Feud (Didion vs. Babitz)

On Lili Anolik's Upcoming Book and the Question of the Woman Artist™

I don’t typically post standalone reviews, but my thoughts on Vanity Fair contributor, Once Upon a Time…at Bennington College podcaster, and Eve Babitz biographer Lili Anolik’s new nonfiction book, Didion and Babitz (2024), have unspooled enough to warrant it.

Part of the sparkle that shapes an Anolik project stems from her approach to storytelling. Anolik — much like Eve, the subject of her “intense fascination” — understands the power of gossip, which informs the language that shapes her podcasts, articles, and books. In Didion and Babitz, she writes: “‘Haven’t you heard about Noel Parmentel Jr.?’ he [Dan Wakefield] asked after I read him the relevant portion of the letter.’ ‘No,’ I said. ‘Oh, well Noel Parmentel Jr. was the great love of Joan Didion’s life.’ I leaned in and cupped an ear. Say what and say who?” Over audio and in text, Anolik addresses the reader directly, cultivating a kind of parasocial closeness that propels readability (“In other words, Reader: don’t be a baby.”).

So, as Anolik might say, let’s get into it, Reader.

On December 17, 2021, Eve Babitz dies. Five days later, on December 23, 2021, Joan Didion follows suit. (A quick order of business — I’ll be referring to Eve and Joan by their first names throughout this piece, abandoning the archetypal formality of last names in literary criticism because, to me, both women feel like old friends.)

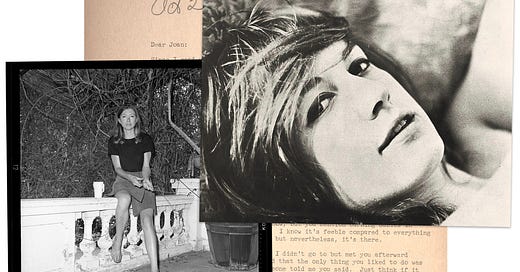

A week later, Eve’s sister, Mirandi, calls Anolik and asks her to join an excursion to The Huntington Library and Gardens in Pasadena, which had acquired Eve’s archives. Anolik goes. Upon arrival, she finds a string of letters, including an unmailed one addressed to Joan; an excerpt reads: “It embarrasses me that you don’t read Virginia Woolf. I feel as though you think she’s a ‘woman’s novelist’ and that only foggy brains could like her and that you, sharp, accurate journalist, you would never join the ranks of people who sogged around in The Waves. You prefer to be with the boys snickering at the silly women and writing accurate prose about Maria [Wyeth, from Didion’s second novel, Play It As It Lays (1970)] who had everything but Art.”

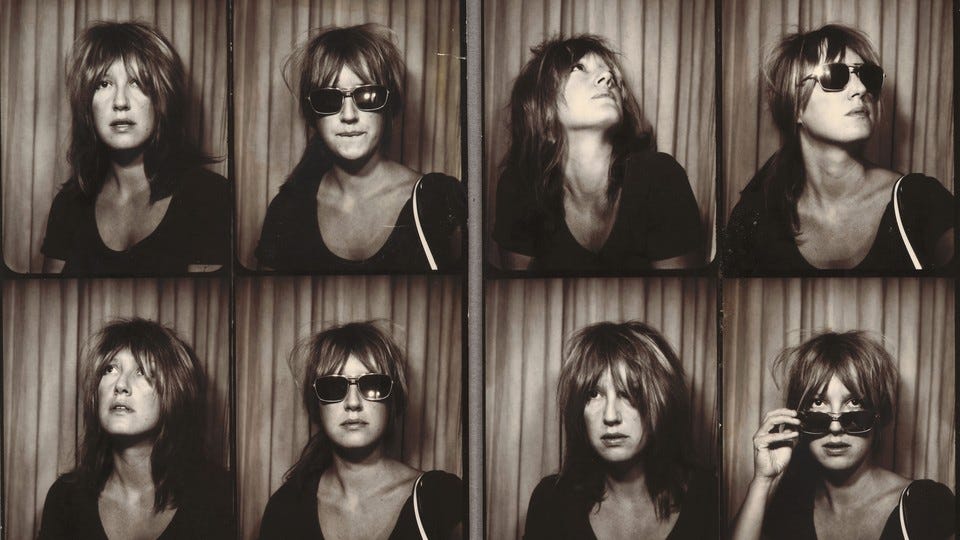

Eve embodies fire, excess, where Joan epitomizes ice, control. Eve participates. Joan critiques. Joan approaches Los Angeles as an outsider, a “native daughter” of the Central Valley’s Sacramento. Eve inhabits LA as an insider, “a low-high, profane-sublime bohemian aristocrat by birth.” Each woman wrenches her readers’ minds toward a specific vision of the city, one opposed by her counterpart’s texts.

