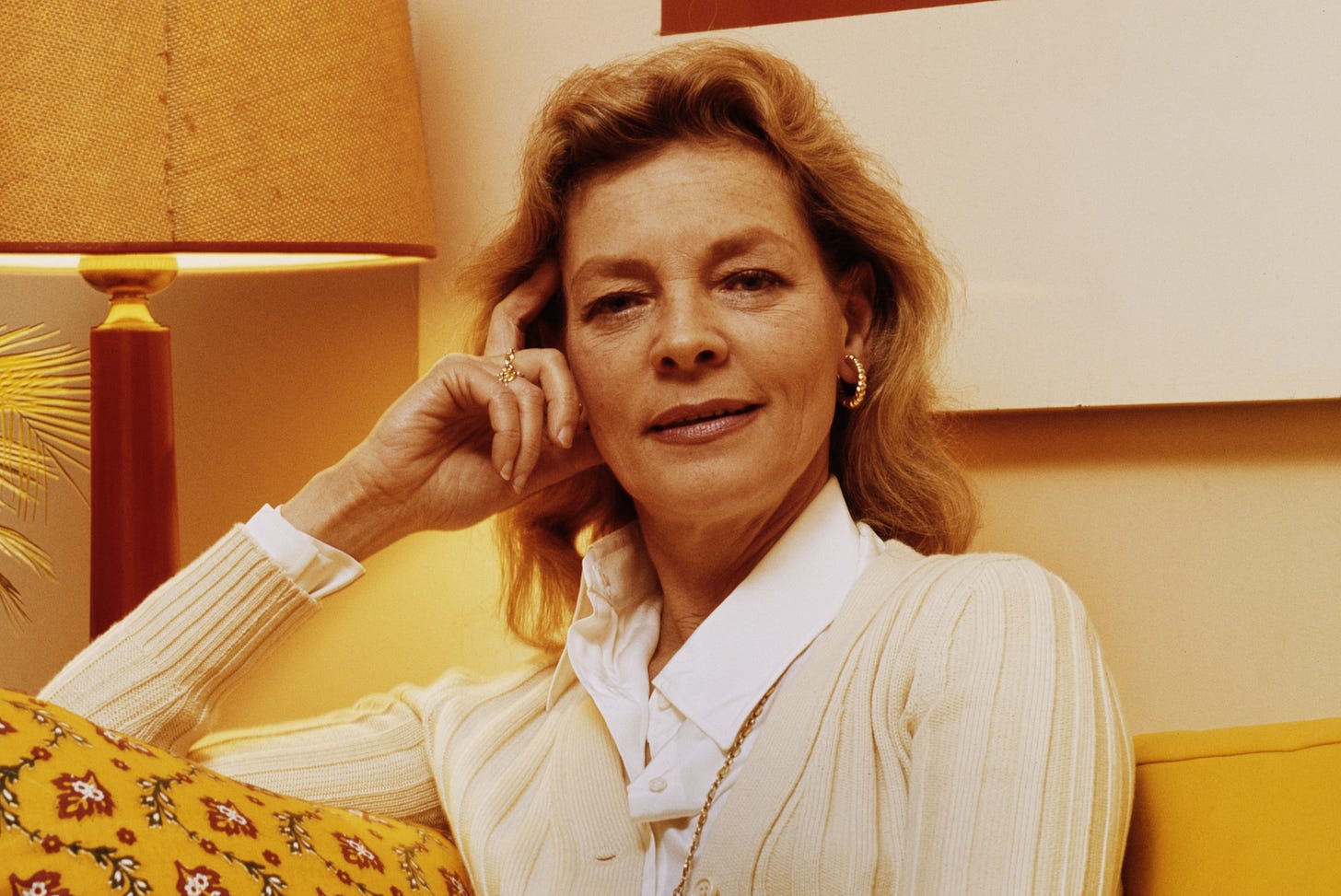

By Myself and Then Some by Lauren Bacall (2005) — This celebrity memoir — originally published in 1978 and updated with five additional pages in 2005 — was my Roman Empire back in 2017-2018. Written by Hollywood legend Lauren Bacall, By Myself and Then Some traces her career from her breakthrough role in To Have and Have Not (1944) to her Tony Award-winning performance as Margo Channing in Broadway’s Applause (1970).

