So, April is always kind of gloomy, and the vibes frequently feel a little off, at least to me. Rather than ignore that energy, I’ve decided to lean into it for this month’s newsletter.

Let’s get into it:

April Book Selections

Since April showers allegedly bring May flowers, I’m bringing you a list of book selections with rainy vibes, either literally, atmospherically, or emotionally.

Recommendations for the month ahead include:

We Run the Tides by Vendela Vida (2021) — This moody, misty novel embodies the notion of liminality, of existing in an in-between space, by zeroing in on a place and a person on the verge of what the back cover correctly characterizes as “radical transformation.”

We Run the Tides opens in 1980s San Francisco, a period bookended and muted by the reigns of Haight-Ashbury hippies and Steve Jobs-worshipping SAAS founders, and traces the coming-of-age journey of its eighth grade narrator, Eulabee. At the story’s start, Eulabee and her best friend, Maria Fabiola, dominate the oceanside neighborhood of Sea Cliff (“We are thirteen, almost fourteen, and these streets of Sea Cliff are ours. We walk these streets to our school perched high over the Pacific and we run these streets to the beach, which are cold, windswept, and full of fishermen and freaks.”). But the fault lines in their friendship begin to emerge, leading to an abrupt falling out, then Maria Fabiola’s disappearance, cracking open the contours of Eulabee’s reality.

This novel is extremely vibey. If you’ve been following this Substack a while, you’ll recall my piece from last summer, “On Vibes in Film and Fiction”: “Fiction becomes a vibe rather than merely stylized when its narrative voice — regardless of tense — embeds interiority with the outside world. In her debut, Vladimir, Julia May Jonas writes: ‘Like every year, the cold came more quickly than expected. The day after the pool guy came there was a sudden frost, and the dirt froze into a spongelike formation that crunched when stepped on. That morning I pulled out my white woolen cardigan that I bought from the Salvation Army in my twenties and layered it over a long flannel nightgown with bulky fisherman’s socks and my indoor sandals.’ This passage situates the unnamed narrator in an external environment marked by sudden cold, frozen dirt, inescapable chill. It reveals age and leaves the reader to discern what the choice to pair a cardigan with a flannel nightgown, ‘bulky fisherman’s socks,’ and indoor – not outdoor – sandals says about her. In the span of three sentences, the reader learns something about this woman’s inner and outer life.”

Vendela Vida, like Vladimir author Julia May Jonas, twists her narrator’s inner life and outer environment into a double helix. Eulabee narrates: “We take take the boys from Sea View to the beach and under their gaze we see how agile we are. We can feel our power as we race on all fours over to the cliffs — we know their crevices and footholds, their smooth inclines and their rugged patches. If there were an Olympic category for climbing these cliffs, we would enter it; we scale them as though we are in training. After an afternoon at the beach, the pads of our fingers are rough, and our palms smell of damp rock, and the boys are dazzled.” This particular passage reveals how Sea Cliff cultivates Eulabee’s sense of self; its topography sharpens and showcases her agility before boys, alongside her friends.

As the narrative progresses, Eulabee moves toward the brink of change alongside her neighborhood and, ultimately, her city. By toggling between first-person plural and singular, Vida underscores Eulabee’s concurrent isolation and self-actualization. In her review of We Run the Tides for The New York Times, Molly Fischer writes: “Is there a better way to come of age than in the first-person plural? Teenage stories take well to a ‘we.’ Think of Jeffrey Eugenides’s The Virgin Suicides, narrated in an amorphous chorus of male adolescence, all those neighborhood boys speaking in a single voice of shared desire. The teenage ‘we’ bespeaks an anxiety to belong, a craving for group identity that marks others as outsiders — but also a willingness to issue sweeping judgments and proclamations (“Everyone is going, Mom!”). Maybe no one belongs with so much certainty ever again…‘We’ is where the heroine begins in We Run the Tides…and the book follows her as she emerges from this first-person-plural embrace.”

