The impending end of Riverdale — The CW’s long-running teen drama that has famously included plot lines peppered with everything from serial killers next door to Dungeons and Dragons knock-offs to organ harvesting cults led by Chad Michael Murray — has prompted me to consider my love of an ever-fading genre: the 22-episode-a-season teen drama. From Beverly Hills, 90210 (the original, not the 2009 reboot, although that’s cool too) to Dawson’s Creek to The OC to One Tree Hill to Gossip Girl (the original, not the 2021 reboot; that one’s not cool), this type of television has influenced my thinking and writing as much as, if not more than, my Holy Literary Trinity of Joan Didion, Bret Easton Ellis, and Eve Babitz. I can already hear the refrain of “Then, you’re probably an idiot and a shit writer,” which maybe, but hear me out.

Teen dramas always draw criticism, whether rightly (@ the Gossip Girl pilot’s casual depictions of attempted date rape) or wrongly (idk, I felt #seen by Dawson’s Creek’s so-called unrealistic dialogue in tenth grade), typically on a mass scale. Riverdale serves as a prime example; over the past seven years, thanks to @nocontextrvd’s noble work, I’m sure you’ve seen screencaps on Instagram and Twitter — sorry, “X (formerly Twitter)” — about Archie boxing a bear and the epic highs and lows of high school football without having watched an episode in years, if at all. The teen drama of the moment’s ubiquity forces a kind of low-level awareness across the pop cultural landscape, in many instances, inviting early-season defectors to serve as perpetual detractors, constant critics.

“The first season was so good, but, after that, it kind of jumped shark.” “They should have stopped after the high school years.” “That show’s STILL on the air?” These grievances tend to become frequent refrains — again, some rightly, some wrongly — and occasionally stem from writers and cast members themselves. The OC achieved widespread critical acclaim for its smash hit of a first season back in 2003, packing enough action into its initial run to fill four seasons of its predecessors, “burn[ing] bright, but fast,” as showrunner Josh Schwartz admitted in a recent Vanity Fair interview. Speaking to Wonderland about Dawson’s Creek in 2008, Michelle Williams said: “Don’t get me wrong, it was great in the beginning and I was grateful but towards the end the quality started to diminish.” Riverdale recently went so far as to insert a hyper-meta exchange into one of its recent episodes, in which Lili Reinhart’s Betty says: “We’re big fans of your program.” Madelaine Petsch’s Cheryl then adds: “Especially the first season. It kind of went downhill after that.”

Operating a bit like a balloon, teen dramas often start small in scope, then expand to encompass the most extreme of circumstances. Plots get dropped, characters — and nipple rings — disappear without explanation, and increasingly overwrought obstacles keep couples apart (@ the time **checks notes** Blair became Princess of Monaco on Gossip Girl). The high school years frequently fare best because the environment functions like a pressure cooker. When the world expands, tension deflates, and close-knit connections become endangered. In turn, writers’ rooms start to scramble. Yale acceptances get rescinded, with a newly mentioned, award-winning local college becoming the nexus for the next season’s plot. (See: California University on Beverly Hills, 90210.) Or a time jump catapults everyone to their mid-twenties, outfitted with new fiances, even spouses. (See: Lucas Scott, One Tree Hill, season five; Veronica Lodge, Riverdale, also season five.) Life pulls the group in question apart until the writers inevitably wrench them back together, a necessary act to preserve the genre’s driving force: its sense of community.

For me, tuning into the latest episode of a teen drama feels like spending time with friends in a way that trying to finally finish the first season of The White Lotus (which I’ve been inching through since December, for the record) does not. The cultural commentary might be well attuned, dialogue sharp, and plot expertly architected, but, if I don’t especially care about the characters, as is the case with so much of the prestige TV I’ve watched and tried to watch, then I struggle to see the point of spending 12+ hours with them. (That’s not to conflate care and investment with character likability; some of the most engaging teen drama characters are lovably unlikable. See: Blair Waldorf.) To many friends’ frustration, this lack of focus on my part often leaves me forgetting about compelling-on-paper content mid-season, all the while never falling more than a week or two behind on Riverdale or the Pretty Little Liars reboot.

As is the case with sitcoms, much of the teen drama’s appeal lies in its ability to sit the viewer down with a familiar crew for pie at The Peach Pit, coffee at Karen’s Cafe, a milkshake at Pop’s, one hour a week, year after year (or hour after hour, day after day, if you’re an after-the-fact binge watcher). The on-screen friend group withstands the test of time, staying connected against all odds and inviting the viewer into this imagined intimacy along the way. Growth occurs on and offscreen, creating a parallel interconnectedness between viewer and character, fact and fiction, in case of real-time watching over the course of years. Consequently, as I see it, the diminishing quality of these programs becomes tangential. Teen dramas aren’t in the business of well-crafted plots; they’re in the business of people and fun. Specifically, they’re in the business of building beloved characters, then placing them in extreme circumstances to see how they fare, taking viewers along for that ride.