Bacall became known for her candor and bone-dry humor, qualities that define By Myself and Then Some’s prose. Reading this autobiography feels like sitting down with its author for an hours-long series of drinks. In it, Bacall discusses her childhood in Manhattan, her teenage fixation with becoming the next Bette Davis, and how anxiety around antisemitism colored the early stages of her career. She reveals how a brief modeling stint ultimately gave way to her first-ever feature in the form of To Have and Have Not (1944) — and to her iconic romance with Humphrey Bogart.

Rather than exclusively focusing on Bacall’s early film career and the romantic relationship that came to define her life, the book encompasses her ill-fated engagement to Frank Sinatra, troubled marriage to Jason Robards, and successful second act as a stage actress. By Myself and Then Some weaves a complete portrait of a woman who **lived** and, as the title suggests, came to have immense comfort in her own skin.

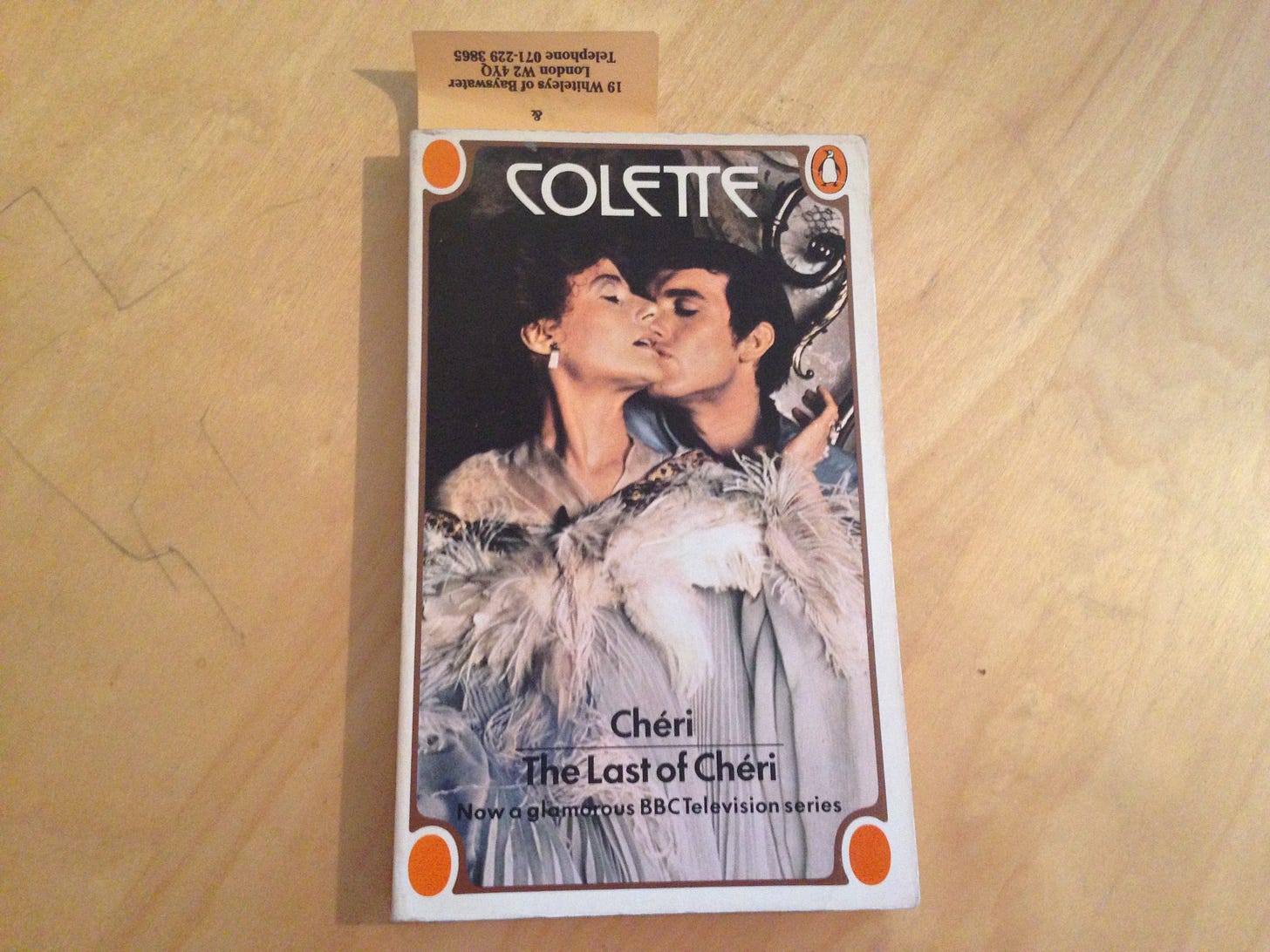

Chéri by Colette (1920) — Nothing says Valentine’s Day like French literature in translation, am I right? Chéri follows Léa de Lonval, a courtesan nearing fifty who has spent six years in relationship with the novel’s namesake, a playboy half her age. Chéri breaks the news that he plans to leave Léa and marry nineteen-year-old Edmée, cracking open the well of feeling bubbling beneath Chéri and Léa’s affair in what the back cover of my copy aptly characterizes as “one of the most honest, sensual, and poignant breakup stories ever written.”

In her 2001 introduction, Judith Thurman writes: “She [Léa] pretends — as much to herself as to her lover — that she’s relieved…to be getting rid of him. He is equally and uncharacteristically naive when he thinks he can exchange his aging mistress for a young wife with the same nonchalance he has replaced his stable of horses with a garage of motorcars. But their love affair (which Léa, in her moment of candor, refers to as an “adoption”) proves to be a much deeper attachment than those voluptuous, mercenary arrangements between erotically exigent older women and accommodating younger men that are so common in their circle.” Chéri functions as an exploration of denial and jealousy, of the often-gaping breach between love and marriage amidst the backdrop of a society mired in the specificity of its conventions.

