I saw five new releases — Anora (2024), Bogart: Life Comes in Flashes (2024), Wicked (2024), Heretic (2024), and Maria (2024) — in November, plus an Ealing comedy at Film Forum and Pablo Larraín’s Jackie (2016).

Let’s get into it:

Anora (2024, dir. Sean Baker) — Pretty Woman (1990) meets After Hours (1985), Sean Baker’s latest film inhabits Brooklyn’s Eastern European-dominant community of Brighton Beach. The narrative centers on Anora “Ani” Mikheev (played by Mikey Madison), a tough-talking twenty-three year-old stripper at a Midtown club. When a customer requests a Russian-speaking dancer, Ani gets introduced to Ivan “Vanya” Zakharov (played by Mark Eydelshteyn), the hard partying 21-year-old son of a Russian oligarch. The pair gets sucked into a whirlwind romance, complete with day after day languishing in Ivan’s Brighton Beach mansion and a joyride to Vegas. But their sexual and domestic bubble bursts with the arrival of Toros (played by Karren Karagulian), Garnick (played by Vache Tovmasyan), and Igor (played by Yura Borisov), a trio of henchmen sent by Ivan’s father, launching Ani on an odyssey through and beyond Brooklyn. As Patrick Gibbs writes in his Slug Mag review: “Nothing about this story…should be humorous, yet most of Anora is a fast and furious comedy that borders on screwball farce.”

Mikey Madison stuns as Ani, the film’s final moment the crown jewel of her performance. In her review for The New York Times, movie critic Alissa Wilkinson writes: “Anora is a bawdy modern fable, populated by strippers and strongmen and brutes. Like most of Baker’s movies, it is, at its core, about the limits of the American dream, the many invisible walls that stand in the way of fantasies about equality and opportunity and pulling yourself up by your bootstraps. This is a story of wealth, and power, and what love can and can’t overcome. But it’s also about something far more heart-rending: what it means to be accustomed to being looked at one way, and then experiencing, out of the blue, what it feels like to actually be seen.” That feeling of “actually be[ing] seen” softens Ani’s hardened exterior, which seems to crack once and for all in the closing scene.

Without spoiling specifics, the endings of Anora and Wim Wenders’s Perfect Days (2023) strike me as tonally similar, emotional releases pitched at different registers. In his review of the latter film, The Hollywood Reporter’s Chief Film Critic, David Rooney, writes: “Wim Wenders ends his eloquent and emotionally rich Japanese drama, Perfect Days…held tight on the extraordinarily expressive face of Koji Yakusho as his character drives through Tokyo reflecting on the rewards and perhaps also the regrets of his life…The song that this resolutely analog man is listening to on his car cassette player is a Nina Simone standard that has become one of the most overused tracks in contemporary movies. But it fits the scene so precisely and captures the way in which the character moves through his small pocket of the world with such exactitude, it feels almost like hearing the song for the first time.” Meanwhile, Anora ends in near-silence — a quieter, more melancholic exhale, but an exhale nonetheless.

Where to Watch: ~a theater near you~

Bogart: Life Comes in Flashes (2024, dir. Kathryn Ferguson) — This new documentary about screen legend — and my favorite Hollywood Golden Age actor — Humphrey Bogart had its limited release a few weeks ago. As I write in the November newsletter, “told entirely in his own words and blessed by his estate, the film threads together Bogart’s legacy through the lens of his relationships with the five women who had the biggest impact on his life — his mother and four wives, including my girl Lauren Bacall.”

Shaped by previously unseen archives, letters, and interviews, Bogart: Life Comes in Flashes (2024) is a must see for any big fans of the late actor. For anyone else though, I’d probably recommend skipping this one and picking up Lauren Bacall’s memoir, By Myself and Then Some (2005), which offers up much of the same information in far better packaging, instead.

Filmmaker Kathryn Ferguson intercuts archival images with odd sequences of headless present-day actors intended to elicit the historical backdrop of Bogart’s various relationships, from Broadway backstage in the 1920s to Hollywood home life in the 1950s. This aesthetic choice, to me, kills the documentary’s visual quality, making the 100-minute movie difficult to watch no matter how compelling the content.