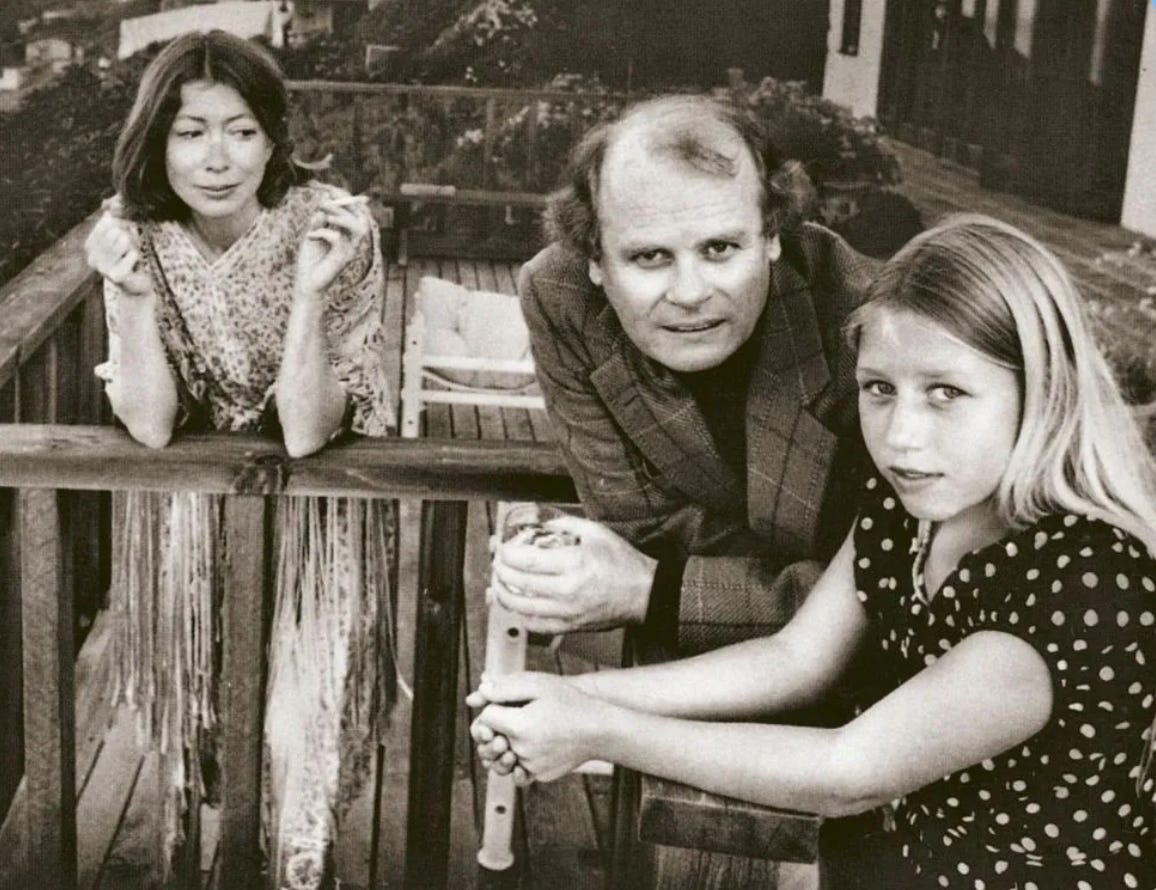

Blue Nights by Joan Didion (2011) — The Year of Magical Thinking (2005) has arguably cemented itself as the definitive grief book over the past two decades. But Joan Didion’s nonfiction follow-up from 2011, Blue Nights, deserves the same level of attention, if not more, from my perspective.

Didion married fellow writer John Gregory Dunne in 1964 and, in 1966, adopted a daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne. In 2003, Dunne died from a heart attack in their New York City apartment. Didion wrote The Year of Magical Thinking as she processed her grief. In 2005, Quintana died of pneumonia. Didion wrote Blue Nights, which, per NPR, “piece[s] together literary snapshots, and retrieved memories about her daughter's life and death…Her prose, in the past, just gleamed — terse, elegant, understated and piercing. The new book is what's left, after loss.”