I read and would highly recommend the Roger Senhouse translation, which includes Thurman’s 2001 introduction, quoted above, and The Last of Chéri, Colette’s 1926 follow-up to the original novel.

The Pisces by Melissa Broder (2018) — February 20th signals the start of Pisces Szn™, aka: the best astrological season of the year, in my extremely unbiased opinion (Leos, don’t come for me please; I’m sensitive). To mark the occasion, pick up a copy of Melissa Broder’s 2018 debut, The Pisces, my favorite of her fiction.

The Pisces operates as a meditation on depression, a pitch black comedy about love and listlessness. The mystical novel centers on Lucy, a grad student who has spent nine years trying — and failing — to write her thesis on Sappho’s body of work. “To to deal with her void,” as Jia Tolentino puts it in her review for The New Yorker, Lucy drives out to Venice Beach from Arizona to house- and dog-sit for her half-sister, becoming entranced with a young swimmer-who-turns-out-to-be-a-merman named Theo in the process.

I famously cannot get into fantasy fiction, but this novel stays somewhat grounded in reality despite its fantastical flares. Per Tolentino: “Lucy gets on Tinder, buys crystals, and chugs white wine. She is constantly asking half-baked rhetorical questions—“What was love without the spell?” “Did chasing the light inevitably lead us here?”—and generating yoga-class insights (‘You did not nurse from the breast itself but from a place beyond it’).”

Vogue describes The Pisces as “a little like one of those tweet-length flights of fancy spun out into book-length form,” a hit-or-miss genre for me depending on the author’s execution. From my perspective, Broder’s latest novel, Death Valley (2023), which I described as “quippy survivalist fiction, a magic-infused Eat, Pray, Love for 2015-era Twitter enthusiasts” back in October, falls more on the “miss” end of the spectrum. Meanwhile, The Pisces exemplifies what Vogue describes as Broder’s “talent for distilling graphic sexual thoughts, humor, female neuroses, and the rawest kind of emotion into a sort of delightfully nihilistic, anxiety-driven amuse-bouche.”

For me, the distinction between the emotional quality of the two novels stems from Broder’s handling of each narrator’s depression. In Death Valley, grief seems to come second to a kind of hollow comedy, operating as a means to a punchline. The Pisces, however, presents Lucy’s internal emptiness as scaffolding for the novel’s emotional and comedic cores alike.

