A Look Back: February Book Review [2024]

The girlies are not okay // also Tarantino on New Hollywood

A month of books about Being a Woman and also Tarantino’s Cinema Speculation.

Let’s get into it:

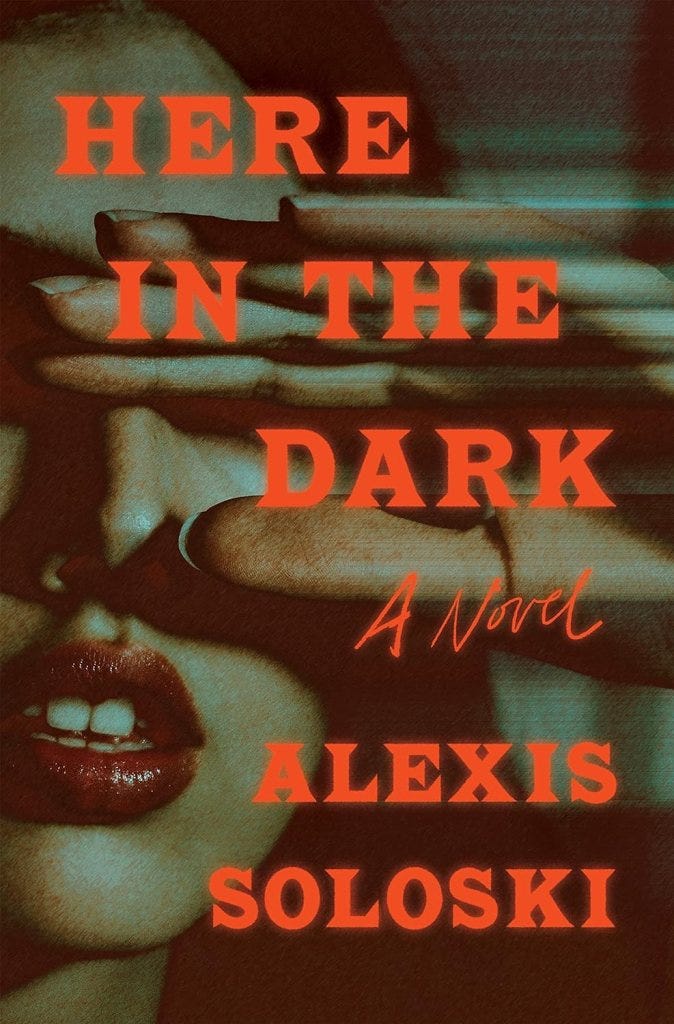

Here in the Dark by Alexis Soloski (2023) — This new novel from Alexis Soloski exemplifies the richness that can emerge when an author writes what they know. Soloski serves as a culture reporter at The New York Times, previously held the lead theater critic position at The Village Voice, and has an MFA in Theater from Columbia University. All that to say, she understands the nuances of the New York theater world, an inherent grasp that makes her debut especially visceral.

Here in the Dark centers on junior theater critic Vivian Parry, a woman in her early 30s with a My Year of Rest and Relaxation-esque proclivity for self destruction. She keeps everyone around her at arm’s length — save for her best friend, Justine — and spends her spare time drinking, popping pills, and generally waiting for the time between performances to pass. Her routine existence experiences a jolt when, per the front flap, “angling for a promotion, she reluctantly agrees to an interview on her style and methods, a conversation that reveals secrets she had long buried. Then her interviewer disappears and Vivian learns — from his devastated fiancé — that she was the last person to have seen him alive.” As she seeks answers, Vivian finds herself thrust deeper and deeper into the unnerving underbelly of the downtown theater scene.