Blue Nights elicits the sensation of Didion grasping at, recording, the shards of memories slipping through her fingers. She resurrects the visual of Quintana on her wedding day, draped in a lei at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. Didion writes: “There were cucumber and watercress sandwiches, a peach-colored cake from Payard, pink champagne. Her choices, all. Sentimental choices, things she remembered. I remember them too…On the day of the wedding she got all her sentimental choices except one: she had wanted the little girls to go barefoot in the cathedral (memory of Malibu, she was always barefoot in Malibu, she always had splinters from the redwood deck, splinters from the deck and tar from the beach and iodine for the scratches from the nails in the stairs in between) but the little girls had new shoes for the occasion and wanted to wear them.” By teasing out the hidden significance of the seemingly small, of “sentimental choices,” Didion makes a poignant case for the power of remembrance.

Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante (2002) — A true Novel to Read in April, Days of Abandonment opens with its 38-year-old narrator, Olga, explaining: “One April afternoon, right after lunch, my husband announced that he wanted to leave me. He did it while we were clearing the table; the children were quarreling as usual in the next room, the dog was dreaming, growling beside the radiator…He talked for a long time about our fifteen years of marriage, about the children, and admitted that he had nothing to reproach us with, neither them nor me.” The ensuing 200ish pages trace the disintegration of the relationship through the prism of Olga’s grief, anger, and confusion, culminating in a rhythmic novel awash in mood.

Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency by Olivia Laing (2020) — This collection from British writer Olivia Laing makes a case for the value of art in turbulent times, in moments when its impact becomes questionable. It includes conversations with and about different artists; per the back cover, Laing “profiles Jean-Michel Basquiat and Georgia O’Keeffe, reads Maggie Nelson and Sally Rooney, writes love letters to David Bowie and Freddie Mercury, and explores loneliness and technology, women and alcohol, sex and the body.”

The various chapters highlight the sociological, cultural, and political importance of artists over time, underscoring the transcendent impact of their work. Laing asserts: “Part of why I think it’s absurd to say that art can’t change anything is that I don’t think there’s a political realm that’s truly separate from the cultural realm or the emotional realm or the social realm. Which is what I was trying to get at with Crudo, the immense entanglement of everything.” That “immense entanglement” distinguishes Funny Weather, a book defined by how it knits threads of culture together to illustrate art’s ability to refract reality through its distance.

Upcoming Content to Consume

Strangers on a Train (1951) at The Paris Theater (Date: 4.2) — What a film. I had the pleasure of seeing Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1951), based on The Talented Mr. Ripley author Patricia Highsmith’s eponymous 1950 novel, at Film Forum last year, and I had to remind myself to breathe for the final hour, which features arguably the most intense tennis match in cinematic history (and I say this as a non-sports girlie).

As its title suggests, the film opens with a chance encounter between two strangers, tennis pro Guy Haines (played by Farley Granger) and peppy psychopath Bruno Antony (played by Robert Walker), on a train. Bruno strikes up a conversation with Guy, who hopes to divorce his wife, Miriam (played by Kasey Rogers), and marry Anne Morton (played by Ruth Roman), the daughter of a U.S. Senator. Bearing his own axe to grind with his father, Bruno “jokingly” suggests the pair swap murders (“Your wife. My father. Criss cross.”), propelling the plot into a series of dark, twisty turns.

In the immortal words of my girl Pauline Kael: “Hitchcock’s bizarre, malicious comedy, in which the late Robert Walker brought sportive originality to the role of the chilling wit, dear degenerate Bruno; it’s intensely enjoyable — in some ways the best of Hitchcock’s American films…It isn’t often that people think about a performance in a Hitchcock movie; usually what we recall are bits of ‘business’ — the stump finger in The 39 Steps, the windmill turning the wrong way in Foreign Correspondent, etc. But Walker’s performance is what gives this movie much of its character and its peculiar charm.”

Catch this one at The Paris Theater this week or stream it at home!

The Paris Theater’s Academy Museum Branch Selects Series (Opening Date: 4.3) — Starting this week, The Paris Theater will partner with The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in Los Angeles to co-present a selection of 18 films, one chosen by each branch of the Academy. The series will run through June, with films screening Wednesdays at 7:00 PM and Sundays at 12:00 PM.