Upcoming Content to Consume

Nitehawk’s Romance in the 1990s Series (Timing: Weekends in February) — Nitehawk has launched a series dedicated to celebrating the golden age of romcoms, with screenings happening at its Prospect Park and Williamsburg locations. The Prospect Park line-up will include Sense and Sensibility (1995), You’ve Got Mail (1998), Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994), and Notting Hill (1999). Meanwhile, Williamsburg will screen Clueless (1995), My Best Friend’s Wedding (1997), She’s All That (1999), and Muriel’s Wedding (1994).

All the movies play on weekends at 11:00 or 11:15 AM, meaning you can go and order brunch to your seat!

Metrograph’s Beach Bodied Series (Dates: 2.2-2.25) — It appears as though the programmers at Metrograph find this winter weather as violent as I do. As a remedy, the theater will roll out a “sampler of exemplary crime films where the capers are planned with the beach in easy reach, the getaways are run in flip-flops, and .38 holsters rest on top of Hawaiian print shirts.”

The line-up includes La Piscine (1969), a personal favorite, along with millennial classic Spring Breakers (2012). I’m personally hoping to catch Point Break (1991), Thunderball (1965), or Inherent Vice (2014), all of which I’ve yet to see.

Village East: Moonstruck (1987) (Date: 2.6) — This movie has everything. Cher. The Met Opera. Brooklyn Heights in the 80s. Italian food. Young Nic Cage in a wifebeater AND a tux.

Moonstruck tells the story of Loretta Castorini (played by Cher), a 37-year-old widow who, at the start of the film, seems to have found love at last despite her track record of bad luck. While caring for his dying mother in Sicily, Loretta’s fiancé, Johnny Cammareri (played by Danny Aiello), asks her to invite his estranged brother, Ronny (played by Nicolas Cage), to their wedding. Loretta goes to appeal to Ronny at his Brooklyn Heights bakery, and the lines between love and hate begin to blur.

Village East will offer three screenings of this classic on Monday (2.5)!

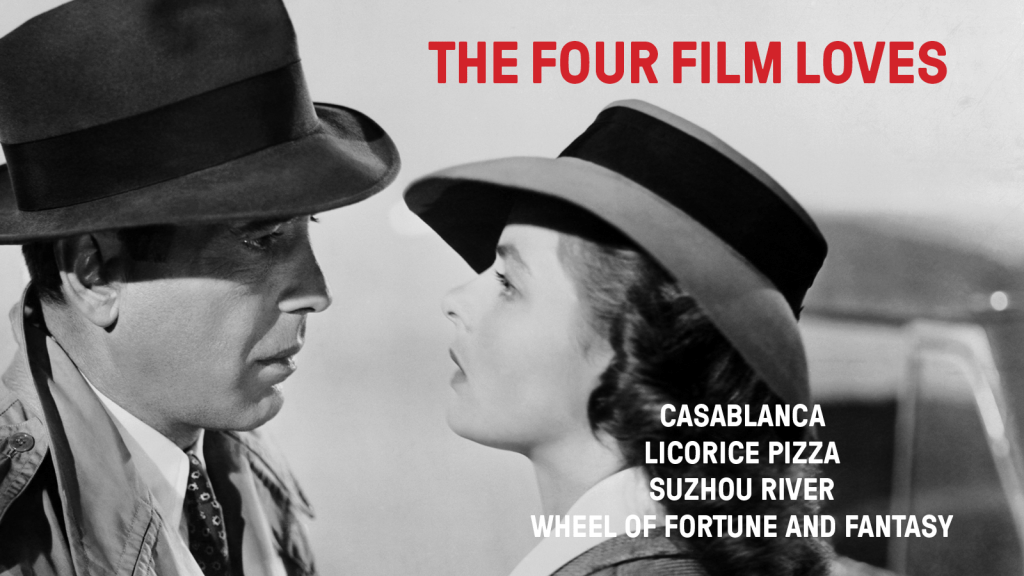

Metrograph’s The Four Film Loves Series (Date: 2.14) — Metrograph always has a banger of a Valentine’s Day line-up. This year, “The Four Loves, C.S. Lewis’s eloquent treatise on the nature of love, shapes and informs…[the] quartet of Valentine’s Day films at Metrograph. You can see one of cinema’s most famous star-crossed love affairs in Casablanca (representing Lewis’s concept of Philia, or the “friend bond”), the ’70s SoCal amour fou of Licorice Pizza (representing Lewis’s Eros, or “romantic love”), the triptych of sweetly ironic almost-love stories in Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy (Agape, or unconditional “God” love), and the noir-tinged study of sensual obsession of Suzhou River (Storge, or empathetic love).”

