Hello, and happy September! The vibes are back to school with a Ripley-coded dash of “can we plz hold onto summer for another minute.”

Let’s get into it:

September Book Selections

Okay, so, we’re ~learning~ this month and also reading Bret Easton Ellis’s Bennington novel.

Recommendations for the month ahead include:

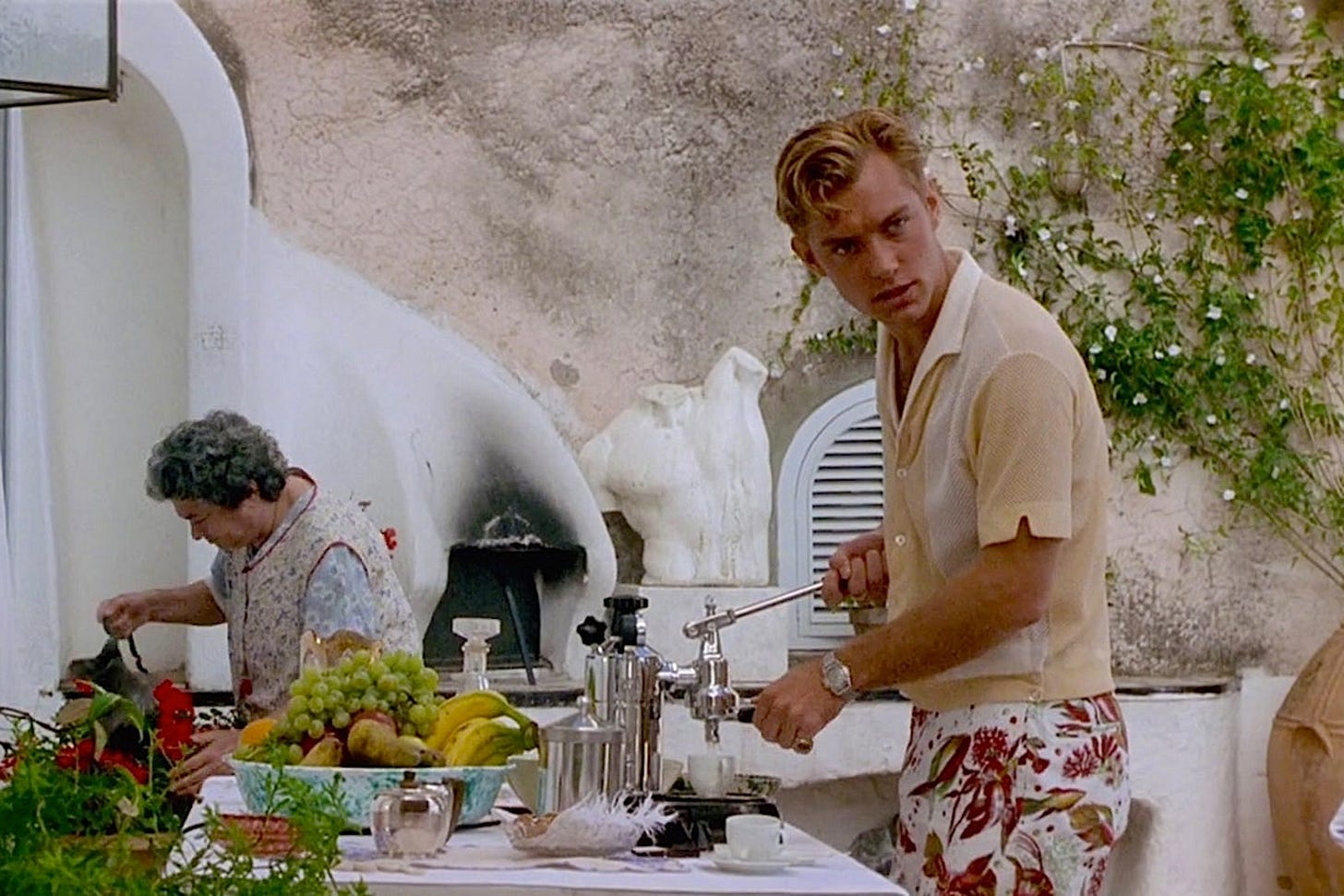

The Talented Mr. Ripley by Patricia Highsmith (1955) — ICMYI: I am deeply in my Ripley era after reading the novel last month, then watching the TV show (yes, I actually finished it, more on that in a minute) and starting Highsmith’s sequels (as discussed in the August Book Review). This novel takes place largely across fall and winter, but maintains Italian summer vibes along the way, making it the perfect September read.