Where to Watch: ~a theater near you~

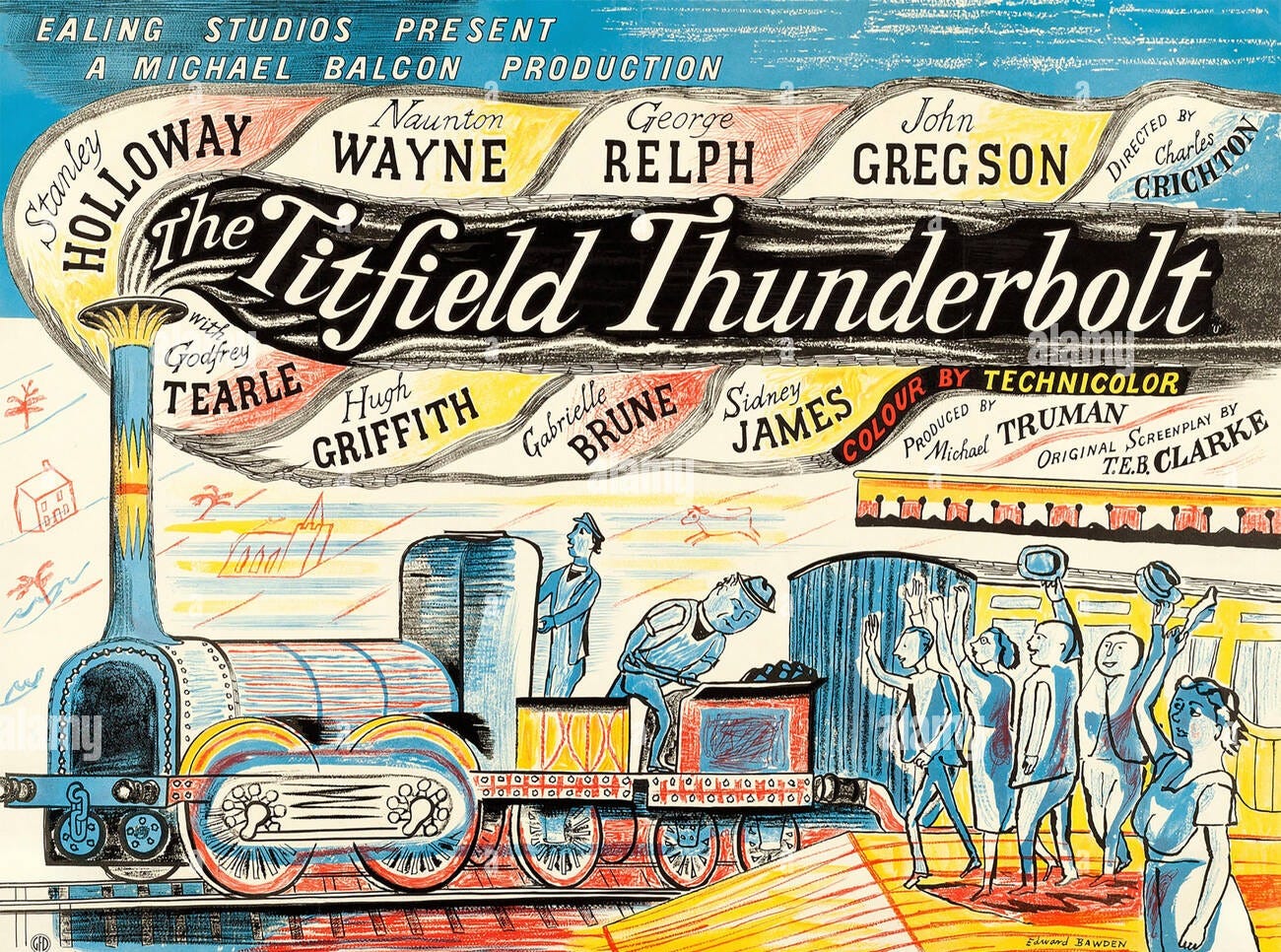

The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953, dir. Charles Crichton) — In November, Film Forum mounted a festival dedicated to Ealing Studios. Per the site: “Producer Michael Balcon (discoverer of Hitchcock and grandfather of Daniel Day-Lewis) created, through the family atmosphere he fostered at his suburban London Ealing Studios, a body of work as distinctive as any classic genre: The Ealing Comedy, featuring the farcically ingenious plots of writer T.E.B. Clark, the wry direction of Charles Crichton, Robert Hamer, and Alexander Mackendrick (who’d go on to make the rather un-Ealing Sweet Smell of Success), and a world-renowned stock company of eccentrics including Margaret Rutherford, Stanley Holloway, Alastair Sim, Joan Greenwood, and especially Alec Guinness, who stars in five films (in twelve different roles) in the series.”

