Movies of the Month: July [2024]

On New Hollywood and the optimism of the United States Bicentennial, the final film in Richard Linklater's Before trilogy, and Brian Eno

In July’s (Extremely Late) film round-up, we have thoughts on the final third of Richard Linklater’s Before trilogy and the Brian Eno documentary now entering its eighth week at Film Forum. But, first, we need to discuss Rocky (1976).

Let’s get into it:

Rocky (1976, dir. John G. Avildsen) — Let’s just say the quiet part out loud; this watch was obviously a somewhat off-brand one for me because sports even if 1970s cinema; I saw Sylvester Stallone’s sequel-spawning classic with my mom over Fourth of July.

A Philadelphia-set Cinderella story, Rocky centers on its eponymous boxer who, per The New York Times’s 1976 pan, “due to circumstances too foolish to go into, is granted the opportunity of his lifetime. He is given a chance to fight the heavyweight champion of the world, a black fighter named Apollo Creed (played by Carl Weathers), modeled on Muhammad Ali so superficially as to be an almost criminal waste of character. It's not good enough to be libelous, though by making the Ali-like fighter such a dope, the film explores areas of latent racism that just may not be all that latent.” Simultaneously, Rocky pursues his crush, Adrian (played by Talia Shire), “an incipient spinster who comes late to sexual life,” per The New York Times ca. 1976.

Ultimately, I was Not the Target Audience for this movie, but I’m glad I watched it for a couple of reasons. First, what a banger of an opening title sequence. Second, during one of the episodes of The Bret Easton Ellis Podcast featuring Quentin Tarantino on the occasion of Cinema Speculation’s publication last fall, the two discuss the movie. With Tarantino’s book focused on New Hollywood, part of their conversation centers on how Rocky (1976) offered a bright glimmer of hope to then-contemporary audiences who had grown accustomed to grim endings a la Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Days of Heaven (1978), etc. Taken in that context, coupled with the big fight getting tied to the United States’s Bicentennial, I found Rocky a compelling capsule of American culture in 1976, of the combination of nihilism and optimism that seemed to define that particular year.

Roger Ebert notes this notion of the film as a then-welcome answer to national exasperation and ennui in his review, writing: “What makes the movie extraordinary is that it doesn’t try to surprise us with an original plot, with twists and complications; it wants to involve us on an elemental, a sometimes savage, level. It’s about heroism and realizing your potential, about taking your best shot and sticking by your girl. It sounds not only clichéd but corny — and yet it’s not, not a bit, because it really does work on those levels. It involves us emotionally, it makes us commit ourselves: We find, maybe to our surprise after remaining detached during so many movies, that this time we care.”

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video (premium subscription)

Before Midnight (2013, dir. Richard Linklater) — In discussing Richard Linklater’s Before trilogy from the vantage point of the third film, Ethan Hawke is widely quoted as saying: “The first film is about what could be, the second is about what should have been. Before Midnight is about what it is.” [ICYMI: I reviewed both Before Sunrise (1995) and Before Sunset (2004) in the June Movie Review.]

**spoilers ahead for Before Sunrise and Before Sunset*

Where Before Sunrise harnesses the limitless possibility of youth, and Before Sunset shows the regret of roads not taken, Before Midnight teases out the feeling of banality that can come to accompany a chosen path. Before Midnight picks up nine years after the events of Before Sunset, after Jesse (played by Ethan Hawke) famously, baby, missed that plane. He chooses to forego returning to the United States, to his wife and son, in favor of a life with Céline (played by Julie Delpy), and Before Midnight holds a magnifying glass up to the complications of that choice, to what that life looks like.

Set over a family holiday in Greece, the film shows Jesse and Céline vacationing with their twin daughters (played by Jennifer and Charlotte Prior) and a collective of friends after sending Jesse’s now-teenage son, Hank (played by Seamus Davey-Fitzpatrick), back to his mother in Chicago as summer comes to a close. The couple, as always, meanders and chats, with their conversation coalescing into the crescendo of a hotel room fight this time. As film critic Peter Bradshaw notes in his 2013 review for The Guardian: “The situation is acted out with terrific clarity and gusto by Hawke and Delpy, who wrote the screenplay with Linklater.”