I talked about Casablanca (1942) — an arguably perfect movie — when IFC screened it last month. Despite its mixed reviews, Licorice Pizza (2021) remains one of my favorite films; it is Extremely Up My Alley, set against the backdrop of 1970s Encino with a Bowie-filled score.

Metrograph’s Baldwin, From Page to Screen Series (Dates: 2.14-2.24) — For anyone who missed Film Forum’s Baldwin series in January (from me @ me)! Metrograph’s homage to James Baldwin similarly will include James Baldwin Abroad (1971) and I Am Not Your Negro (2016), with the bonus addition of If Beale Street Could Talk (2018).

The Center for Fiction’s Art of the Short Story Series: Diane Oliver's Neighbors with Jamel Brinkley, Lan Samantha Chang, and Dawnie Walton (Date: 2.21) — The Center for Fiction’s Art of the Short Story Series, per the website, “explores the endless possibilities of storytelling in the short form” through conversations with veteran and debut authors alike. This month, the nonprofit will welcome a panel of Iowa Writers’ Workshop graduates to discuss the work of Diane Oliver.

An avid reader, Diane Oliver grew up in the Jim Crow South before attending University of North Carolina at Greensboro, where she served as editor of the school paper. Upon her graduation in 1964, Oliver earned a slot in the coveted Mademoiselle Guest Editor program, which, from 1938 through 1980, extended summer internships to an extremely selective group of college-age women. The likes of Joan Didion and Sylvia Plath participated, with Plath’s experience famously fueling The Bell Jar’s narrative. (As an aside: I highly recommend The Barbizon: The Hotel That Set Women Free by Pauline Bren if you’re interested in learning more about the program and its legacy; Mademoiselle had a partnership with The Barbizon to house its Guest Editors.)

Oliver’s work went on to appear in The Red Clay Reader, The Sewanee Review, and Negro Digest, facilitating her entry into the nearly all-white environment of Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the 1960s. In a piece for Bitter Southerner, cultural critic and writer Michael A. Gonzales positions Oliver as a narrative predecessor to Jordan Peele. He writes: “Oliver’s naturalistic prose feels as creepy as Shirley Jackson’s in her infamous tale of a small town and its annual rite in ‘The Lottery.’ While Jackson’s story was fiction — yet still upset many readers — the Jim Crow racism depicted in Oliver’s stories was real. Her style is packed with complex ideas told simply, but never as simply as ‘protest fiction.’ As a student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1965, her writing goals were literary, not preachy agitprop. The people she wrote about dealt with hundreds of years of real-life traumas that included slavery, lynchings, beatings, harassment, and constant uncertainty.”

Oliver died in a motorcycle accident in 1966 at the age of 22, just weeks before her Iowa graduation. Per Gonzales: “Both Jet and Negro Digest published obituaries. Jet said the young writer had accepted an editorial position to begin upon graduation. Negro Digest called Oliver’s death ‘a premature climax to a short, but notable career in which it was our pleasure to publish some of the budding writer’s work…Along with her writing, Miss Oliver was involved in many campus activities including Civil Rights and Vietnam protest demonstrations. Her last summer was spent as a teacher’s aide in Operation Head Start…We were saddened by her death, but we choose to remember the warmth of her smile.’”

Oliver’s first and only short story collection, Neighbors and Other Stories, published in July of 2022.

Miscellaneous Musings

“Mr. Salary” by Sally Rooney (2017) — If you’re looking for a short, steamy Valentine’s Day vibes read, this Sally Rooney story, one of her earlier efforts, is it. The piece centers on Sukie, a young woman returning home to Ireland from grad school in Boston to visit her sick father. Without spoiling too many specifics, her dynamic with Nathan, an older family friend and former roommate, drives the thrust of the tension in the piece.