A quintessential example of the Ealing comedy, The Titfield Thunderbolt (1953) focuses on a group of villagers striving to keep their local train line open after British Railways announces its impending closure. The locals decide to operate the station privately, and slapstick shenanigans — from a local bus line rivalry to an antique locomotive theft — ensue as the narrative builds toward a deliciously dry conclusion. As film critic Cleaver Patterson writes: “Shot in dazzling Technicolor (the film was the first time the studio had used the process), the train and bucolic countryside through which it steams spring from the screen with a wonderful vibrancy and depth, captured by the legendary cinematographer Douglas Slocombe who went on to work on such classics as Anthony Harvey’s The Lion in Winter (1968) and Steven Spielberg’s Indiana Jones films during the 1980’s.”

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video (premium subscription), The Roku Channel (premium subscription)

Wicked (2024, dir. Jon M. Chu) — I really went into this movie prepared to be a hater. The marketing blitz preceding its premiere struck me as so over the top (see: Vulture’s breakdown of the most egregious stunts) and manufactured (see: bizarre integrations with The Bachelorette). Plus, its stars’ press interviews exuded the worst kind of cringe theatre kid energy. As E.J. Dickson, Senior Culture Writer at The Cut, puts it:

Many on social media found [Ariana] Grande and [Cynthia] Erivo’s behavior puzzling…But as someone who went to a performing-arts camp for four years, I can tell you exactly what’s going on here. Grande and Erivo are behaving the exact same way the two leads in your senior-year production of Legally Blonde do when they’re in tech rehearsals and carrying vocal rest whiteboards and they’re finally realizing that one of them is going to Carnegie Mellon next year while the other is going to BoCo. It’s a level of psychic stress that no one who has [sic] been outside that situation can really understand, akin to undergoing combat training in the Marine Corps or attending a Renaissance Fair with a bunch of fire eaters who have done too many mushrooms. It’s a world that is so grueling and insular that it truly feels like there’s nothing outside the universe of your show and your castmates. In fact, if I were interviewing Grande and Erivo on the press tour, I’d probably ask them if they knew the results of the presidential election. I’d bet money they don’t, and you know what? Why should they? They were busy holding space for “Defying Gravity.”

Unfortunately though, I had the time of my life. Five stars (okay, four and a half if you’re fact checking on my Letterboxd), no notes.

ICYMI: Wicked (2024) — based on the 2003 Broadway musical from Stephen Schwartz, based on the 1995 novel by Gregory Maguire — essentially operates as elevated Wizard of Oz (1939) fan fiction. It traces the hidden history of a friendship between Glinda the Good Witch (played by Ariana Grande) and The Wicked Witch of the West, Elphaba (played by Cynthia Erivo). The narrative begins with Elphaba’s death by water bucket at the end of The Wizard of Oz, then returns to the school days that shaped both witches. It disrupts the notion of an official narrative, tackling themes ranging from animal rights to government corruption to, of course, female friendship.

Maximalism marks the opening number and first few sequences. Filmmaker Jon M. Chu’s showmanship never fully fades, but, as the narrative unfolds and gains nuance, it feels less obtrusive. In his Vulture review, film critic Bilge Ebiri aptly writes: “When things do occasionally quiet down, the actors shine. With her pagoda-roof eyelashes and her quicksilver physicality, Grande gives real comic shape to Glinda’s popular-girl frivolity. She also pokes fun at her own terrific vocal range, tossing errant high notes into simple statements like ‘I already have a private su-iiite.’ Erivo arguably has the harder task. Elphaba is the one who goes from rejection and sadness to love and stridency and, finally, rage.” From my perspective, Erivo embodies each emotional beat, delivering a powerful performance that fuels the heart of the film.

