Last month, I read Welcome to the O.C.: The Oral History (2023), two fabulous picks from the Three Lives & Company team, and James Baldwin’s book-length film criticism essay, The Devil Finds Work (1976), before devouring Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955) in a matter of days. (~range~ lol)

Let’s get into it:

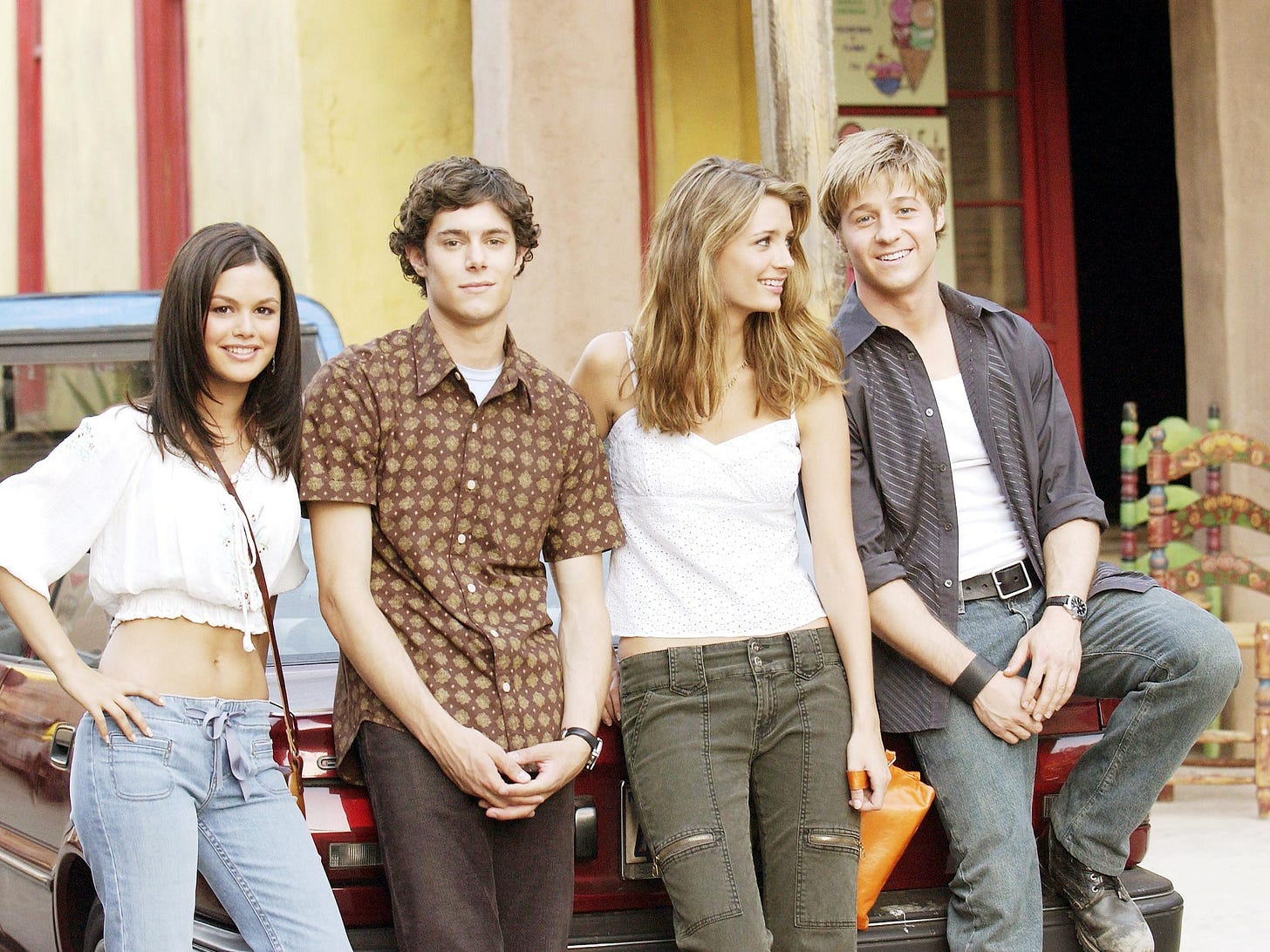

Welcome to the O.C.: The Oral History by Alan Sepinwall, Josh Schwartz, and Stephanie Savage (2023) — The thing about me is I love a teen drama, and The O.C. is no exception. Last year, showrunners Josh Schwartz and Stephanie Savage teamed up with Rolling Stone TV Critic Alan Sepinwall to develop a “comprehensive” (more on the air quotes in a minute) oral history of the early aughts hit. The book includes interviews with the cast, crew, and executives that developed and sustained the show over the course of four years, touching on the highs and lows of its turbulent run.