As Pablo Villaça observes in his 2013 review for RogerEbert.com: “It would be easy to build a romanticized third chapter to serve as the climax for the previous two, but Linklater, Delpy, and Hawke choose instead to look at Jesse and Celine as a mature couple. The film offers an appropriate and natural view on the experience of a consummated love…The mutual idealization of the past has been replaced by comfort in each other’s presence — and also with an underlying, perfectly understandable irritation. Before, they could only guess what was going on in each other’s minds. Now Jesse and Céline have a PhD in Céline and Jesse, respectively. They can be lethal in discussion because they know exactly where to hit; which old wound to squeeze; which sour memory of the past to dredge up, and when.”

Before Midnight, to me, operates as the ultimate movie about marriage. It dissects what happens when romance takes a backseat to responsibility; Villaça characterizes the film as “moving because it acknowledges that even love stories that began as beautifully as Jesse and Céline’s must still endure the wear and tear of real life.” At one point, as the pair strolls together, Jesse comments: “How long’s it been since we wandered around bullshitting?” This question connotes a cornerstone of their relationship as a now-intermittent privilege and, in doing so, reinforces the notion of long-term love as unwavering commitment, an idea that comes to define the film and, ultimately, the trilogy.

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video ($3.59)

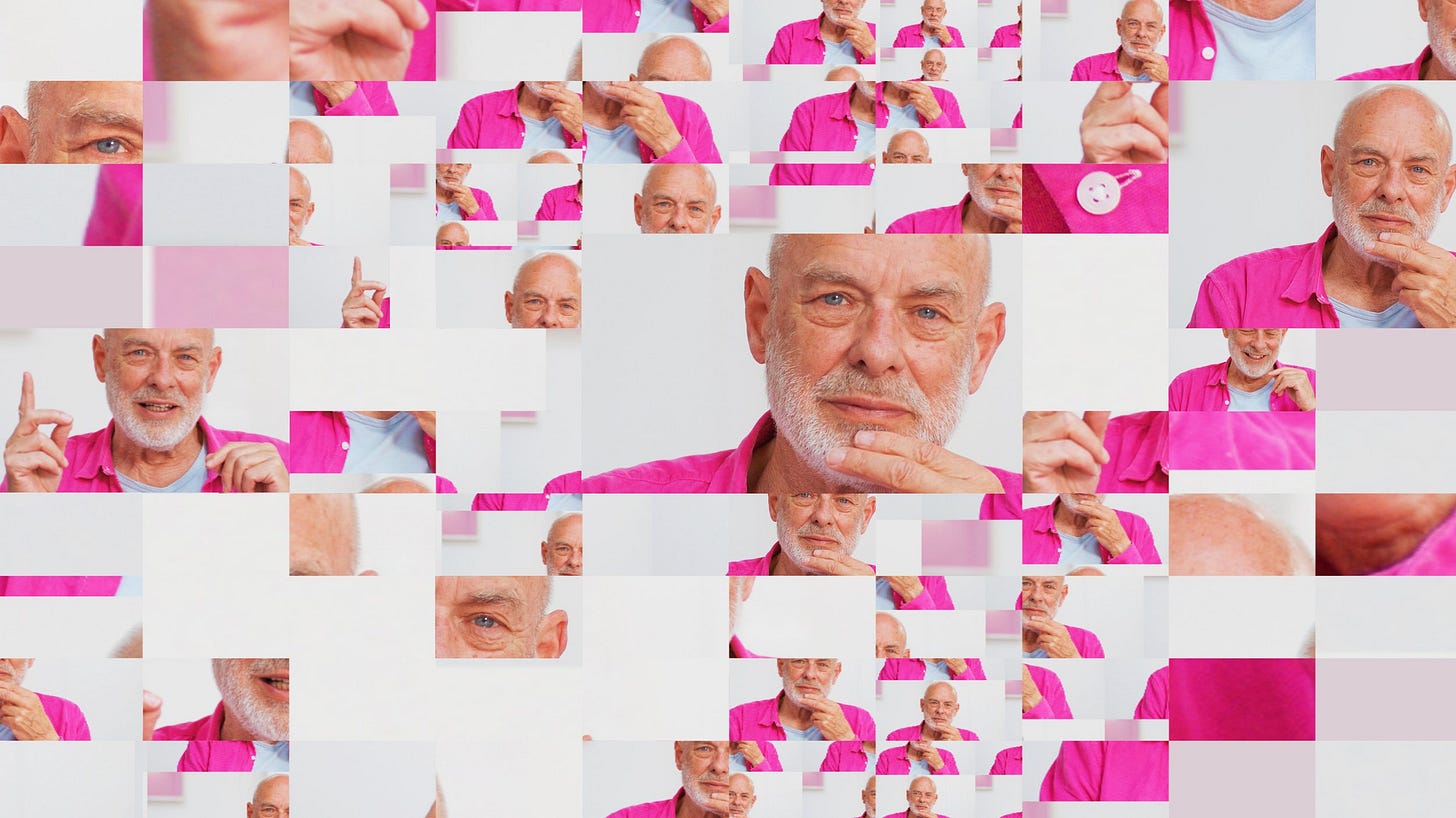

Eno (2024, dir. Gary Hustwit) — I feel especially badly that this review is late because Film Forum’s screening of Eno (2024), now in its eighth week, wraps this coming Thursday. But hopefully, this documentary, which lives up to its 100% Rotten Tomatoes score, was already on the radars of any New York-based Brian Eno fans and subscribers from the July newsletter. As I wrote then:

Directed by Gary Hustwit, this documentary about Roxy Music member and Gen X god Brian Eno premiered at Sundance to rave reviews back in January…It opens at Film Forum later this month, with a computer program set to live edit the film so that a different version plays at each screening.