Per the May newsletter, Eve “basks in her unabashed love of Los Angeles (‘The Bloody Marys at Musso & Frank’s Restaurant are unparalleled in Western thought and can cure anything.’). In Slow Days, Fast Company, her most critically acclaimed work…[she] writes: ‘I love L.A. The only time I ever go to Forest Lawn is when someone dies. A kid from New York once said: ‘Look. Which would you rather? To spend eternity looking out over these pretty green hills or in some overcrowded ghetto cemetery next to the expressway in Queens?’ L.A. didn’t invent eternity. Forest Lawn is just an example of eternity carried to its logical conclusion. I love L.A. because it does things like that.’” Meanwhile, Didion enacts a darker version of Los Angeles; take, as an example, her second novel, Play It As It Lays (1970), a Seconal-laced look at the entertainment industry, a professional sector synonymous with the city itself. As Anolik puts it, “with Play It, Joan was, in Eve’s view, pandering to the chauvinism of New Yorkers, telling them what they wanted to hear — sucking up, basically. (Why sucking up? Because New York ruled the roost high-culture-wise. If you hoped to make it as a serious writer, it was New York you had to impress.) How could Eve see Play It as anything but a flagrant act of betrayal by a native daughter [of California]?”

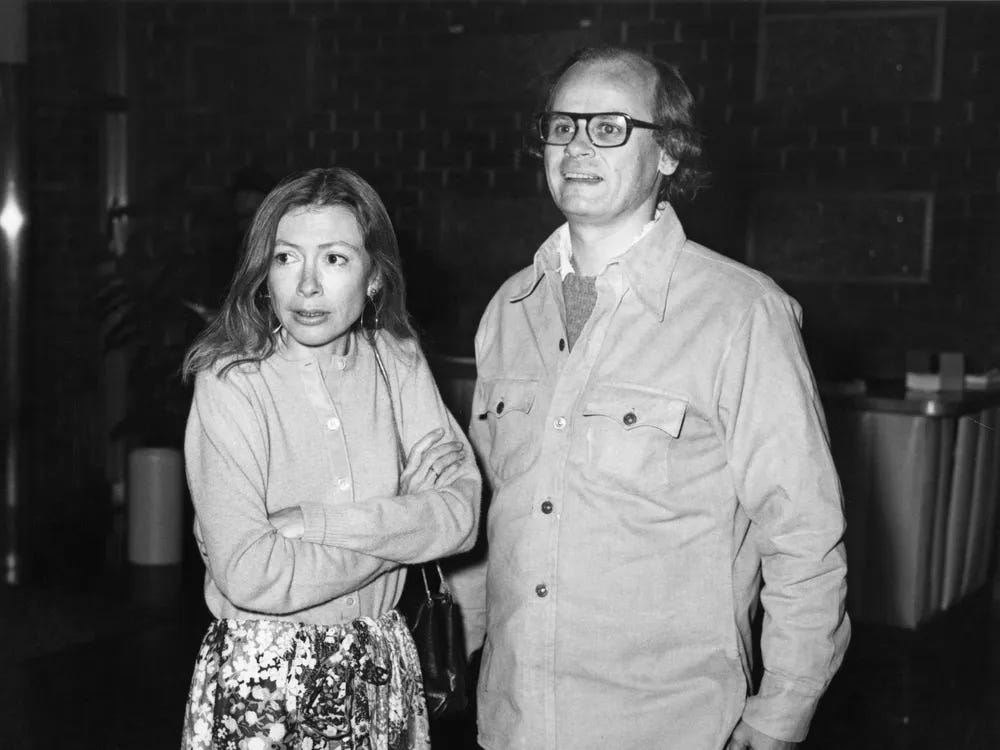

In Didion and Babitz (2024), Anolik explores Eve and Joan’s equally potent, tonally distinctive iterations of artistry (“Joan was an alchemist. The pain of life became the gold of literature once she ran it through her typewriter. Eve, on the other hand, was repelled by sadness, wanted nothing whatsoever to do with it.”). She holds a magnifying glass to their respective career paths, relationships with men (and, in Eve’s case, a few women, including Annie Leibovitz), and shared social circle, dubbed “the Franklin Avenue scene” for Didion’s 7406 Franklin Avenue address, a nexus for the likes of Harrison Ford, Michelle Phillips, and Susanna Moore from 1966 through 1971.