As you probably know (or maybe not given the number of girlies captioning their Positano photos “following in Dickie Greenleaf’s footsteps” without consideration for the character’s fate, the Euro Summer version of “My Best Friend’s Wedding”), the novel centers on Tom Ripley, a sketchy American who takes a break from concocting insurance scams to help shipping magnate Herbert Greenleaf persuade his expat son, Dickie, to return home from Italy. Homoerotic subtext emerges, and Dickie meets an untimely end, leaving an opening for Tom to assume his identity. As I wrote in the July Book Review:

Highsmith’s novel adopts a close third-person point of view, inhabiting the paranoid and particular mind of Tom Ripley (“Tom had imagined horrible things during the boat trip: Marge beating him to Palermo by plane, Marge leaving a message for him at the Hotel Palma that she would arrive on the next boat. He had even looked for Marge on the boat when he got aboard in Naples”). It begins with a jolt, as Highsmith writes: “Tom glanced behind him and saw the man coming out of the Green Cage, heading his way. Tom walked faster. There was no doubt the man was after him. Tom had noticed him five minutes ago, eyeing him carefully from a table, as if he weren’t quite sure, but almost. He had looked sure enough for Tom to down his drink in a hurry, pay and get out.” These opening lines create a kind of kinship between Tom and the reader, mimic the feeling of a hot pursuit experienced in parallel.

Highsmith maintains the sensation spurred in her opening paragraph, one that viewers of Netflix’s You will find familiar, over the course of the ensuing 250+ pages (“His [Tom’s] answers to their questions were ready in his head. It was like waiting interminably for a show to begin, for a curtain to rise.”). Her careful use of a close third-person perspective establishes a sense of unwanted emotional intimacy that defies logical thought; she leaves the reader rooting for the novel’s sociopathic titular character without real reason, a high-wire act that underscores the unnerving subjectivity of morality.

