A Look Back: September Book Review

Ripley Era™ (cont.), The Woman Artist™ (cont.), etc.

In September, I continued reading Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley series with Ripley’s Game (1974) before diving into my Didion and Babitz (2024) galley, McNally Editions’ reissue of The Stepdaughter (1976), a stunning new short story collection tied to a semi-fictional Australian serial killer, and Sarah Manguso’s latest novel, Liars (2024).

Let’s get into it:

Ripley’s Game by Patricia Highsmith (1974) — The third installment in Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley series inhabits a new narrative space, the mind of someone other than its eponymous con man.

Working class British picture framer Jonathan Trevanny lives a fairly happy existence in Fontainebleau with his French wife, Simone, and their son, Georges, save for the ticking time bomb of his leukemia diagnosis. Prior to the start of the novel, Jonathan makes the grave mistake of attending a party alongside Tom Ripley, of making a snide remark that Tom interprets as a slight. Six months have passed since the Derwatt episode detailed in Ripley Under Ground (1970), “a near-catastrophe from which he [Tom] had escaped with no worse than a bit of suspicion on him. Thin ice, yes, but the ice hadn’t broken through.” When American criminal Reeves Minot reaches out for help with a mafia hit, Tom — standing “taller, conscious of the fine house in which he live[s], of his secure existence now” — declines, eager to preserve the life built at his beloved Belle Ombre with his wife, Heloise, and their housekeeper, Mme. Annette. Tom instead points to Jonathan as a potential gun for hire.

Highsmith’s close third-person perspective shifts to inhabit Jonathan’s addled anxiety, where it stays for the bulk of the book, a true psychological thriller. Reeves’s initial outreach gets met with indignant rejection, despite the promise of a private consultation with a doctor in Hamburg. But, a rumor floating through Fontainebleau, one about his worsening condition, ultimately worms its way into Jonathan’s consciousness. He insists on additional tests from his doctor, hyperaware of every physical feeling (“Then close to 11 p.m., as they were about to go to bed, Jonathan felt a sudden depression, as if his legs, his whole body, had sunk into something viscous — as if he were walking hip-deep in mud. Was he simply tired? But it seemed more mental than physical.”). The breach between the mental and physical blurs, and, the more Jonathan stews on Reeves’s proposition, the more his moral fiber begins to fray.

Ripley’s Game, to me, marks the first morsel of genuine friendship Tom exhibits in the series. His hyper-fixation with Dickie Greenleaf in The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955) stems from an arguable combination of envy and lust, while his relationship with the Derwatt Ltd. team in Ripley Under Ground comes with a kind of professional distance. Tom’s contempt toward Jonathan, however, alchemizes into camaraderie. The two men move from opposite ends of the moral spectrum toward its center as the novel’s narrative accelerates toward its devastating conclusion, shaped as ever by Highsmith’s signature “elegant, amused, sophisticated sangfroid,” per Kirkus Reviews.

Didion and Babitz by Lili Anolik (2024) — I unsurprisingly had a lot to say about this one. You can check out my full review here if you haven’t already.

The Stepdaughter by Caroline Blackwood (1976) — This McNally Editions reissue reads like a creepy fairytale, one reimagined on the Upper West Side of the 1970s from the perspective of J., a new kind of evil stepmother (“I find Renata very ugly. I am therefore in no way jealous of her beauty, but in other ways my attitude toward her is much too horribly like the evil stepmother of Snow White.”) As writer Gideon Leek puts it in his LARB review: “Perched high above the traffic of the Upper West Side…she’s a nightmare in a nightgown, a mean spirit in a mink coat, an insult comic trapped in a high-rise.”

This slim epistolary novel consists of imaginary letters written by J. — notably, in her mind — to no one (“I am only writing letters in my head because I am jealous of the young French girl Arnold has sent over to me from Paris. Monique…writes real letters whenever she is given a moment’s peace to write them. My letters are written entirely out of rivalry, always end up as something unmailed and useless in my brain.”). J.’s husband, Arnold, has fled to Paris in pursuit of a younger woman and left her alone with their toddler, Sally Ann; an au pair, Monique; and his 13-year-old daughter from a prior marriage, Renata. An awkward child obsessed with making cakes from boxed mixes, Renata bears the brunt of J.’s artistic and romantic impotence (“The girl obsesses me. All the anger I should feel for Arnold I feel for Renata.”). J.’s grip on reality teeters and tips as the aperture of her husband’s abandonment sharpens.