In Vivian, Soloski crafts a hard-boiled stream of consciousness, the kind of narration you might expect from a 1940s detective novel rather than 2020s genre fiction. As New York Theater put it: “Here in the Dark is more Dashiell Hammett than Dorothy Parker, the central character as much Sam Spade as Addison DeWitt.” For instance, Vivian narrates: “Instead he alternates my columns with those of the other junior critic, Caleb Jones. Caleb has a newly minted dramaturgy MFA, a retina-scarring smile, and the aesthetic discernment of a wedge salad. Me, I have taste for days. And a brisk, prickly, style. Roger will see sense. Eventually.” Consider how Soloski uses commas to slice her sentences, to create an abrupt internal dialogue (“Me, I have taste for days. And a brisk, prickly, style. Roger will see sense. Eventually.”). Vivian’s “brisk, prickly style” — a hallmark of her work, of her identity — gets not only told, but also shown through the sharp quality of the novel’s first-person prose.

The culture of downtown New York shapes the tone and tenor of the narrative, operates as a kind of character in and of itself (“Canal Street judders with cars and people and the cries of hawkers peddling rambutan and dragon fruit, the bristling red-pink skins jabbing at the gray sky.”). For me, the vivid, immersive quality of Vivian’s narration makes this novel an undeniably propulsive read, outweighing the story’s more outlandish flourishes. Per Kirkus Reviews: “It's worth at least pretending to suspend disbelief and ride out Vivian's Lost Weekend death spiral for whole slew of reasons — fun supporting characters (a louche actress best friend, a flamboyant receptionist at Vivian's magazine), ultra-snappy dialogue and metaphors, rough sex (if you like that sort of thing), and finally an over-the-top payoff that neatly pulls all the wild threads together, followed by a totally impossible but nonetheless touching denouement. Like Dorothy Parker, the narrator's role model, this book is almost too clever for its own good.”

The Best of Everything by Rona Jaffe (1958) — Valley of the Dolls (Corporate Remix), The Best of Everything takes its name from The New York Times’s advertisements to young women at the height of the 1950s:

YOU DESERVE THE BEST OF EVERYTHING

The best job, the best surroundings,

the best pay, the best contacts.

The novel opens with that promise, the siren call of “having it all” as its epigraph, then spends the ensuing 400+ pages cracking open the mirage it creates.

The narrative initially focuses on three young women working in the typing pool of Midtown publishing house Fabian Publications — Westchester sophisticate and former Radcliffe girlie Caroline Bender, Colorado country bumpkin April Morrison, and aspiring actress Gregg Adams — before widening its aperture to encompass a broader chorus. Jaffe meanders through the lives of various women in and around Fabian, capturing an earnest snapshot of the era’s emotional texture through a decidedly female lens. As The New Yorker puts it: “Rona Jaffe’s best-seller from 1958, is what you would get if you took Sex and the City and set it inside Mad Men’s universe…it has the white-gloved, Scotch-swilling aesthetic of the fifties but also an unflinching frankness about women’s lives and desires — a combination that makes it feel radical, prescient.”

In her 2005 foreword, Jaffe writes: “I didn’t know if the things that happened to my friends and me were an anomaly, so I interviewed fifty women to see if they’d had the same experiences, with the men and the jobs and all the things nobody spoke about in polite company. Back then, people didn’t talk about not being a virgin. They didn’t talk about going out with married men. They didn’t talk about abortion. They didn’t talk about sexual harassment, which had no name in those days. But after interviewing these women, I realized that all these issues were part of their lives too. I thought that if I could help one young woman sitting in her tiny apartment thinking she was all alone and a bad girl, then the book would be worthwhile. I had no idea what a chord it would strike for millions.”

The Best of Everything earnestly distills the timeless preoccupations of a certain (read as: mostly white, upper middle class) sect of women, of the kind of postgrad who pops out of Katharine Gibbs and onto Madison Avenue in the 1950s and runs through Madison Square Park with her (girl)boss’s incredibly specific matcha order in the 2010s. At times, the plot wanders a bit too much, from my perspective; for instance, Jaffe focuses on Gregg fairly heavily, far beyond her exit from the publishing house, while relegating other (IMO more compelling) Fabian girlies to only a few chapters. Marriage, though, often emerges as the common end block, begging the question of whether these early exits, in actuality, reflect a precise societal truth rather than a scattered literary vision.