Sepinwall’s oral history functions, first and foremost, as a love letter. It unpacks how and why The O.C. helped shape its era’s cultural zeitgeist, while acknowledging the creative team’s key missteps (see: pretty much the entire third season). The showrunners’ involvement in the book’s production, however, means that certain narratives get pulled to the forefront, leaving a gaping, Mischa Barton-shaped hole at its center.

Throughout the interviews, Schwartz and especially Savage go to great lengths to position Barton, who famously played doomed heroine Marissa Cooper until her extremely public firing at the end of season three, as an outsider, as someone separate from the close bond shared by the rest of the cast. A handful of reasons for her social isolation emerge throughout the interviews, with the issue of her age getting referenced most frequently. (ICYMI: Barton was 17 during the filming of the pilot, while the rest of her costars had already entered their early 20s. Schwartz himself was only 26 when the show got green lit, leading to an especially cliquey atmosphere on set.) Barton offers her perspective to Sepinwall, but her quotes remain vague and somewhat perfunctory. For instance, when asked whether she wanted to leave the show at the end of season three, Barton explains: “I really don’t want to get into it at length. But there was a lot going on with the producers. I ultimately don’t get to make any decisions. That’s a fact. I had to do whatever my contract said I had to do. But I think that it was decided it was the best thing for the show in general.”

On the heels of the book’s August 2023 publication, Barton appeared on an episode of Alex Cooper’s Call Her Daddy. During it, Barton finally gives the full story. She explains that she briefly dated — and lost her virginity to — lead actor Benjamin McKenzie while filming the first stint of season one episodes. Feeling in over her head, she ended things. Her decision left McKenzie and the producers enraged, with her ex creating a hostile environment as a result. In a 2021 essay for Harper’s Bazaar, Barton writes, without naming names: “Did I ever feel pressured to have sex with someone? Well, after being pursued by older men in their thirties, I eventually did the deed. I feel a little guilty because I let it happen. I felt so much pressure to have sex, not just from him, but society in general. This was early on in those critical days and when I finally met someone new and wanted to remove myself from the situation, it created a toxic and manipulative environment. I felt controlled within an inch of my life.”

Compare these reflections to a quote from producer Stephanie Savage in Welcome to the O.C.: The Oral History. Savage, notably in her mid-30s during the show’s run, recalls: “There was one day when were shooting, and it was a really nice vibe on set. Everyone was sitting around laughing, telling stories. Mischa was sitting in her chair out by the pool house by herself with her back to us, reading…I just remember looking over there with a very immature feeling of, I guess she’s too cool for us now to sit around and laugh, versus a more mature feeling of, Maybe she feels left out. Maybe she doesn’t want to come over because she hasn’t been invited…Originally, we did a lot of things together, but as she got her different boyfriends, and was going to nightclubs with Paris and Nicole and being on Perez Hilton, she was more on her own island.”

Writer and historian Kelly Coyne reflects on Sepinwall’s oral history and Barton’s Call Her Daddy interview in an April Lit Hub piece, “Death and the Maiden: What Rewatching The O.C. Can Teach Us Now.” Coyne discusses society’s fixation with “the white starlet,” positioning Barton — and, by extension, her character — in a shared continuum with Britney Spears and Paris Hilton. She writes: “It doesn’t seem a coincidence that Barton appeared on Cooper’s podcast the same year that Hilton and Spears published memoirs accounting abuse by the people who were meant to protect them…and it doesn’t seem to be a coincidence that it was Cooper’s podcast where Barton agreed to share her story…Cooper, who unabashedly sells her image, is a hawk about making sure that she is the one — rather than figures like Barton’s ex-boyfriend, with his revenge porn; or the executives on The O.C., with the unconscious-Marissa motif; or Spears’s father, with her forced performances — who profits from it. These former starlets, after years of being raised and lowered on the media-industry flagpole for profit, are re-emerging to introduce themselves to Gen Zers. And it’s on Barton’s, Spears’s, and Hilton’s terms that this cohort is getting to know them.”