Characters in teen dramas often feel things so deeply, so openly, that their unencumbered humanity creates comfort. Think of Dawson crying on the dock, an exhibition of extreme emotion for which we all probably have an unfortunate point of reference. Because of its absurdity, that cringe-inducing moment can feel cathartic in a way that watching a suited-up Don Draper smoke by an LA pool may not. A Refinery29 piece about why teen dramas handle grief so well points to “the period of time in the characters’ lives that we’re watching. Chalk it up to burgeoning hormones or the fear of growing up, but your teen years are rife with scary firsts and big emotions that can almost feel insurmountable.” Scary firsts naturally diminish with time, but big emotions never quite do; we just get better at either managing or masking them. So, as a 2014 NYU Local piece, “In Defense of ‘Crummy’ CW Shows,” put it: “While these shows border on the absurd, they never fail to be relatable.” In short, teen dramas give their viewers freedom to feel in the purest sense of the term.

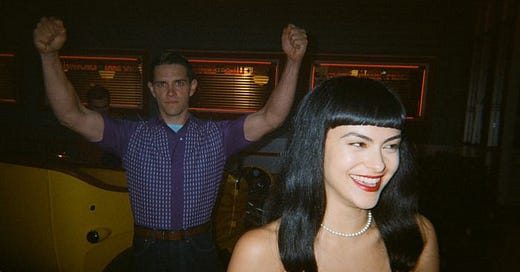

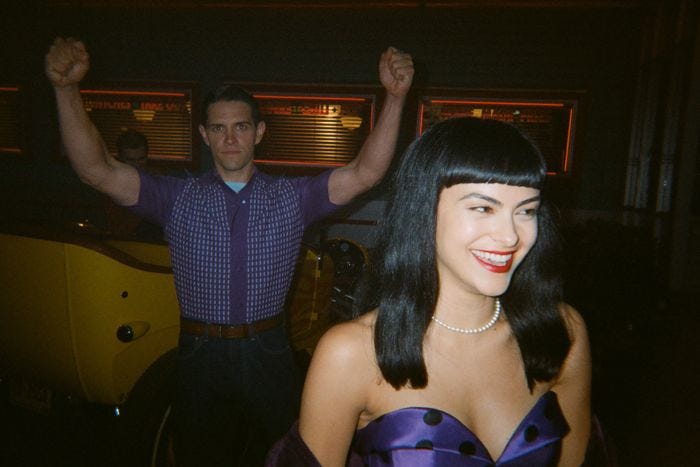

To watch a long-running, 22-episode-per-season teen drama is to spend time exploring the furthest corners of humanity — through the most ridiculous of lenses. During Variety’s “exit interview” with the Riverdale cast, Lili Reinhart said: “I think it’s important to acknowledge that our show is made fun of a lot. People see clips taken out of context. By 2019, “Riverdale Cringe” videos had become a genre online, be they TikTok reactions to particularly funny lines of dialogue or YouTube compilations of strange moments from the show and are like, What? I thought this was about teenagers. And we thought so as well—in season one…It is What the fuck? That’s the whole point. When we’re doing our table reads and something ridiculous happens, [showrunner] Roberto [Aguirre-Sacasa] is laughing because he understands the absurdity and the campiness.” TV Guide registers this reality in a recent piece, “Riverdale Was Too Ambitiously Bizarre to Ever Be Bad,” stating: “Riverdale never became a bad show; it became a different one, with different priorities, choosing fun and experimentation over the initial "Greek suburban tragedy" vibe that Betty identified at the end of Season 1.”

To that point, teen dramas are, above all, a great time. After watching the penultimate episode of Riverdale, I made my way to its subreddit to gauge viewer reactions and stumbled across one that stood out, a user who wrote: “This show has been a great joy to watch. It makes me feel like I’m a kid again…campy ideas, surprisingly good acting, and just plain fun.” Another user added: “We’re having FUN we’re being SILLY does this look like a hard-hitting HBO drama to you people.” These takes get to the core of something Schwartz said in his Vanity Fair interview about The OC: “For the people who love the show, they love it deeply.” Do I have my issues with certain teen drama plots? Absolutely. I still want a word with the One Tree Hill writers for most of what happened after season four, with whoever let Cole Sprouse and Lili Reinhart (seemingly) negotiate no-contact Riverdale contracts after their real-life breakup. But those grievances pale in comparison to the sense of community, permission for raw emotion, and sheer joy I glean from watching this genre, the same sensation I aspire toward creating through the prism of literary fiction.

The NYU Local piece’s author proudly asserts: “I’ve seen Emmy-winning shows, I’ve seen some of the greatest shows in the history of television, and I hate to say it, but I liked my run of The OC more.” I’d say the same about Riverdale, about all the shows of its kind that came before it.