Cinema Speculation by Quentin Tarantino (2023) — If you’ve ever wanted to grab a drink with Tarantino, buy this book. As I put it in the March newsletter, Cinema Speculation “serves as a reflection on his personal experiences with 1970s cinema, an ode to the films that shaped his taste as a little boy growing up in Los Angeles. Conversational in nature, Tarantino’s prose creates the experience of sitting down with him over a couple of cocktails, getting his takes on well- and lesser-known films that formed the landscape of New Hollywood.”

The opening essay, “Little Q Watching Big Movies,” sets the collection’s tone. Tarantino reminisces about tagging along with his mother to the movies at a turning point in film history, the late 1960s, when the studio system began to implode. He writes: “On the ride home, even if I didn’t have questions, my parents would talk about the movie we had just seen. These are some of my fondest memories. Sometimes they liked the movie and sometimes they didn’t, but I was usually a little surprised how thoughtful they were about it.” The ensuing essays harness that framework established in his youth, taking a casual yet thoughtful look at everything from what would have happened if Brian De Palma had directed Taxi Driver to second-string film critic Kevin Thomas as The LA Times’s longtime secret weapon to what distinguishes the Movie Brats (Scorsese, Spielberg, Lucas, etc.) from their forefathers. I closed this book with an intricate understanding of late 20th Century Hollywood and an even more intricate to-watch list.

Dead Weight: Essays on Hunger and Harm by Emmeline Clein (2024) — This debut’s prologue opens with the following: “Have you ever seen a girl and wanted to possess her? Not like a man would…possess her like a girl or a ghost of one: shove your soul in her mouth and inhabit her skin, live her life? Then you’ve experience girlhood, or at least one like mine. Less a gender or an age and more an ethos or an ache, it’s a risky era, stretchy and interminable.” Clein (who, in the interest of full disclosure, went to college with me) spends the ensuing pages weaving a nuanced portrait of “hunger and harm” in the United States, one that entwines external research with individual experience to reveal the systemic factors that fuel the eating disorder economy.

To me, the singularity of Dead Weight stems from its scope and prose. The book examines the cultural and sociopolitical influences that perpetuate what Kirkus Reviews calls “this insidious phenomenon,” from Goop’s role in promoting orthorexia to the myth of the “it girl” to the addictive pull of Weight Watchers. Clein draws on research, testimonials, and the stories of historical and fictional figures from Catherine of Siena to Blair Waldorf, her touchstones spanning eras and mediums to cultivate a sense of solidarity. For instance, she writes: “Marissa Cooper, with her hidden vodka bottles and torrid affairs, chasing oblivion in The O.C., is not so different from the young heroines of Jean Rhys novels, drinking their way through the bars and hotel rooms of European cities.” Across the various essays, Clein also underscores the inherent danger that lurks within the idea of the skinny, straight, white girl with an eating disorder, an image cemented in our collective cultural conscience; she emphasizes the trouble with this notion’s singularity, how it marginalizes overweight, LGBTQ+, and BIPOC people navigating analogous struggles.

Clein takes a novelistic approach to nonfiction, one that culminates in an “urgent, intense, and often captivating” style, per Kirkus Reviews. Her prose seduces with the second person, collapses the space between author and reader. To conclude the prologue, she writes: "Can I tell you a story that isn’t mine? I’m going to be doing that a lot, but it’s because I can’t tell where you stop and I start, or I don’t think it matters, not when we’re locked on the same ward. Besides, so many of our stories are so similar, I slipped into yours in my dream last night, and you’re welcome here whenever you want. Let me make you a drink and tell you about someone you might have been.”

That’s all for now! Stay tuned for the February Movie Review in the coming days.

xo,

Najet