The book unravels the notion of the “woman artist” through the dual lenses of Eve and Joan, dissects the factors — whether familiar, romantic, or societal — that shape form and fortune. One of the most interesting examinations, from my perspective, centers on their differing approaches to long-term partnership and how it shapes their work, their legacies.

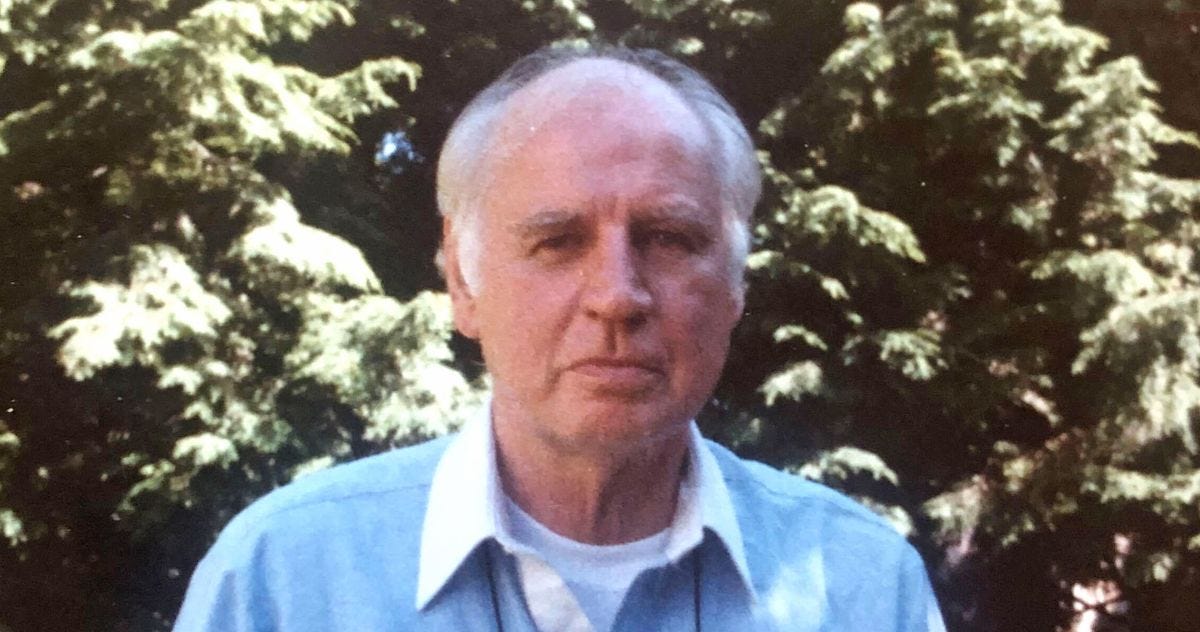

Anolik unearths Noel Parmentel Jr. as Joan’s first great love. Her initial literary advocate, Parmentel pushes for the publication of her debut novel, Run River (1963). As writer and one-time Babitz boyfriend Dan Wakefield explains to Anolik: “‘Noel’s the one who told me about Joan because Noel was telling everyone about Joan…He was like a super-agent. He’d just go up to people and make the case for Joan until they listened. He really made it happen for her.’”

Parmentel makes “it happen” for Joan not only professionally, but also romantically. He ultimately introduces her to John Gregory Dunne, a man who offers the kind of stability he lacks, as well as a heightened version of the support to which Joan had grown accustomed (Per Parmentel: “‘He’d be at the breakfast table every morning, something I’d never be. And he’d edit her line by line.’”). As Anolik explains: “Dunne was an acolyte of Parmentel’s and therefore understood the deal, all the ways in which Joan required cosseting and coddling. He could be counted on to take over as her custodian since he’d been de facto groomed for the job.” Parmentel remains a close friend of the Didion-Dunnes until Joan excises him in her third novel, The Book of Common Prayer (1977), but, in 1964, something cracks just the same.

In her essay about leaving New York, “Goodbye to All That,” published as part of Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968), Didion famously writes: “All I mean is that I was very young in New York, and that at some point the golden rhythm was broken, and I am not that young anymore.” Middling reviews of Run River contribute to this feeling, but her breakup with Parmentel breaks that “golden rhythm” in equal measure, their dual weight sweeping her into an undertow, toward Los Angeles.