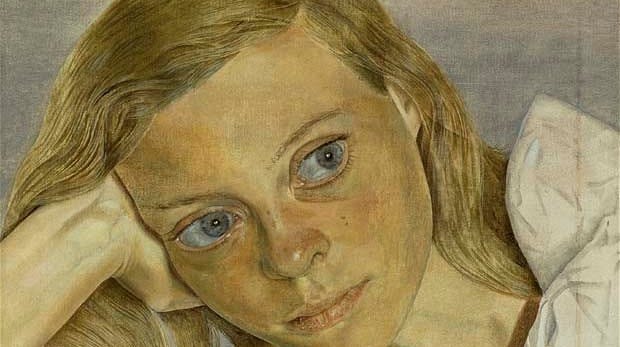

A few words on Lady Caroline Blackwood: A British socialite and artist, Blackwood grew up at her parents’ Knightsbridge home in London before flitting through a series of schooling experiences in Essex and Northern Ireland. A debutante, she entered London society in 1949, then went on to marry three creative giants: British painter Lucian Freud, Polish pianist Israel Citkowitz, and American poet Robert Lowell. Blackwood sat for a slew of paintings by her first husband — yes, grandson of Sigmund Freud — , who, per Leek, “introduced her to Picasso (who made a pass) and Francis Bacon (who contributed a recipe for mayonnaise to Blackwood’s 1980 cookbook).” The publication of her first book, a memoir titled For All That I Found There (1973), came at age 45, at the encouragement of Lowell. The question of Blackwood’s artistry perpetually loomed, distorted through the prism of her husbands’ reputations, each one’s fame often casting her as an indirect object to his omnipotent subject.

In The Stepdaughter, J.’s inability to paint propels her unhappiness as much as Arnold’s abandonment. She perpetually seeks the correct conditions to pursue her passion, unable to find them within and beyond the confines of marriage. In their prior apartment, J. had no space for a studio; in their new apartment, her studio becomes Renata’s room (“When he moved me into this new apartment, it was certainly not to give me better facilities for working, it was to give me better facilities for taking on the responsibility of the upbringing of Renata.”).

Arnold’s abandonment further suffocates J.’s creative drive, guts it in the absence of her “husband and the world…[to] think it clever and charming if…[she] got out…[her] palette and…[her] easel at all.” With Arnold gone, painting emerges as a potential vocation instead of a low-stakes hobby, psychologically paralyzing her pursuit. J. explains: “It may well turn out that my painting was only something that it was possible for me to do within the context of a marriage. When I was married to Arnold, I was able to regard my painting as a delightful creative hobby, that could be pursued on and off, without any particular intensity or professional seriousness.” The absence of that creative outlet seems to spur J.’s mental unspooling, and letters to no one emerge as her new art form.

Blackwood constructs J.’s inner world with scathing observations shaped by detail-rich prose (“Although superficially she [Renata] was very little trouble to me — she troubled me from morning to night. It is difficult to describe how she manages to be so disturbing, this Humpty Dumpty of a girl. She gives one the feeling that somewhere in the past she took such a great fall that everything healthy in her personality was badly smashed. She seems to be crying out for someone — let it be the King’s Horses, let it be oneself — to make some effort to put her together again.”). Odd, specific features get magnified through the lens of J.’s vision, from Renata’s cake mix fixation to a police officer’s “scarlet neck which looked as if it had absorbed more experience than his face…every inch of its weatherbeaten surface decorated by the most unpleasantly elaborate lithography of deep cracks and creases, which were all overlaid by a feathery tissue of spider-web lines.”

Second-wave feminism serves as the novel’s narrative backdrop. J. maintains distance from her female friends, noting: “I also find it distasteful when not only Martha, but also Dodo and Rita and Alice, and the rest of my women friends, seem only to long to be allowed to rally around me like the crowds that collect around a street accident.” Condescension comes cloaked in the disguise of faux concern, nosiness masquerading as “sisterhood.” As the story draws to a close, J.’s friend, Martha, finally makes an appearance at the apartment. She peddles unprompted pity, victimizing J. without her consent (“Martha then told me that it was obviously too early for me to be able to see my life in any perspective.”). This exchange reframes J.’s isolation, contextualizes how and why she has allowed “this apartment to become…[her] only life.”

Highway Thirteen by Fiona McFarlane (2024) — Fiona McFarlane opens her new short story collection with an epigraph from William Shakespeare’s Richard II (1595): “Each substance of a grief hath twenty shadows.” Highway Thirteen then continues with a glimpse into twelve such shadows of grief, distinctive stories spanning from 1950 through 2028, from Bristol to Austin to Sydney. Each narrative strand connects to a string of serial killings in 1990s Australia, loosely based on Ivan Milat’s 1989 reign of terror. Forms vary, from first to third person, from traditional prose to mock podcast script. As Kirkus Reviews describes: “The criminal investigation never becomes the central plot; the killer himself, here called Paul Biga, remains offstage while his victims appear only in fleeting mentions or glimpses.”

Through her narrative structure, McFarlane examines the ethics of how our collective culture consumes true crime. In an interview with The New Yorker, she explains: “One of the ethical concerns raised by retellings of serial murders is that the killers themselves become mythic figures, steeped in a glamorized notoriety. So I wanted to think about true-crime storytelling that didn’t center the killer. It’s possible to assemble a profile of the murderer by reading all the stories in ‘Highway Thirteen,’ but he rarely appears, he never really speaks, and his crimes aren’t described in detail. The book isn’t about why serial killers do what they do; it’s about the ripple effects in the lives of people who are one or two or five or fifty steps removed from those horrors.”