I’ll call out compelling picks here each month through June. For April, highlights include Grey Gardens (1975), selected by the Documentary Branch, and King Kong (1933), chosen by the Sound Branch. King Kong has sat on my to-watch list for years thanks to its ranking on the AFI 100, and I streamed Grey Gardens with my mom (lol) last Fourth of July weekend.

Grey Gardens depicts the everyday lives of a mother and daughter, both named Edith Bouvier Beale, nicknamed Big Edie and Little Edie, respectively. The reclusive mother-daughter duo, aunt and first cousin to Jackie Kennedy, first reached the public radar in the early 1970s, when their state of squalor led to dual features in The National Enquirer and, more reputably, New York Magazine. In her 1972 piece for New York Magazine, Gail Sheehy writes: “This is a tale of wealth and rebellion in one American Gothic family. It begins and ends at the juncture of Lily Pond Lane — the new Gold Coast — and West End Road, which is a dead end. There, in total seclusion, live two women, twelve cats, and occasional raccoons who drop through the roof of a house like no other in East Hampton.”

Per The White Review: “In 1972, [Lee] Radziwill set out to shoot her own documentary — which would be titled Reminisces of Old East Hampton — about her family, including her aunt and cousin, the Beales, who by this time had been living together for over 20 years. The photographer Peter Beard, a friend of Radziwill’s, joined the project. He introduced Radziwill to the Maysles brothers, whom she hired for the shoot. Several reels were shot, but the project was eventually shelved, and the footage lost until very recently. But the Maysles had found subjects in the Beales, and returned in 1974 — without, it’s rumored, Radziwill’s blessing — to shoot Grey Gardens.” The result? “A ghost story, a Southern Gothic drama set 600 miles from the south (‘Don’t you love the overgrown Louisiana Bayou look!’, in Little Edie’s words). In another, it’s a piece of searing social commentary, an acute observation of broken-down bourgeois existence, a mutation of high society living.”

You can check out the full line-up for Academy Museum Branch Selects here.

Film Forum’s Delon Series (Dates: 4.12-4.18) — An entire series dedicated to France’s sexiest actor, Alain Delon. We simply love to see it.

I recommend seeing Purple Noon (1960), which I discussed in the first-ever newsletter after seeing it at The New Bev (“Come for shirtless Alain Delon on a boat, stay for shirtless Alain Delon on a boat.”), La Piscine (1969), and Mr. Klein (1976).

Albertine: Liberty Equality Fashion, The Women Who Styled The French Revolution (Date: 4.16) — ICYMI: I randomly have an Art History degree from Barnard, where I studied under Professor Anne Higonnet. While my thesis focused on Jackson Pollock and theatre theorist Antonin Artaud, an area outside her purview, I took a number of Higonnet’s classes over the years, and she served as my academic advisor.

On April 16th, Higonnet will join Caroline Weber, “a Professor of French specialized in the literature and history of the 17th- and 18th-century royal court, the Enlightenment, and the French Revolution at Barnard,” at Albertine to discuss Higonnet’s newly published book, Liberty Equality Fashion, The Women Who Styled The French Revolution.

Per Albertine: “Higonnet and Weber will delve into the lives of Joséphine Bonaparte, future Empress of France; Térézia Tallien, who was considered, at the time, the most beautiful woman in Europe; and Juliette Récamier, muse of intellectuals, who had nothing left to lose. Our speakers will analyze how, after surviving incarceration and forced incestuous marriage during the worst violence of the French Revolution of 1789, these three women, together, led a fashion revolution and turned themselves into international style celebrities.”

For those of you unfamiliar, “tucked inside the historic Payne Whitney mansion, Albertine is the only bookshop in New York devoted solely to books in French and English with more than 14,000 contemporary and classic titles from 30 French-speaking countries. As an integral part of the Cultural Services of the French Embassy, the Albertine bookshop brings to life the French government’s commitment to French-American intellectual exchange.”

This event, an English-language one, will occur at 6:00 PM. You can RSVP here.

Cake Zine Turns 2: Reading and Garden Party (Date: 4.11) — Cake Zine is “an independent print magazine exploring history, pop culture, literature, and art through sweets.” Each issue has a unique theme — from Wicked Cake to Humble Pie to Tough Cookie — and welcomes formats from personal essays to poetry to short fiction, with authors Sanaë Lemoine [The Margot Affair (2020)] and Catherine Lacey [The Answers (2017), Pew (2020), Biography of X (2023)] among its contributors.