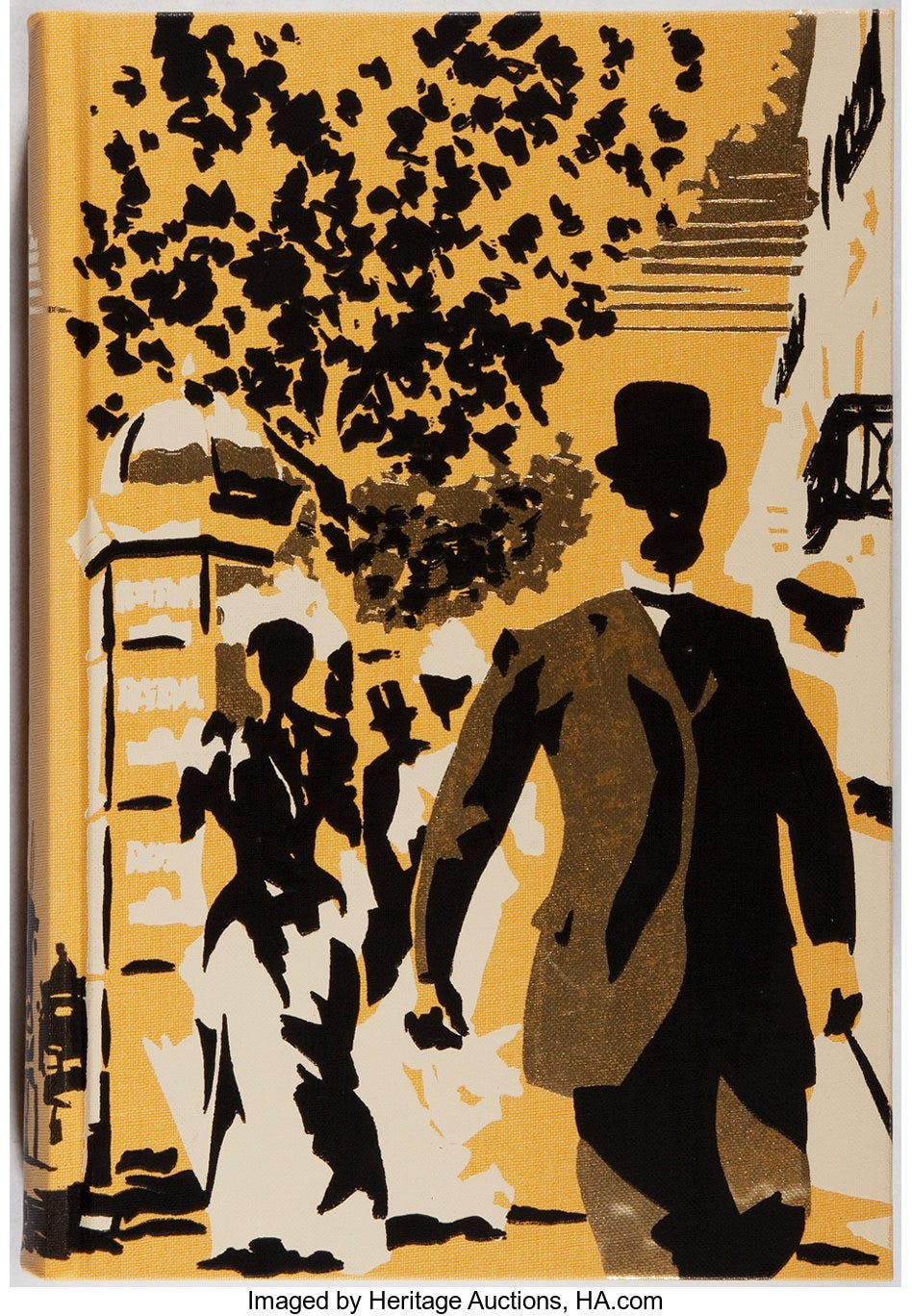

The Ambassadors by Henry James (1903) — Highsmith frequently references Henry James’s The Ambassadors (1903) throughout The Talented Mr. Ripley, with the narrative of the earlier novel serving as an inspiration for and influence on her work. James’s dark comedy follows fifty-something American Lewis Lambert Strether as he travels to Europe to persuade his fiancée’s expat son, Chad, to return home. Along the way, Lewis finds himself struck by Chad’s improved character and gradually grows accustomed to the European way of life.

I have not read this book and have it on the top of my TBR for September. Join me in reading it on the heels of The Talented Mr. Ripley, and stay tuned for thoughts! James’s Washington Square (1880) marks one of the most nuanced explorations of class I’ve read in recent memory, and I have no doubt The Ambassadors will capture those same contours.