The strongest stories, from my perspective, have tighter emotional ties to the murders. For instance, in “Demolition,” an older married couple, Gerald and Eva Forsythe, watch the Biga house get demolished next door. Navigating an interview on the subject with true crime author Kate Hawkins, a kind of Courtney Cox in Scream (1996) stand-in, Eva reflects on her mixed feelings; while the public has reassigned its meaning, the space, for her, maintains an association with earlier occupants, the Laineys. Meanwhile, Austin-set “Abroad” teases out trauma experienced by a Bristol-born victim’s now-adult little brother, while “Hostel” drops into the perspective of a woman whose friends, now-divorced couple Roy and Mandy, crossed paths with two of Biga’s victims. As freelance book critic Mary Ann Gwinn describes in her LA Times review: “McFarlane is a master at just about everything: dialogue, setting, comic timing…But her biggest accomplishment is creating an empathic bond with people whose lives are touched by unexplainable violence.”

Liars by Sarah Manguso (2024) — Sarah Manguso’s newest novel opens with the following meditation: “In the beginning I was only myself. Everything that happened to me, I thought, was mine alone. Then I married a man, as women do. My life became archetypal, a drag show of nuclear familyhood. I got enmeshed in a story that had already been told ten billion times.”

The book then goes on to chronicle the dissolution of Jane, a writer who gradually loses herself in the role of “wife and mother,” in her marriage to John (“very much his own creep, but also quite generic,” per author Brian Dillon’s New York Times review). John voices an initial inability to commit that Jane overlooks, blinded by the sheen of new love (“In the beginning, everything about him had shone, but as time passed, I noticed that he used the word phenomena as a singular noun, couldn’t spell the word necessary, couldn’t write a coherent paragraph.”). Her idealization of him, of their relationship, supplants its reality, and that fantasy constructs her cage (“The reality I wanted didn’t include this event, so I stepped around it and continued on.”).

John’s immaturity and indecision propel their family through a series of cross-country moves, relocations punctuated by losses and layoffs, while Jane’s de-prioritized career dims. Dillon goes on: “What class of monster is John? Let me count his grisly ways. There are the dominating facts of his adultery, his definitive abandonment of Jane and the industrious untruth that goes with such ventures. But long before the end of their marriage he has been an exhausting object choice. He borrows $8,000 from Jane to make a movie and doesn’t pay it back; as his fortunes expand, he mocks her for not making enough money; he criticizes one of her books in company, saying she should have followed his advice about its structure; he tells people about her time in a psychiatric ward; he blames her for his own depression; he throws up his hands at tiny disappointments (the life model at his drawing class is a man!) and lounges about playing video games; he wants to know why his wife is so much angrier than other women.” Manguso distills the emotional murkiness that can define motherhood; suppressed anger toward John consumes Jane, while care for their son — “the child” — muddles her feelings into a more diluted cocktail.

In a recent piece for The Sewanee Review, author Hannah Bonner aptly characterizes Liars as a marital allegory, noting parallels to the book of Genesis. Similarities emerge on the levels of line and narrative, from Manguso’s pointed repetition of “in the beginning” to the gender roles that shape the book’s tension. John has his own egregious quirks, but Jane’s anger at the thanklessness of her life transcends this specific story (“I had become unable to articulate certain feelings. And so my body became their cultivation dish.”). She comes to embody a kind of quiet rage that generations of women have confronted, Betty Friedan’s “problem that has no name.” Bonner writes: “John and Jane become a twenty-first-century Adam and Eve whose story has ‘been told ten billion times’ but here, with Manguso’s clarity and candor the tragedy is not lyrically adorned but brutally rendered and plain.”

Brief vignettes shape the novel, a structure similar to Manguso’s first book, Very Cold People (2022), which I reviewed back in July. As Bonner describes: “Told in clipped, perfunctory prose, Liars exemplifies constraint: each short paragraph is a perfect, clenched fist.” This flavor of first-person prose, one propelled by tightly controlled fury, holds similarities to Elena Ferrante’s Days of Abandonment (2002), which delves into the psyche of Olga, a stay-at-home mother in her late 30s whose husband, Mario, leaves her for a younger woman. The novel opens with: “One April afternoon, right after lunch, my husband announced that he wanted to leave me. He did it while we were clearing the table; the children were quarreling as usual in the next room, the dog was dreaming, growling beside the radiator.” As I wrote back in April, “the ensuing 200ish pages trace the disintegration of the relationship through the prism of Olga’s grief, anger, and confusion, culminating in a rhythmic novel awash in mood.” The same characterization could apply to Liars, as both stories capture the categorical problem of power in marriage through a set of specific circumstances, animating the disorientation that comes with a relationship’s disintegration.

That’s all for now! Stay tuned for the September Movie Review.

xo,

Najet