Where Joan needs “cosseting and coddling,” Eve — despite being more emotional, more sensitive — does not. For those of you unfamiliar with her work, as I lay out in the May newsletter:

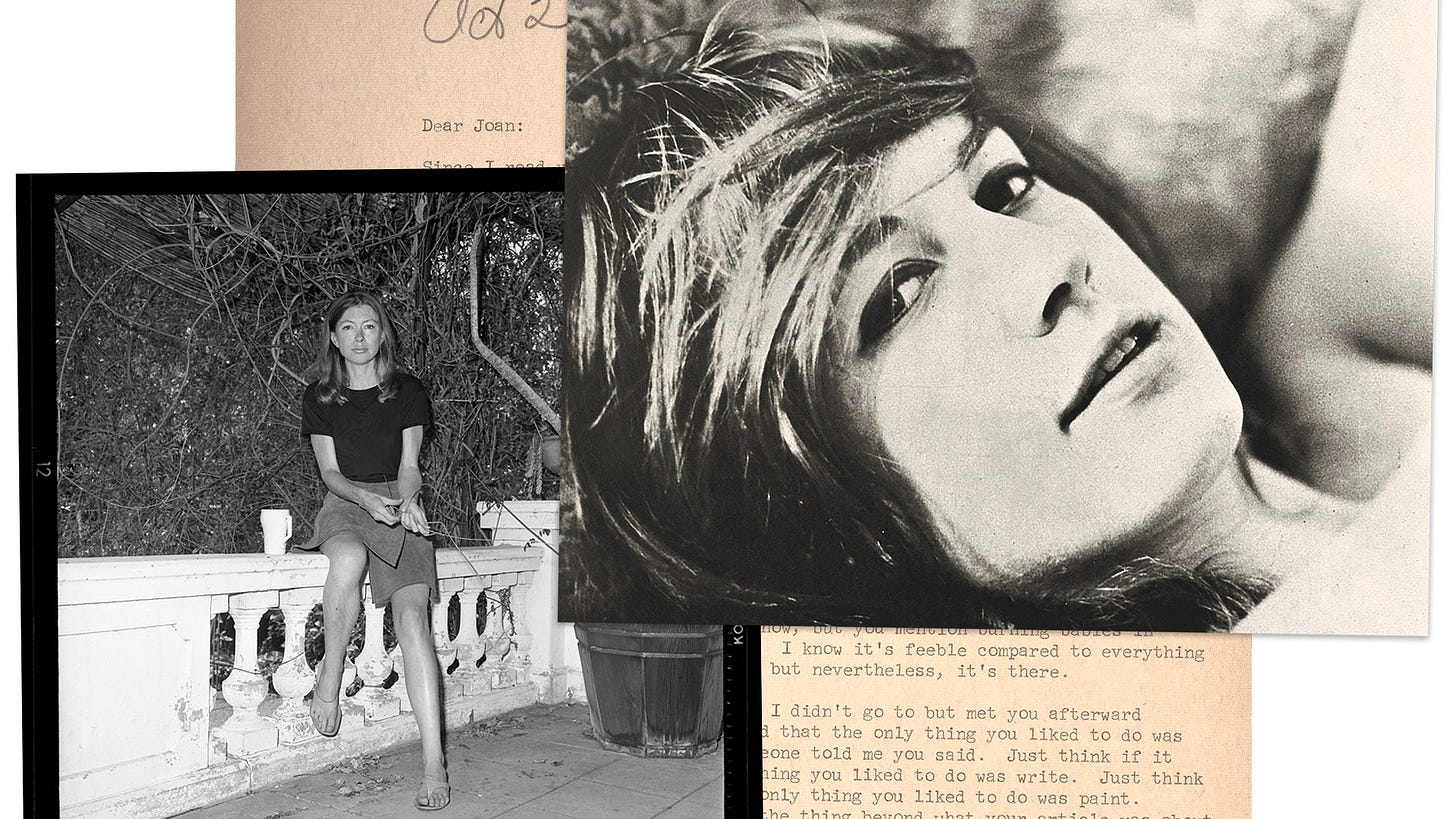

Babitz grew up in Los Angeles in the 1950s and early 1960s, where she attended Hollywood High School. Her first shot of notoriety came in 1963 at age 20, when Time’s Julian Wasser photographed her playing chess in the nude with Marcel Duchamp at the Pasadena Art Museum, a move on Babitz’s part to make her married boyfriend, museum director — and former co-runner of Ferus Gallery, where Andy Warhol’s soup cans made their West Coast debut — Walter Hopps, jealous. She toggled between art world and music scene groupie, hooking up with everyone from Paul Ruscha to Jim Morrison (Per Eve’s gay frenemy Earl McGrath: “In every young man's life there is an Eve Babitz. It's usually Eve Babitz.”). She also created cover art for some of the most iconic musicians of the 1960s and 1970s, including Linda Ronstadt, The Byrds, and Buffalo Springfield.