The supporting cast — which includes Jonathan Bailey (I guess I need to watch Bridgerton now?), Jeff Goldblum (who has no business wearing a green tux as well as he does here), and Michelle Yeoh — matches this caliber. As Christy Lemire writes in her RogerEbert.com review: “[Filmmaker Jon M.] Chu's usual choreographer, Christopher Scott, delivers…with vibrant, inspired moves, particularly in the elaborate ‘Dancing Through Life,’ which takes place in the school’s rotating, multilevel library. Bridgerton star Jonathan Bailey gets a chance to show off his musical theater background here, and he's terrifically charming as the glib Prince Fiyero, the object of both Elphaba and Galinda’s romantic interests. Michelle Yeoh brings elegance and just a hint of danger to her role as Madame Morrible, the university's sorcery professor. And Peter Dinklage lends gravitas as the resonant voice of Dr. Dillamond, a goat instructor who, like other talking animals in Oz, finds himself increasingly in peril.”

Wicked (2024) covers the Broadway musical’s first act, with part two slated to hit screens next fall. It still clocks in at two hours and 40 minutes, a running time I thought unconscionable until I actually saw the film; the length breathes depth into the story and characters, layering onto the spackle of the stage production.

Where to Watch: ~a theater near you~

Heretic (2024, dir. Scott Beck and Bryan Woods) — This A24 thriller from the team behind A Quiet Place (2018) opens with a pair of Mormon missionaries, Sister Barnes (played by Sophie Thatcher) and Sister Paxton (played by Chloe East), preparing to visit a list of people who have previously expressed interest in learning more about the LDS Church. They start with Mr. Reed (played brilliantly by my rom-com king, Hugh Grant, in another against-type turn), a reclusive Brit with a Boulder home out of Hansel and Gretel. He invites the pair inside for a slice of blueberry pie, the snack of choice being prepared by his wife in the next room. The trio discusses the veracity of religion, and Reed reveals his position as a skeptic before leading Sister Barnes and Sister Paxton into a much darker debate.

TLDR, per my Letterboxd review, Heretic (2024) ultimately proved too scary for me (and also just devolved into rote horror at a point), but I’m glad my boy Hugh was having a good time. On casting him, filmmaker Bryan Woods tells The Hollywood Reporter: “We [Woods and Scott Beck] just felt so strongly that it had to be Hugh, especially after revisiting all of his work in the last 10 years and this character actor journey that he’s been on, starting with Cloud Atlas (2012) to playing an Oompa-Loompa in Wonka (2023). The bizarre risks that he’s taking are insane and really inspiring.” In Heretic, Hugh embodies a disarmingly endearing British Norman Bates, an older one moonlighting as a r/atheism moderator. (Woods tells GQ: “I've never seen anything as in-depth as Hugh's process. We spent four months in pre-production emailing each other essays back and forth. He would write, like, ‘Does Reed come from this part of the world,’ and ‘Does he think this,’ and we'd answer back…when I say that out loud, it almost sounds obnoxious, but it was actually a lot of fun.”)

In a discussion with GQ, Woods goes on: “Scott and I…[were] like, ‘We’re gonna weaponize 20 years of his relationship with the audience, particularly in the first 30 minutes.’” And weaponize they do. Manohla Dargis, Chief Film Critic for The New York Times, opens her review as follows: “One of the great benefits of watching too many movies are all the life lessons they impart. For instance, if your host mentions that the walls of his house happened to be lined with metal, you should immediately feign a headache and split before he closes the front door. If the windows in his house look too small even for a child to squeeze through, you should also exit. And if there’s also a framed image of hell on a wall, you should definitely conk him on his head and run. That said, if the host is played by Hugh Grant, you may want to stick around.” His charm, even served with a chill, carries the film.

While Hugh’s performance consistently stuns, Heretic itself, from my perspective, starts off strong, then sputters. Without spoiling specifics, Sister Barnes discovers something toward the start of their visit that inverts the reality Reed has carefully constructed for them, inciting a compelling sense of claustrophobia. Philosophical debate, peppered with off-kilter pop culture references, propels the opening hour. For example, Reed paints the LDS Church as Bob Ross Monopoly to overarching Christianity’s mainstream Monopoly, delves into Radiohead’s 2018 copyright lawsuit against Lana Del Rey to decry the world’s religions as derivative. But, as Reed lures Sister Barnes and Sister Paxton deeper into his home, discussion dwindles in favor of stereotypical scary movie tropes and special effects.