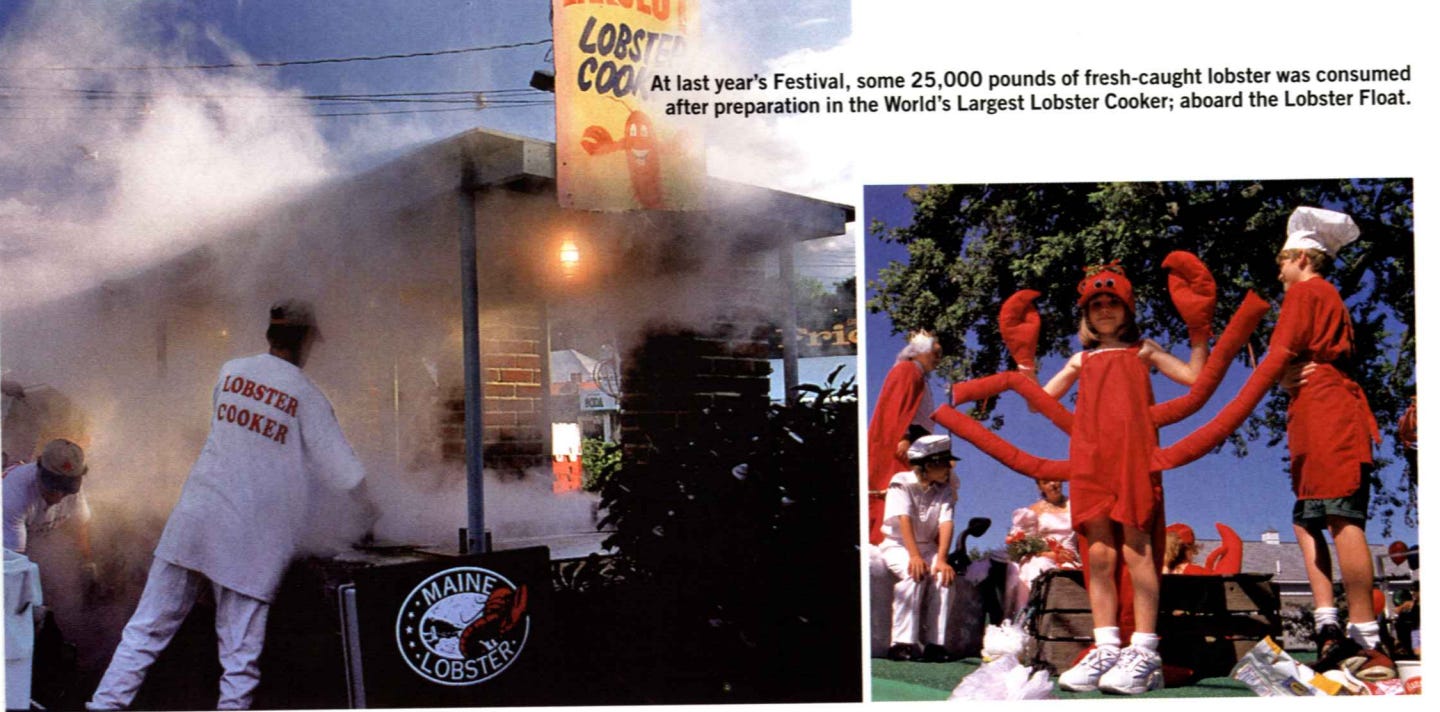

Consider the Lobster and Other Essays by David Foster Wallace (2005) — Let’s be real; we’re not going to read Infinite Jest (1996) this fall. Instead, pick up DFW’s acclaimed series of essays, which takes its name from his 2004 piece on the Maine Lobster Festival for Gourmet Magazine. In doing so, you’ll get a sense of Wallace’s detail-rich prose and unique perspective. My two favorite pieces in the collection center on two vastly different, but equally relevant, subjects: 9/11 and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

For the October 2001 issue of Rolling Stone, Wallace recounted the alienation of absorbing 9/11 from Bloomington, Indiana. Within the essay, he discusses the disconnect between urban and suburban cultures. For example, Wallace writes: “It thereupon emerges that none of the people here I’m watching the Horror with — not even the few ladies who’d gone to see Cats as part of some group tour thing through the church in 1991 — have even the vaguest notion of Manhattan’s layout and don’t know, for example, how far south the financial district and Statue of Liberty are; they have to be shown via pointing out the water in the foreground of the skyline they all know so well (from TV). This is the beginning of the vague but progressive feeling of alienation from these good people that builds throughout the part of the Horror where people flee rubble and dust. These ladies are not stupid, or ignorant…What the Bloomington ladies are, or start to seem, is innocent.”

Meanwhile, the second piece, first published in The Village Voice, operates as a review of scholar Joseph Frank’s multi-volume biography on Dostoevsky. This critique, simply put, made the Russian literary giant accessible to me when I first read it back in 2019. Wallace zeroes in on Dostoevsky’s grasp of humor, a detail often overlooked in discussions around his work, while also identifying how his writing captures people. Wallace explains: “The thing about Dostoevsky’s characters is that they live. And by this I don’t mean just that they’re successfully realized and believable and ‘round.’ The best of them live inside us, forever, once we’ve met them…[his] concern was always what it is to be a human being — i.e., how a person, in the particular social and philosophical circumstances of 19th-century Russia, could be a real human being, a person whose life was informed by love and values and principles, instead of being just a very shrewd species of self-preserving animal.”

Notes from a Dead House by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1860-2) — Let’s be real; we’re not going to read Crime and Punishment (1866) this fall. Instead, dip your toe into Dostoevsky with Notes from a Dead House (1860-2), a book you’ll feel especially equipped to read after exploring David Foster Wallace’s take on the Russian author. The novel, clocking about 300 pages compared to Crime and Punishment’s 500+, takes the form of a fictionalized memoir, one written on the heels of its author’s punishment for his involvement in the Petrashevsky Circle.

TLDR: Dostoevsky was part of a group of progressive intellectuals who faced persecution by the government for their embrace of Western philosophy and literature, a flavor of free thinking banned by Tsar Nicholas I (not to be confused with Tsar Nicholas II, last emperor of Russia; the Romanov family’s execution comes ~70 years later). Dostoevsky was arrested along with several of his friends, blindfolded in anticipation of an execution that never came. Instead, a letter from the Tsar announced a change in plans, a shift toward imprisonment, and Dostoevsky got shipped off to a labor camp in western Siberia. After his eight-year sentence got reduced to four, he returned to St. Petersburg and developed this novel based on his experiences.