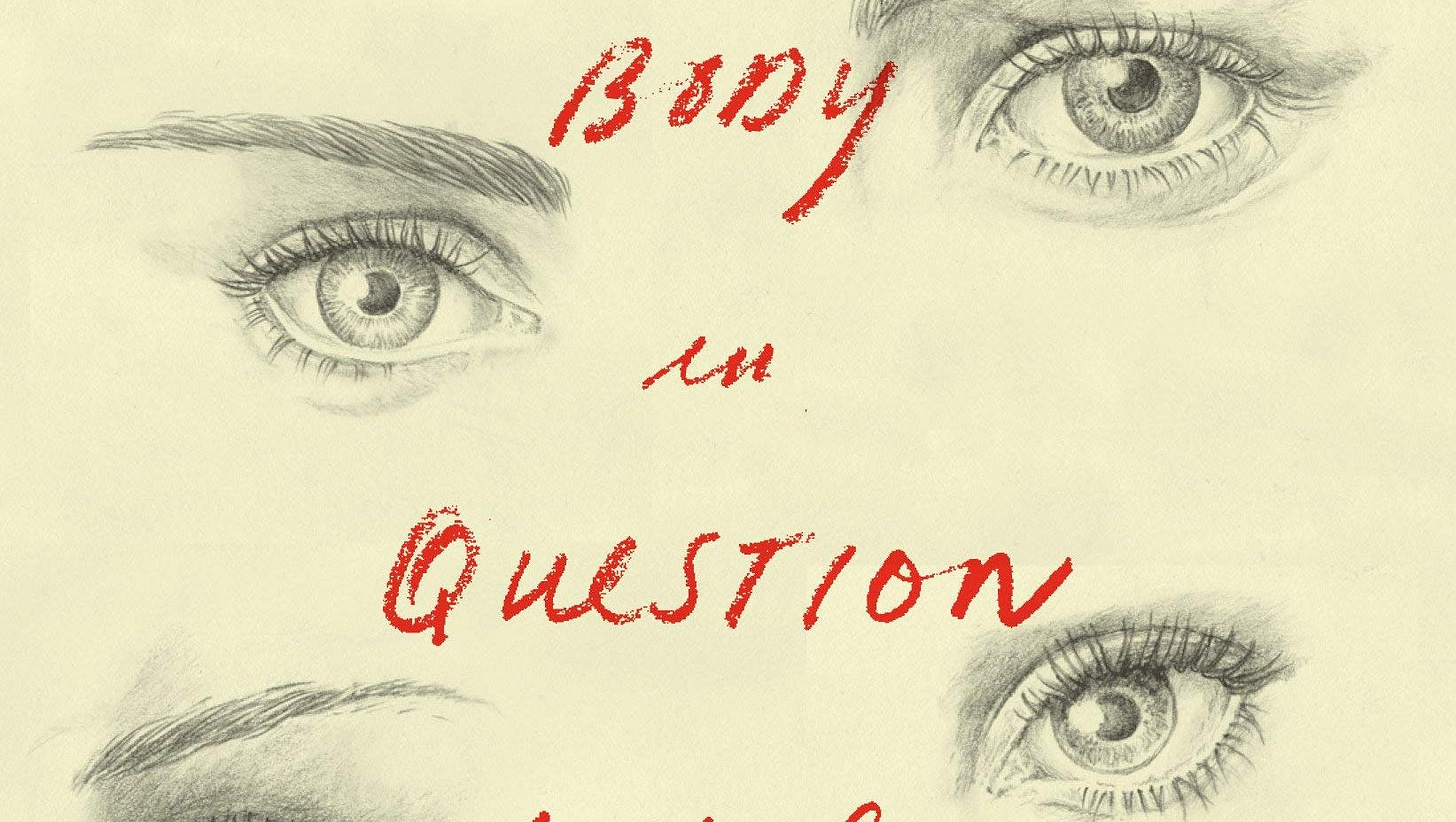

The Body in Question by Jill Ciment (2019) — What a perfect, propulsive summer read. From the author of Consent (2024), The Body in Question centers on a Florida murder trial, where one of two twin sisters has torched her family home and killed her baby brother in the process. Told in a close third-person perspective that stays tight to one of the jurors, a 52-year-old photographer, the novel examines the nebulous notion of truth at the hands of human error.

The first half of the book occurs during the tabloid-worthy trial itself, using juror numbers to reference the narrator — C-2 — and her peers, while the latter portion exposes their identities and the fallout of the verdict. Subjectivity drives the thrust of the tension as C-2 finds herself drawn into an affair with a fellow juror ten years her junior — F-17 —, an anatomy professor whose youth serves as a welcome counterbalance to the weight of her husband’s age (“An elderly stranger’s face fills the screen when it is C-2’s turn to Skype. Only when the frowning lips smile does she recognize her husband.”). With C-2 swept up in a cloud of lust, certain pieces of evidence diffuse into the air, coming back to haunt her during deliberation.