Where to Watch: ~a theater near you~

Maria (2024, dir. Pablo Larraín) — This biopic from Chilean filmmaker Pablo Larraín marks the third in his series about iconic 20th Century women, with Jackie (2016) and Spencer (2021) as its predecessors. The film follows the final week in the life of Maria Callas (played by Angelina Jolie “in a queenly performance of poise and mystique,” per Tomris Laffly for Roger Ebert.com), the famed Greek opera singer who retreated from performance and public life in her final years.

I went into Maria (2024) knowing nothing about its namesake and left transfixed. A bit about her life: Born in New York, Maria Callas relocated to Athens with her mother and sister as a child. Under the city’s German occupation, Callas’s mother put her daughters to work, relying on them to bring home money and food. Per a 1956 Time interview: “‘I'll never forgive her,’ she [Callas] says, ‘for taking my childhood away. During all the years I should have been playing and growing up, I was singing or making money. Everything I did for them was mostly good and everything they did to me was mostly bad.’ Mrs. Callas had moved back to Athens…In 1951 she wrote Maria to ask for $100, ‘for my daily bread.’ Answered Maria: ‘Don't come to us with your troubles. I had to work for my money, and you are young enough to work, too. If you can't make enough money to live on, you can jump out of the window or drown yourself.’”

Callas felt unloved, far from beautiful, as a young girl. The Time piece, which ruffled feathers for its focus on the singer’s troubled relationship with her mother, continues: “‘My sister was slim and beautiful and friendly, and my mother always preferred her. I was the ugly duckling, fat and clumsy and unpopular. It is a cruel thing to make a child feel ugly and unwanted.’ Forced to wear heavy spectacles for her myopic eyes, little Maria avoided schoolmates, ate compulsively (sometimes a whole pound of cheese at breakfast).” Her voice became her source of power. She performed with the Greek National Opera throughout World War II, making her lead debut in 1942.

After the Axis occupation of Greece ended, Callas traveled to the United States to visit her father, then began performing in Italy, where she met her first husband, Giovanni Battista Meneghini, a well-off industrialist 27 years her senior. Her breakthrough came in Venice in 1949; established Italian opera singer Margherita Carosio fell ill, and Callas stepped in as her understudy. She learned the role of Elvira in I puritani in less than a week, and the performance launched her toward global fame. Callas went on to perform in La traviata, Medea, and Anna Bolena, among other operas, around the world.

In 1957, following a party given in her honor after a performance of Anna Bolena, Callas met Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis (yes, of Jackie Kennedy Onassis). Within a matter of years, she and Onassis left their respective spouses and embarked on an affair that would continue until his 1975 death. They never married, and their relationship carried beyond Onassis’s 1969 second wedding to former First Lady Jackie Kennedy. His longtime personal secretary Kiki Feroudi Moutsatsos tells People: “He couldn’t live without Maria…He had succeeded in getting married and having next to him the First Lady of the United States. He was a businessman…[but] they [Onassis and Callas] never stopped seeing each other. Never.”

Eventually, Callas lost her singing voice. Per History.com: “In the 1960s, Callas’s iconic range began to falter. ‘At times, she couldn’t hit the high notes and didn’t know why when the day before or after she could,’ [Cast a Diva: The Hidden Life of Maria Callas author Lyndsy] Spence says. When Callas began to cancel shows, critics and fans pounced: ‘When she sang in Copenhagen, audience members said, ‘let’s go home and listen to our Callas records, she’s a shell of herself,’ says Spence. ‘Callas had positioned herself as the best, and she pushed herself and her coworkers so hard in her prime that there was no room for mistakes,’ Spence says. Callas performed her last opera in July of 1965 at just 41 years old.” After retirement, Callas lived out the rest of her life in isolation in Paris, numbing her mind with pills until her death by heart attack on September 16, 1977.