As translator Richard Pevear writes in the foreword of my copy: “Notes from a Dead House…initiated the genre of the prison memoir, which unfortunately went on to acquire major importance in Russian literature. But the book was innovative not only in its subject matter, but in its composition…In the semi-fictional form he chose to give his narrative, Dostoyevsky places himself at a third remove. The fictional author-narrator of the Notes, Alexander Petrovich Goryanchikov, is a former nobleman serving a ten-year sentence for murdering his wife in a fit of jealousy.” Dostoyevsky writes with humanity, humor, and, above all, formal inventiveness. Pevear goes on: “His Notes are presented to us, in the introduction and in one brief intrusion in part two, chapter VII, by another first-person narrator, the ‘editor’ of Goryanchikov’s manuscript…with a mixture of heavy irony and underlying sympathy.”

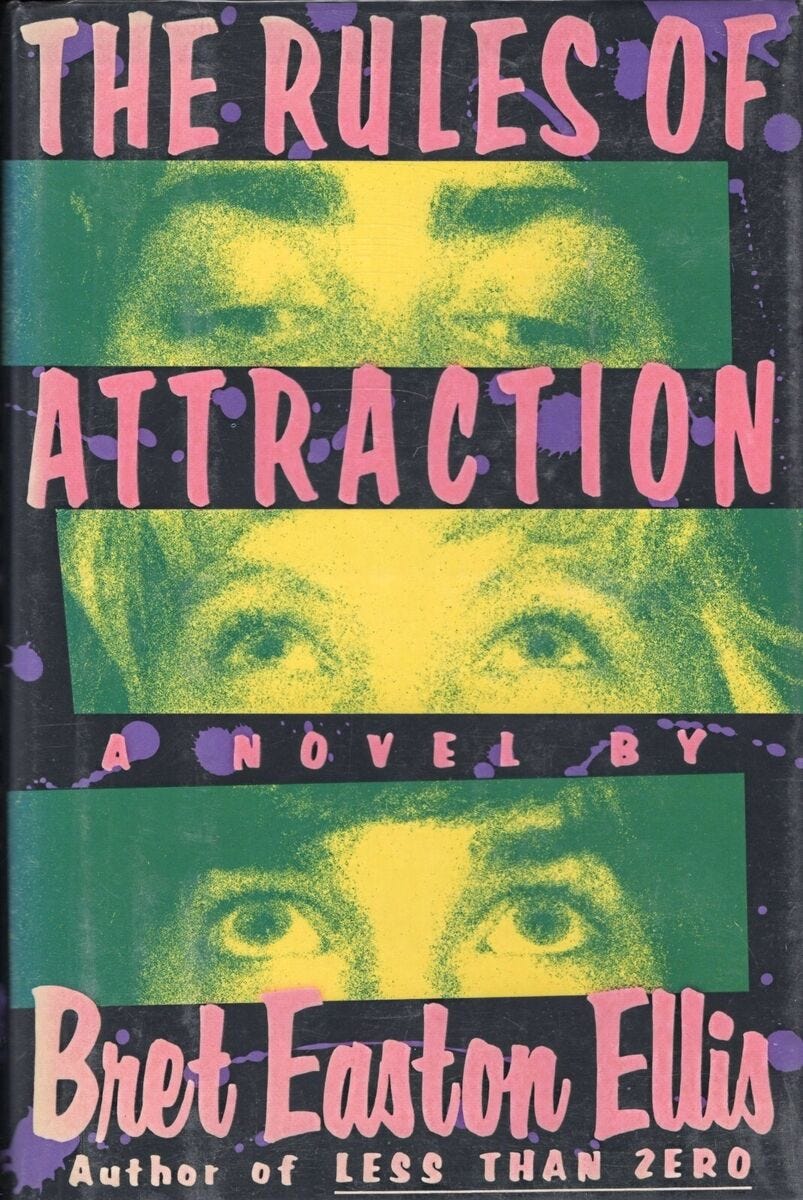

The Rules of Attraction by Bret Easton Ellis (1987) — Campus novel vibes!! Bret Easton Ellis’s Bennington novel owes its epigraph to novelist Tim O’Brien, opening with a quote from Going After Cacciato (1978) that reads: “The facts even when beaded on a chain, still did not have real order. Events did not flow. The facts were separate and haphazard and random even as they happened, episodic, broken, no smooth transitions, no sense of events unfolding from prior events —”