F. Scott Fitzgerald frequently spoke about circling back to comparable characters, similar themes, throughout his work. He said: “Mostly, we authors must repeat ourselves — that’s the truth. We have two or three great and moving experiences in our lives — experiences so great and moving that it doesn’t seem at the time that anyone else has been so caught up and pounded and dazzled and astonished and beaten and broken and rescued and illuminated and rewarded and humbled in just that way ever before.”

Sally Rooney undoubtedly exemplifies this class of author. “Mr. Salary” shows her streamlined prose, her narrative preoccupations, in their incept — and, from my perspective, operates as a higher quality iteration than some of her later, longer form work (@ Beautiful World, Where Are You).

“Ahegao” by Tony Tulathimutte (2024) — This new short story from O. Henry Award winner and Private Citizens author Tony Tulathimutte closely follows Kant, a 30-something Thai American man grappling with his sexuality.

As the story opens, Kant comes out as gay to family and friends via a listserv-style email. Tulathimutte establishes a kind of false climax here, denouncing the notion of Kant announcing his queerness as a narrative apex by shifting focus toward his proclivity for BDSM. The breach between his sexual fantasies and experiences gapes as Kant embarks on his inaugural sexual explorations as a gay man (“They agree being in their late twenties/early thirties they are too old for clubs (though unlike Julian, Kant haas never been to one.)…And he’s put off by the novel dimension of smell — however filthy his fantasies are, they never have an odor, and Julian’s is eye-wateringly tart.”).

Tulathimutte crafts detail-rich prose that reflects broader emotional truths through the specific prism of Kant’s circumstances. For example, he writes: “Here, Kant perceives the true rift between them: Julian doesn’t know the difference between embarrassment and shame. How shame soaks, stains, leaves a skid mark on everything, and, when it has nothing to stick to, spreads until it does. Embarrassment is contained by incidents, gets funny and small over time; shame runs gangrene through the entire past, makes the future impossible.” This particular passage distills embarrassment and shame into a dichotomy with two distinctive poles that the reader can visualize, smell, feel. Vivid visual imagery — the notion of shame soaking, staining — renders a set of abstract concepts tangible.

This story is paywalled for subscribers to The Paris Review, and it doesn’t work on archive.ph, my usual go-to. If you don’t have a membership and want access, email me, and I can send you the PDF!

Only Murders in the Building — If you’ve been here a while, you know I don’t watch a ton of TV, simply because, if a show hits, I become so fixated on it that I turn into a loaf and accomplish nothing. (Ask me about the time I stayed up until 4:00 AM the night before my first day of eighth grade watching One Tree Hill on my portable DVD player.) When I do watch it though, my taste can be best summarized as “We’re having FUN we’re being SILLY does this look like a hard-hitting HBO drama to you people,” to quote the Riverdale subreddit.

To that point, I’ve been really enjoying Hulu’s Only Murders in the Building, which has my two favorite TV components: characters who feel like fictional friends and a solid murder mystery. Plus, this show has the added bonus of capturing the specific texture of the Upper West Side, from cranky co-op presidents wheeling utility carts to restaurants thematically predicated on pickles. For those of you unfamiliar, the Emmy-winning series stars Steve Martin, Martin Short, and Selena Gomez as Charles, Oliver, and Mabel, respectively, a trio of neighbors who start a true crime podcast centered on solving the murder of a fellow tenant.

Supplemental Reading

As always, don’t forget to use archive.ph if you can’t access these pieces or any of the ones throughout my Substack!

The New Yorker: Why Are Millennials Still Attached to American Girl?

The Paris Review: Addy Walker, American Girl

Vanity Fair: The Definitive Oral History of How Clueless Became an Iconic 90s Classic

Bitter Southerner: The Short Stories & Too-Short Life of Diane Oliver

Air Mail: Review Bombers: The Goodreads Problem

Cocktail of the Month

A sexier, smokier version of my personal favorite cocktail, the Paper Plane.

Naked and Famous —

Add one ounce each of freshly squeezed lime juice, Aperol, yellow Chartreuse, and mezcal (preferably Del Maguey Chichicapa) to a cocktail shaker filled with ice. Shake and strain into a coupe glass to serve.

That’s all for now! Stay tuned for the January Book Review next week.

xo,

Najet