To mark the magazine’s second anniversary, the Cake Zine editorial staff will host an evening of readings from its archives at The Invisible Dog Art Center in Cobble Hill on April 11th. Doors will open at 7:00 PM, with readings beginning at 7:30 PM, followed by a garden party until 10:00 PM. Discounted magazines and treats from all of the issues will be available for sale.

Tickets cost $10.89 and include one drink of your choice, with all proceeds going toward Anera, a nonprofit dedicated to providing food, water, and healthcare in Palestine.

Apocalypse Now: Final Cut (1979) at Metrograph (Date: 4.13) — I have not seen this film, but I’m fascinated by it after getting down my Francis Ford Coppola 1977 rabbit hole back in January. Based on Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1899), Apocalypse Now reinvents the novella for the Vietnam War era. Thanks to its famously doomed production process — and Coppola’s own mania —, “Apocalypse Now spent nearly two years in post-production and the film's budget capped off at $30 million,” with my chaotic king “having shot over 1,000,000 feet of film,” per Collider.

In 2001, Coppola released a new version, Apocalypse Now: Redux, with 49 additional minutes of footage that failed to make it into the original film, followed by Apocalypse Now: Final Cut, which debuted at the 2019 Tribeca Film Festival to mark the movie’s 40th anniversary. Per Wikipedia: “This new version [Final Cut] is Coppola's preferred version of the film and has a runtime of three hours and three minutes, with Coppola having cut 20 minutes of the added material from Redux.”

Metrograph’s Filmcraft: Frederick Elmes Series (Dates: 4.13-4.27) — This upcoming series will focus on the work of cinematographer Frederick Elmes. His career spans over four decades, and Metrograph’s line-up will bring together “Elmes’ most ravishing works…with two of his chosen inspirations, Cries and Whispers (1972) and Tess (1979).” My favorites in this series include David Lynch collaborations Blue Velvet (1986) and Wild at Heart (1990).

Per Metrograph, Elmes describes his style as follows: “I don’t really have a filmmaking philosophy I live by, but in my favorite scene in Wild At Heart, Lula and Sailor, broke, on the run, and with only bad news on the radio, leave their car on the side of the road, dance wildly and embrace, silhouetted by the setting sun. In that fleeting moment, we relinquished control, relied on instinct, and captured the ineffable.”