This excerpt sets the stylistic and narrative tone for The Rules of Attraction, a book that opens in the fall of 1985, in the middle of an exceptionally long sentence [“and it’s a story that might bore you but you don’t have to listen, she told me, because she always knew it was going to be like that, and it was, she thinks, her first year, or actually weekend, really a Friday, in September, at Camden, and this was three or four years ago, and she got so drunk that she ended up in bed, lost her virginity (late, she was eighteen) in Lorna Slavin’s room, because she was a Freshman and had a roommate and Lorna was, she remembers, a Senior or a Junior and usually sometimes at her boyfriend’s place off-campus, to who she thought was a Sophomore Ceramics major but who was actually either some guy from N.Y.U., a film student, and up in New Hampshire just for The Dressed To Get Screwed party, or a townie.”] Written in first person, the novel adopts the perspectives of each member in its love triangle — students Paul, Sean (Bateman, younger brother of Patrick Bateman lol), and Lauren. It embodies a kind of nihilistic eventlessness, evening out the importance of moments mundane and tragic, capturing the inconsequential loneliness that can define college.

Upcoming Content to Consume

Film Forum’s Spielberg Series (Dates: 9.1-9.12) — Film Forum’s Steven Spielberg festival continues this month! It consists of 20 films in 35mm, including classics like Jaws (1975), E.T. (1982), and Jurassic Park (1993) and earlier titles like Duel (1971) and The Sugarland Express (1974).

You can check out the full line-up here!

Opening Night (1977) in 35mm at The Paris Theater (Date: 9.4) — Pay homage to the late, great Gena Rowlands, who passed last month at age 94, with a screening of Opening Night (1977). Written and directed by her husband, John Cassavetes, the film focuses on an alcoholic actress days from the opening of her latest play. In his 1991 review, Roger Ebert praises Rowlands’s performance, her ability “to suggest, even in the midst of seemingly ordinary moments, the controlled panic of a person who needs a drink, right here, right now.” He also reflects on Cassavetes filmography more broadly, noting: “I love his films with the kind of personal urgency that you feel toward a beloved friend who is destroying himself. The films, taken together, are portraits of a crackup that is sustained, through courage and resiliency, for as long as humanly possible. Recovering alcoholics talk about ‘what it used to be like, what happened, and what it is like now.’ All of Cassavetes films are about what it used to be like, and for his doomed characters, nothing ever happens to make it any different now.”

The Paris Theater’s screening marks my top pick because it includes an introduction from filmmaker Azazel Jacobs, who, per the site, had the firsthand experience of seeing Cassavetes’s films with introductions from their leads, including Rowlands, while “working as a projectionist/ticket seller and popcorn maker at Le Cinematographe, a lower Manhattan movie theater.” But The Roxy Cinema in Tribeca will also screen Opening Night in 35mm on 9.27, with the added bonus of it playing back-to-back with Gloria (1980), another Cassavetes-Rowlands collaboration; you can check out details here!

McNally Jackson Seaport: Ross Benjamin presents The Diaries of Franz Kafka, in conversation with Elif Batuman (Date: 9.4) — To mark the publication of a new edition of Franz Kafka’s diaries, its translator, Ross Benjamin, will examine the Czech writer’s work and impact alongside Elif Batuman, author of The Idiot (2017) and Either/Or (2022).

Per McNally Jackson: “Dating from 1909 to 1923, Franz Kafka’s Diaries contains a broad array of writing, including accounts of daily events, assorted reflections and observations, literary sketches, drafts of letters, records of dreams, and unrevised texts of stories. This volume makes available for the first time in English a comprehensive reconstruction of Kafka’s handwritten diary entries and provides substantial new content, restoring all the material omitted from previous publications — notably, names of people and undisguised details about them, a number of literary writings, and passages of a sexual nature, some of them with homoerotic overtones. By faithfully reproducing the diaries’ distinctive — and often surprisingly unpolished — writing as it appeared in Kafka’s notebooks, translator Ross Benjamin brings to light not only the author’s use of the diaries for literary invention and unsparing self-examination but also their value as a work of genius in and of themselves.”