All the while, Babitz recorded her misadventures in writing, and her career took a fortuitous turn when she befriended Joan Didion. In the early days of what would become a lifelong frenemyship, Didion advocated for Babitz’s work, leading to the publication of Eve’s Hollywood in 1974. Babitz’s writings trace the cultural evolution of Los Angeles from the 1960s through the 1990s in essay collections and novels including Sex and Rage (1979), L.A. Woman (1982), and Black Swans (1993); as Matthew Specktor puts it in his introduction to the New York Review Books reissue of Slow Days, Fast Company (1977): “I can think of no cultural artifact of any kind that better preserves Sunset Boulevard, circa 1974.”

Where Joan works best with a partner, Eve enacts a solitary kind of artistry, an ironic inversion given Joan’s tendency toward observation, Eve’s penchant for participation. But under the shadow of Joan, of the Didion-Dunnes’ powerful partnership, a certain pressure emerges, and Eve moves her sexual focus from artists and musicians toward fellow writers in hopes of finding her own John Gregory Dunne.

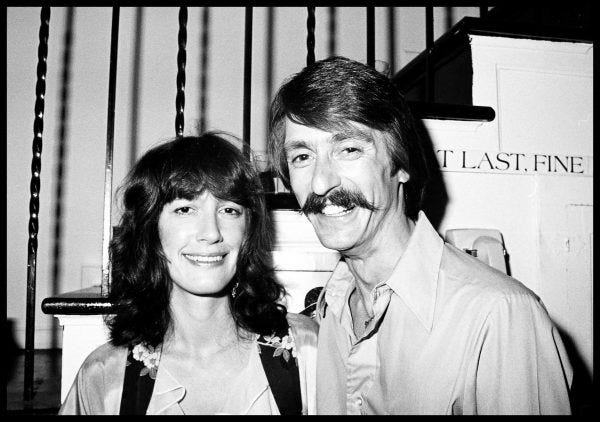

One attempt: Dan Wakefield. As Anolik explains: “What I imagine she [Eve] saw when she looked to Joan: a person who’d worked out the problem of being a female artist. Joan’s solution? Take for a mate a male artist. By choosing Dan Wakefield, Eve was, whether she knew it or not, imitating Joan.” But Eve fails to find the same kind of support that defines the Didion-Dunne marriage; she recounts: “Rolling Stone had just turned down something of Dan’s…As soon as I told him they were going to publish my piece, he dumped me. And he fucked my friend. ‘I’ll see you on Johnny Carson.’ That’s what he said to me when he walked out the door.”

Another attempt: Grover Lewis. Anolik writes: “Grover Lewis was, in so many ways, Dan Wakefield Redux: another writer/editor, another boyfriend/husband, another potential John Gregory Dunne. ‘I’ve always associated San Francisco with retirement,’ said Eve. ‘So I moved there to become a square…Nobody in San Francisco threw parties. But I threw parties left and right. It drove Grover to nervous breakdown. I think I bowled him over. I couldn’t help it. I’m much too huge for some people.’” As Mirandi Babitz recounts in Didion and Babitz, Lewis turns abusive toward Eve, and she helps her sister return to LA.

While Eve ends up alone in the traditional sense of the term, her partnership with Paul Ruscha informs the structure of what I — and many — consider her magnum opus: Slow Days, Fast Company. Per the May newsletter:

Eve Babitz’s iconic Southern California essay collection opens with the following: “This is a love story and I apologize; it was inadvertent. But I want it clearly understood from the beginning that I don’t expect it to turn out well…Since it’s impossible to get this one I’m in love with to read anything unless it’s about or to him, I’m going to riddle this book with Easter Egg italics so that this time it won’t take him two and half years to read my book like it did the first one. The seduction of a non-reader is how I plan to tie up L.A.. Virginia Woolf said that people read fiction the same way they listen to gossip, so if you’re reading this at all then you might as well read my private asides written so he’ll read it. I have to be extremely funny and wonderful around him just to get his attention at all and it’s a shame to let it all go for one person.”