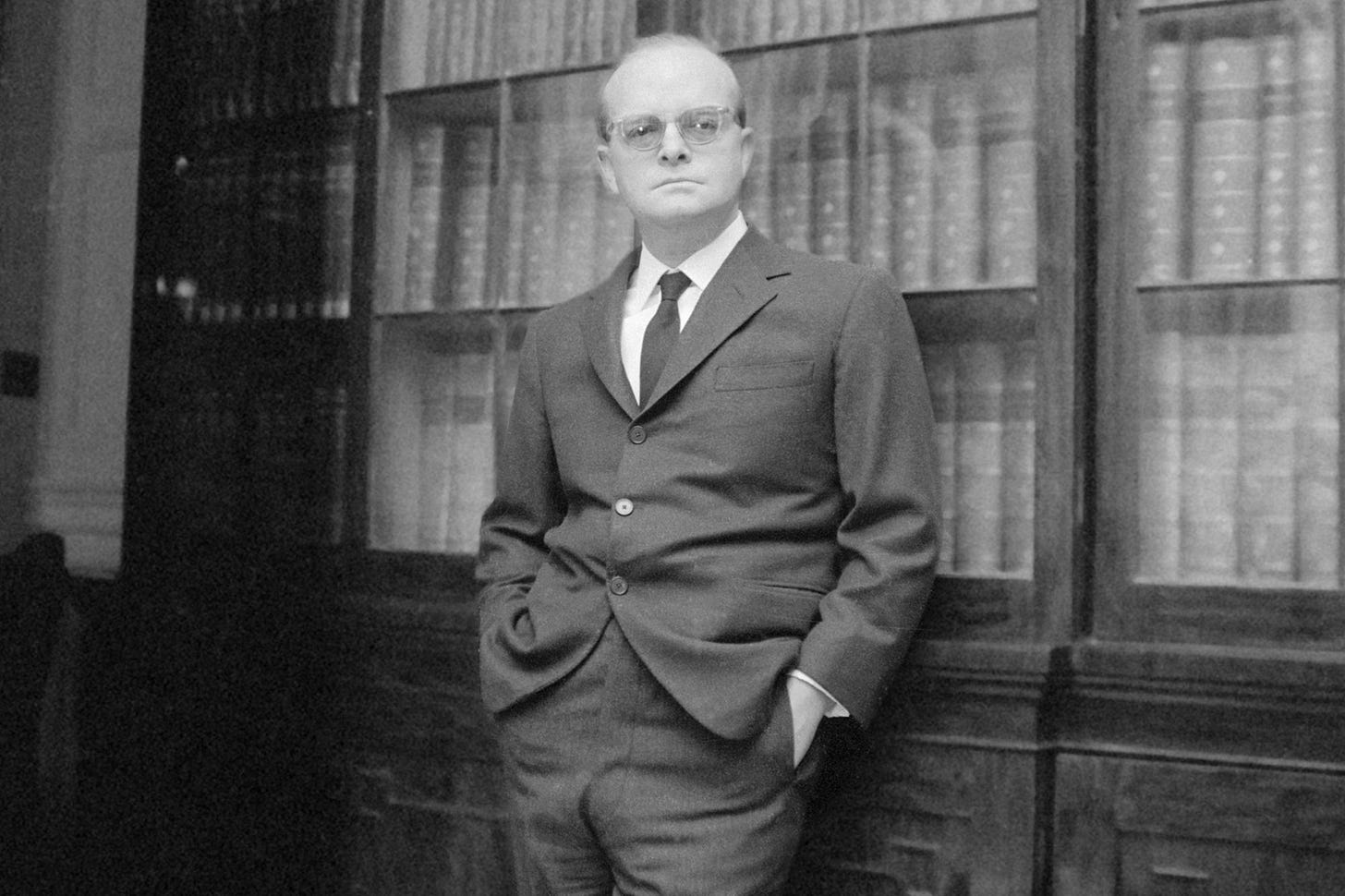

The Center for Fiction: Celebrating Truman Capote During His Centennial Year with Elizabeth Howard (Dates: 4.16 and 4.23) — Truman Capote is inarguably having a moment right now on the heels of Ryan Murphy’s Feud: Capote vs. The Swans (2024). This year would have marked the author’s 100th birthday, so, to celebrate the moment, The Center for Fiction has announced an upcoming two-part reading series focused on three of his works.

Per The Center for Fiction: “Truman Capote was born on September 24, 1924 — 100 years ago. He died in 1984, just as he was turning 60. He twice won the O. Henry Memorial Short Story Prize and was a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters. ‘Miriam’ was his first short story, published in 1945 in Harpers Bazaar and attracting much attention. ‘A Tree of Night’ was published in a collection of stories in 1949. In 1951 his novel, The Grass Harp, was published to much acclaim. Although it was described as being ‘too sentimental,’ most agree it was Capote’s favorite personal work.”

The reading group will meet twice on Tuesdays, April 16th and April 23rd. The first evening’s discussion will center on “Miriam” and “A Tree of Night,” while the second will focus on The Grass Harp with a girl dinner of Prosecco and birthday cake to follow.

New Beverly Cinema: In a Lonely Place (1950) and The Big Heat (1953) (Dates: 4.25-4.26) — A Gloria Grahame double feature for my LA subscribers! One of Old Hollywood’s most underrated actresses. I have not seen The Big Heat, but In a Lonely Place is one of my favorites.

Loosely based on the eponymous novel by Dorothy B. Hughes, In a Lonely Place, per The New Bev, centers on Dix Steele (played by Humphrey Bogart) “a down-on-his-luck studio scribe who reluctantly agrees to adapt a trashy bestseller to the silver screen. Rather than read the book himself, Steele convinces a star-struck hatcheck girl, Mildred Atkinson, to accompany him home and tell him the story in her own words. Later that night, Mildred is found murdered and Steele, who has a history of violent behavior, becomes the prime suspect.” When a romance brews between Dix and his neighbor Laurel Gray (played by Grahame), questions of trust and truth begin to bubble.