With Maria, Larraín captures this final, painful period in Callas’s life. She lives alone with her two dogs, whose devotion she attributes “99% to food”; her butler, Ferruccio (played by Pierfrancesco Favino, whose Best Supporting Actor nomination I’m riding for at dawn); and her housekeeper, Bruna (played by Alba Rohrwacher). A camera crew appears early in the film for an interview, and their sepia-soaked clapperboard shapes its three-act structure. Callas walks them through Paris, reminiscing on the moments exuberant, poignant, and outright painful that shaped her past. One of the movie’s most memorable scenes, for me, comes when Callas gets asked to shut the door on the past; she refuses, insisting that’s how the music gets in, fighting for her artistry until the bitter end.

Certain critics have decried the movie’s more theatrical elements, but, from my perspective, the kinds of sequences that feel sensationalized in Spencer (2021) land here. Each flare reflects the emotional quality of opera and, more importantly, Callas’s deteriorating sense of her surroundings. Her chosen cocktail of pills causes hallucinations, and various figures — from her sister, Yakinthi, to Onassis — float through the frame, their status as truth or illusion tenuous. Laffly continues: “While her end is inevitable in the film — Callas died in 1977 at the young age of 53 — you will be disarmed, even moved to tears, experiencing Larraín’s care for her in Maria, which is essentially a compassionate ghost story on the beloved things we lose, as they continue to deteriorate and slip through our fingers against our will.”

Where to Watch: ~a theater near you~, Netflix starting on 12.11

Jackie (2016, dir. Pablo Larraín) — Jackie (2016) traces the actions of Jackie Kennedy (played by Natalie Portman) in the week immediately following her husband’s assassination. As writer and critic Richard Lawson writes in a 2016 Vanity Fair piece: “Looping and dizzy, sad and intimate…Jackie is an odd, artful psychological study, one that blends stony seriousness with whispers of camp…Portman doesn’t do an exact imitation of Jackie’s birdy, breathy affectations, her curling downspeak at the end of sentences. But she does something that’s smartly evocative of it, while also delivering a compellingly modulated performance beyond all the mechanics of voice and bearing. In [Pablo] Larraín’s watchful aesthetic, Portman’s intensity works rather perfectly — together they create something transfixing, a film that washes over you as it loops and lingers.”

It opens with a journalist, an apparent avatar for Theodore H. White (played by Billy Crudup), arriving at the Kennedy compound in Hyannis Port, MA for a LIFE Magazine interview, Jackie’s first since JFK’s death. She immediately makes the terms clear: final oversight over and approval on anything that gets published. Chain-smoking on the porch, in the living room, Jackie recounts the events across and beyond the past week. Flashbacks abound, from the first televised tour of the White House (a program Portman replicates perfectly) to Jackie cradling her husband’s bloodied skull in her lap. The reporter condescends to and interrupts her, establishing one of the film’s primary themes: underestimation of Jackie, typically in the eyes of men.

In his 2016 RogerEbert.com review, Matt Zoller Seitz describes: “We see Jackie, often the lone woman in a room full of men, trying to assert herself and say what she wants and needs, only to be told (by White House staffers, military people, even her RFK) that it’s impossible — because of security or protocol or precedent or simply because the men just mysteriously know better than her — and she should give up.” Her tendency toward overspending, toward overdoing, gets mentioned often, first around her refurbishment of the White House, then JFK’s funeral. In one sequence, Jackie asks her driver if he’s heard of James Garfield or William McKinley, two other assassinated presidents, and gets met with a “no,” where Abraham Lincoln prompts immediate recognition. This moment leads her toward using Lincoln’s funeral as a blueprint for JFK’s service, an ostentatious affair inclusive of a horse-drawn caisson carrying his casket down Pennsylvania Avenue.

Jackie’s White House refurbishments get written off as frivolous, her funeral plans as dialed to 11 on a cloud of grief. But, in reality, both of these choices shape the legacy of her husband’s presidency, cultivate the notion of the Kennedys as enduring American royalty. JFK created the Peace Corps, established the basis for the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and successfully navigated the Cuban Missile Crisis. But those successes get remembered today through the prism of a myth, the notion of Camelot that Jackie coins in the LIFE Magazine interview chronicled by Larraín. In art and life alike, she explains: “There’ll be great Presidents again — and the Johnsons are wonderful, they’ve been wonderful to me — but there’ll never be another Camelot again.”

Where to Watch: Amazon Prime Video ($3.59)

Okay, that’s all for now! Stay tuned for the December newsletter tomorrow.

xo,

Najet