Ciment teases out a riddled plot that, in the hands of a lesser writer, could come across as soapy beyond belief. But her tight, scathing prose pierces the heart of each dynamic she examines. In her New York Times review, author Curtis Sittenfeld observes: “Ciment writes with a mordant intelligence and, refreshingly, doesn’t belabor topics that in someone else’s novel might take up many pages. That C-2 is ‘childless by choice’ is dispensed with in one sentence, and similar brevity is allotted to her previous extramarital ‘one-, two-, three-night stands.’ We learn that C-2 is neither beautiful nor distraught about her lack of beauty; for that matter, F-17 isn’t beautiful, either.” (At one point, C-2 “touches his [F-17’s] face again, reading the pitted skin like Braille.”)

Cultural markers situate the novel in time, tie it to a certain version of America. The jury votes on whether to see Magic Mike or Furious 7; summer 2015. The group dines out at chains ranging from Red Lobster to TGI Fridays to Cracker Barrel. The fictional Nic & Gladys, a restaurant whose owners have brokered a deal with the court to provide discounts in exchange for perpetual patronage, serves as the only independently operated alternative; Florida, indeed — far from the coasts. The jury stays at “the Econo Lodge across the interstate from Silver Springs…the hotel’s bright orange sign with its whirlpool design and twinkling star…reminiscent of a Tide detergent box.” Specificity and universality press up against one another, as Ciment riddles the novel with regional details that connote a particular American experience.

The Body in Question also serves as a fascinating meditation on age difference relationships, on the inevitable toll of time. C-2 reflects on her 86-year-old husband’s physical decline, on how his virility increasingly becomes something to grasp at rather than an unspoken truth (“They still have sex, but nothing she would have called, at sixteen, ‘all the way.’ He doesn’t so much possess her as haunt her.”). This aspect has obvious biographical ties to Ciment’s experience partnering with, then caring for, a man nearly thirty years her senior, the basis of her companion memoirs, Half a Life (1996) and Consent, which now have moved onto my to-read list.

Very Cold People by Sarah Manguso (2022) — A haunting meditation on girlhood, Very Cold People enlivens Waitsfield, Massachusetts from the first-person perspective of Ruthie, a Jewish Italian girlie trying to make sense of the frozen town that raised her (“My own girlhood felt like something from 1650 even when it was happening. The little parties, kindnesses done by friends, the light as I walked home from school. Pine needles. I spent those days feeling half-there, not quite committed to that life.”). Told in brief vignettes by an adult Ruthie, this rhythmic read looks back on the web of friendships, of local myths, of family scars that came to comprise her childhood. Manguso implements a kaleidoscopic lens at points, hindsight afforded by Ruthie’s age that slowly reveals the dismal fates of her peers. Abuse bubbles beneath Manguso’s nostalgic, pared-back prose, becoming overt only toward the novel’s end.

To correctly convey the sensory experience stirred by this novel, an ambient dissection of race, class, and gender in small-town New England, I would echo the sentiments expressed by critic Johanna Thomas-Corr in her review for The Guardian. She writes: “When I finished Very Cold People, I felt my whole body unclench. In the process of reading this creepy coming-of-age tale, I seemed to have trapped a nerve in my shoulder — it’s that tense. It’s a novel in which nothing very much happens for about 100 pages but small objects — Barbie dolls, Girl Scout sashes, bubble gum, nail polish, a knitted scarf — assume vast significance, and small kindnesses feel overwhelming. When a friend tips candy into the hand of the narrator, Ruthie, she says: ‘I couldn’t believe how much she was giving me. Just giving it to me, when she could have eaten it herself.’ Any act of generosity feels too good to be true…It unfolds like a much darker version of Roald Dahl’s Matilda — only told at a glacial speed, with no Miss Honey coming to the rescue.”

The Devil Finds Work by James Baldwin (1976) — This book-length essay from one of the twentieth century’s most prolific writers, a Leo legend who would have turned 100 this week, examines representations of the Black experience in Western cinema, unpacks how American delusion seeps into the kind of media we consume. Divided into three sections, The Devil Finds Work opens with a memoir-like look back at James Balwin’s childhood, at how a schoolteacher and mentor first brought him into the bewitching world of film. He then analyzes mid-century representations of race relations, with a special focus on Sidney Poitier, before delving into his doomed adaptation of The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965) for the big screen.