The subsequent writings meander across and beyond Los Angeles; to Bakersfield (“There was no extra energy in those women beyond their children or their particular geography. There was no energy for humor or wit, and I wondered at my friends in L.A. who were always brimming over with spare words and bright phrases.”), Palm Springs (“I wanted to write a story about Palm Springs that was going to be sexy. I wanted a story with peace in it, for god’s sake. Now I was stuck with this broken romance: Shawn kissing my foot instead of my mouth.”), and Emerald Bay (“Dead leaves must have been removed from trees before they dried up so that no one would ever have to think about things drying up and falling to the ground in Emerald Bay. No unpleasant notions.”). Epigraphs to the object of Babitz’s affection, Paul Ruscha (yes, brother of Ed), precede each essay (“Darling: I know you don’t are about the art of the novel but you might like the part about Forest Lawn.”), creating a thematic through line. But each piece stands on its own, pierces the core of California’s cultural zeitgeist (“You can’t write a story about L.A. that doesn’t turn around in the middle or get lost.”).

But inspiration from a partner differs from stylistic codependence. Where Joan relies on Dunne to “edit her line by line,” Eve resists the notion of anyone peddling with her prose regardless of relationship status or gender. “‘I hate people who tell me what to do to improve my stuff. They get nowhere with me,’” Eve explains. Following Playboy editor Jim Goode’s well-intentioned — but ill-fated — attempt to firm up her short story, “The Sheik,” Eve receives an offer from the Didion-Dunnes to edit Hollywood’s Eve (1974) after Joan has already helped secure the debut book deal. Sensitivity subsumes Eve, and she ultimately rejects that editorial mentorship in its early stages, declaring to their shared circle that she has “fired” Joan. From there, contempt, a one-way current, builds.

In her unsent letter, the spiel that sets off Anolik’s narrative, Eve writes: “For a long, long, long time women didn’t have any money and didn’t have time and were considered unfeminine if they shone like you do Joan. Just think, Joan, if you were five feet eleven and wrote like you do and stuff — people’d judge you differently and your work, they’d invent reasons…Could you write what you want to write if you weren’t so tiny, Joan? Would you be allowed to if you weren’t physically so unthreatening? Would the balance of power between you and John have collapsed long ago if it weren’t that he regards you a lot of the time as a child so it’s all right that you are famous. And you yourself make it more all right because you are always referring to your size.”

Joan’s solution to the problem of female artistry — her willingness to strategically defer to men, to traditional marriage, to the East Coast literary establishment — cements her legacy as a Great Writer, capitalization intended. Meanwhile, in 1997, Eve retreats from public life after accidentally dropping a lit match on her skirt, catching her stockings and skin on fire; then, with age, Huntington’s Disease eats away at her mind. These terrible twin fortunes couple with her compulsive self-reliance, with her refusal to play ball, and Eve flies under the radar — until she doesn’t.

Anolik profiles Eve for Vanity Fair in 2014, then develops a full-blown biography, Hollywood’s Eve (2019), which Didion disciple Bret Easton Ellis characterizes as: “A gossipy and wonderful introduction to not only Eve Babitz and her somewhat tragic life…but the social history of Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s—[a] jeweled piece of pop culture.” Her books get reissued, and she becomes a beloved figure among a certain kind of extroverted intellectualista, “a totemic figure, particularly to women in the arts, the ones who understand from experience what she went through,” per Anolik.

Didion and Babitz closes with Anolik’s assertion that “Eve, with her string of storied lovers, and Joan, with her storied marriage, were both alone.” She identifies them as a kind of artistic yin and yang, two parts of a whole vision of Los Angeles. I agree, to an extent; to me, the specific texture of their solitude differs. Where Joan experiences emotional isolation swaddled with constant editorial support, Eve casts aside her patrons — and pays the price until Anolik ushers in that unlikely renaissance. (You could argue that Anolik embodies Eve’s eleventh hour embrace of a patron, but, really, she filled the role of fan, a well-connected one who offered Eve a microphone.) Eve and Joan offer two imperfect answers to the question of the woman artist; by laying their choices bare, Anolik helps literary descendants present and future pick their poison.

Didion and Babitz publishes on November 12, 2024. You can preorder here.

Thanks for alerting me to this upcoming book. I'm finishing up my own essay on Didion's nonfiction, will be posting it soon.