In his Rolling Stone review, David Fear writes: “Brian Eno — former Roxy Music member, legendary recording producer, Berlin-era Bowie bestie, ambient music pioneer, and a man who rocked a Seventies kimono like no other — is not someone who likes dwelling on the past or being pinned down. The idea of a movie chronicling his 50-year career behind the keyboards and mixing boards, much less one involving his participation, feels counterintuitive to him…Hustwit proposed something different. He’d been talking to a programmer about software that would be able to remix film footage in real time. The feature would be fully edited and completed, mind you. But if you ran the work through this program, it would rejigger the order of the sequences at random. Certain scenes would be ‘pinned’ at the beginning and the end, per the director. Everything else, from the chronology to what was or was not included within a two-hour timeframe, could be left to chance…Applied to a conceptual musician like Brian Eno, who couldn’t play an instrument when he joined Roxy Music but took up the synthesizer because it was new and thus ‘there were no rules on how not to play it,’ the approach feels like it might be the only way to properly talk about Eno.”

The structure of the documentary, as Fear notes, emerges as the filmic equivalent of Eno’s experimental approach to music-making. (ICYMI: Eno considers himself a generative musician, one who believes in creating “a system or a set of rules which, once set in motion, will create music for you.”) The friend I went to this film with in July revisited it in August and saw an entirely different version. Per The New York Times, Hurstwit’s “collaborator, the digital artist and programmer Brendan Dawes, explained that because of the variables, including 30 hours of interviews with Eno and 500 hours of film from his personal archive, there are 52 quintillion possible versions of the movie. (A quintillion is a billion billion.)”

Within each version of the film, certain vignettes recur, while others appear only once. Hustwit and Dawes flatten the importance of the various events that comprise Eno’s life, creating a perpetual present tense that echoes the musician’s insistence that: “I don't live in the past at all; I'm always wanting to do something new. I make a point of constantly trying to forget and get things out of my mind.”

Where to Watch: Eno closes at Film Forum on 9.5! It’s also playing in Nashville and San Francisco this week. Then, you can check out details around future screenings on filmmaker Gary Hustwit’s website here; the film notably opens in Boston and LA in late September.

Stay tuned for the August Movie Review!

xo,

Najet