Miscellaneous Musings

Bret Easton Ellis on Mental Health and Addiction — ICYMI: my problematic parasocial bestie Bret’s longtime boyfriend, Todd Michael Schultz, in the midst of a psychotic break, got arrested for trespassing into a neighbor’s apartment in their West Hollywood building last month.

Bret and Todd have been together for the better part of 14 years, and Todd has struggled with mental health and addiction issues for the duration of their relationship. On the heels of this highly publicized moment (see: NYT article with the headline “Boyfriend of Bret Easton Ellis Arrested in Hollywood”), Bret wrote and published an Instagram statement about the far-reaching impact of mental health and addiction issues.

Unable to concentrate on the usual film criticism and guest interviews, Bret took that conversation to The Bret Easton Ellis Podcast, where he answered listener questions about those themes through and beyond the prism of his relationship. The set of episodes (linked here and here) serves as a candid, poignant meditation on the thin line between care and complicity.

“Repetition” by Vigdis Hjorth — Babe, wake up, new Vigdis Hjorth in just dropped in Granta! You might recall that I raved about Hjorth’s propulsive novel, Will and Testament, back in November, praising her use of repetition, her ability to tease out her narrator’s trauma through form. This notion unspools on a smaller scale in her latest short story.

“Repetition” centers on an unnamed narrator spending a week in a cabin — reading, sleeping, dreaming. She travels to see the University of Oslo Symphony Orchestra’s annual carol concert, having promised a friend to attend. Upon arrival, the narrator becomes fixated on a family seated near her, observes how “we are tied to our family from our first breath to our last.”

She explains: “I had just read that repetition is the reality and the seriousness of life, that repetition is the daily bread of everyday life, its blessing fills you up, and seeing as I had attended the orchestra’s carol concert for three years in a row, I hoped that it would indeed prove to be a blessing…soon the world would be dazzling, white and shimmering, and anything sharp and pointy would be smoothed over. It was something that happened every year at this time, it recurred and repetition is the reality and seriousness of life.” This concept of repetition as a salve for the “sharp and pointy” explains the impulse to relive the same moments again and again in an attempt to smooth them over, distilling a macro theme in Hjorth’s work on a micro scale.

Which Paris Review Cover Are You? — For the first time in its 71-year history, The Paris Review has printed two covers, original pastels from Swiss artist Nicolas Nicolas Party, to usher in its spring issue. Pretend BuzzFeed didn’t fold and take a quiz with questions inspired by the issue’s content to find out which one of the two best fits your ~vibe~ here.

Supplemental Reading

As always, don’t forget to use archive.ph if you can’t access these pieces or any of the ones throughout my Substack!

Vanity Fair: Crazy Love: Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton’s Epic Romance

Air Mail: A Tale of Two Royal Households

Thinking About Getting Into: On Being an Appreciator of the Arts

London Review of Books: Is it even good? Brandon Taylor reads Zola

New York Daily News: Richard Burton’s diaries reveal the passion and pain of his love story with Elizabeth Taylor

Cocktail of the Month

Having entered my Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor hyperfixation era (basique, I know // more on that in the March Book Review), I’ve chosen Taylor’s favorite cocktail, first tasted at Puerto Vallarta’s Casa Kimberly Hotel, as this month’s recipe.

Rub the rim of a martini glass with a quarter of an orange. Then, sprinkle one teaspoon of cocoa powder over a saucer, and dip the rim of the glass in the cocoa powder to coat it. Set your glass to the side.

Next, pour one ounce of vodka, a half ounce of crème de cacao liqueur, and a half ounce of chocolate syrup into a cocktail shaker with ice.

Shake well, strain, and pour into the prepared glass.

That’s all for now! I also saw The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism at The Met this weekend, which was stunning, but we’re going to talk about that exhibition in the May newsletter.

In the meantime, stay tuned for the March Book Review later this week!

xo,

Najet