Baldwin’s cultural criticism spans a broad swath of films, ranging from The Birth of a Nation (1915) to Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? (1967) to The Exorcist (1973). His discussion of In the Heat of the Night (1967) strikes me as somewhat reminiscent of the discourse around Green Book (2018) that dominated Oscar conversations in early 2019. Regarding the acclaimed Poitier film, Baldwin writes: “Our situation would be far more coherent if it were possible to categorize, or dismiss, In the Heat of the Night so painlessly. No: the film helplessly conveys — without confronting — the anguish of people trapped in a legend,” a statement that might just as easily apply to the controversial 2019 Best Picture winner. Baldwin discusses what gets lost in translation in the shift from initial script to final film, drawing on his own experience with The Autobiography of Malcolm X to underscore how narratives get strategically “translated” to appease studios and, by extension, maintain a myth for white audiences.

Of the films discussed, I have only seen Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? (1967) and found myself wishing I had a stronger grasp on the body of work Baldwin analyzes. While you can approach this book without having seen any, I would recommend watching at least one, ideally starring Poitier, before picking up this essay.

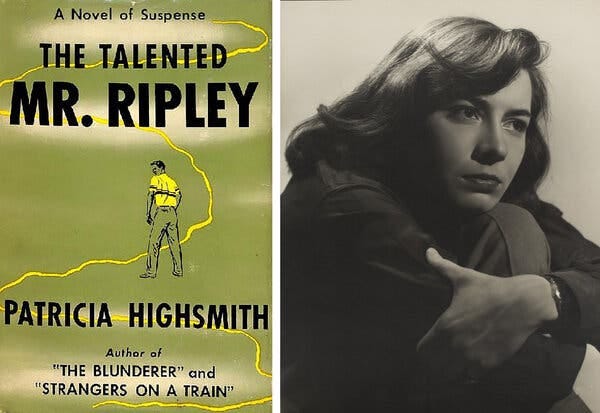

The Talented Mr. Ripley by Patricia Highsmith (1955) — I devoured this novel in a matter of days despite my deep familiarity with the plot, having seen both Alain Delon’s and Matt Damon’s interpretations of the character in Purple Noon (1962) and The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999), respectively. (I only watched half an episode of the new Ripley Netflix show starring Andrew Scott because I famously Can’t Finish Television Programs.)

Highsmith’s novel adopts a close third-person point of view, inhabiting the paranoid and particular mind of Tom Ripley (“Tom had imagined horrible things during the boat trip: Marge beating him to Palermo by plane, Marge leaving a message for him at the Hotel Palma that she would arrive on the next boat. He had even looked for Marge on the boat when he got aboard in Naples”). It begins with a jolt, as Highsmith writes: “Tom glanced behind him and saw the man coming out of the Green Cage, heading his way. Tom walked faster. There was no doubt the man was after him. Tom had noticed him five minutes ago, eyeing him carefully from a table, as if he weren’t quite sure, but almost. He had looked sure enough for Tom to down his drink in a hurry, pay and get out.” These opening lines create a kind of kinship between Tom and the reader, mimic the feeling of a hot pursuit experienced in parallel.

“The man coming out of the Green Cage” emerges as shipping magnate Herbert Greenleaf. To bring his son, Dickie, back to the United States, he recruits Tom to travel to Italy on his dime in a desperate attempt at persuasion. Upon arrival, Tom immediately gets off task (“Another week went by, of ideally pleasant weather, ideally lazy days in which Tom’s greatest physical exertion was climbing the stone steps from the beach every afternoon and his greatest mental effort trying to chat in Italian with Fausto, the twenty-three-year-old Italian boy whom Dickie had found in the village and had engaged to come three times a week to give Tom Italian lessons”). He befriends Dickie and his pseudo-girlfriend, Marge, living out an idyllic seaside life on Mongibello — until jealousy and rage come to consume him.

Highsmith maintains the sensation spurred in her opening paragraph, one that viewers of Netflix’s You will find familiar, over the course of the ensuing 250+ pages (“His [Tom’s] answers to their questions were ready in his head. It was like waiting interminably for a show to begin, for a curtain to rise.”). Her careful use of a close third-person perspective establishes a sense of unwanted emotional intimacy that defies logical thought; she leaves the reader rooting for the novel’s sociopathic titular character without real reason, a high-wire act that underscores the unnerving subjectivity of morality.

Stay tuned for the August newsletter tomorrow!

xo,

Najet

Ruby and I need to revisit this recommendation