Having seen Batuman speak in the past, her persona lives up to her prose; she brings startling intelligence and humor to these types of conversations, bearing near-encyclopedic knowledge of philosophy, history, and literature. You can purchase a book and/or a seat for the event here!

Goodfellas (1990) in 35mm at Village East (Date: 9.9) — As I wrote when Metrograph screened this film last fall: “If you know, you know Goodfellas (1990) is one of my favorite films of all time. I’ve rewatched it with embarrassing frequency; read Nicholas Pileggi’s nonfiction book about Henry Hill, Wiseguy; and even have a t-shirt of a shot from the film showing Ray Liotta, Joe Pesci, and Robert DeNiro looking at a bag of cocaine (pictured above) that I wore wedding dress shopping with my friend (hi, Gabriela). With that context in mind, I feel legally obligated to flag this upcoming screening…If you’re not familiar, Goodfellas basically operates as The Godfather’s fun little brother. Told through the lens of real-life mobster-turned-witness-protection-participant Henry Hill, the Martin Scorsese classic captures the height of organized crime in New York from the 1950s through the 1980s.”

Casino (1995) in 35mm at The New Bev (Date: 9.18) — Goodfellas (1990) for New York subscribers, Casino (1995) for LA subscribers! I reviewed this film back in April, writing:

Casino fictionalizes Casino: Love and Honor in Las Vegas (1995) by Nicholas Pileggi, aka: the author of Wiseguy (1985), aka: the book that inspired Goodfellas (1990). With a script penned by Pileggi and Scorsese, the film takes the real-life story of Mafia associate, sports better, and professional gambler Frank Lawrence “Lefty” Rosenthal and recasts him as Sam “Ace” Rothstein (played by De Niro), while high-ranking Chicago mobster Tony Spilotro and showgirl Geri McGee become Nicky Santoro (played by Joe Pesci) and Ginger McKenna (played by Sharon Stone). As Ace navigates life as a Jewish casino owner in the Mafia-laden world of 1970s and 1980s Las Vegas, the line between friends and enemies begins to blur.

In both Goodfellas and Casino, friends that feel like family become enemies, and glamour belies grit. In a review for The Ringer, Adam Nayman notes how “long, clean dramatic lines of a tragedy and…slapstick humor” propel both films. But Casino adopts a distinctive tone compared to its predecessor, a quieter one that Nayman considers in that same review. He writes: “Goodfellas plays as a parody of a coming-of-age movie, with Henry simultaneously moving up the ranks and descending into a moral void; the key to [Ray] Liotta’s performance is that he plays him at all times like a callow, overgrown kid. Casino’s protagonist, though, is a grown-up. Ace is already middle-aged when the story begins in 1973, and he ages visibly through the narrative…With the earlier film, it’s as if Scorsese was trying for a show of youthful force…Casino has a few bravura set pieces and its own brand of filmmaking excitement…and yet the showmanship is judicious. The sensibility here is less exuberant than rueful, and carefully attuned to institutional systems of grift.”

Brooklyn Book Festival (Dates: 9.22-9.30) — Book fair vibes! Per the site, this multi-day event aims to “celebrate published literature and nurture a literary cultural community through programming that cultivates and connects readers of diverse ages and backgrounds with local, national and international authors, publishers and booksellers.” It includes multiple components, with a day of virtual panels on 9.22 and in-person programming at Borough Hall on 9.29.

You can learn more here!

Intermezzo Launch Day at Books Are Magic (Date: 9.24) — I am halfheartedly flagging the launch of Sally Rooney’s new novel, Intermezzo (2024), at Books Are Magic’s Smith Street location. While I loved Conversations with Friends (2017) and Normal People (2018), Beautiful World, Where Are You (2021) struck me as one-note autofiction primarily propelled by Rooney’s perpetual sense of global doom (valid) and irritation with the mechanics of the publishing world, an annoyance distilled and personified through the character of Alice. I also found the marketing circus around the launch (looking at you, bucket hats) eye roll-worthy. Anyway, as an overall fan of Rooney’s work, I’m holding out hope that this novel — centered on chess-playing brothers and their romantic entanglements — will hit better.

New York Philharmonic: Jaws (1975) in Concert (Dates: 9.26-9.28) — For the Spielberg super fans! This month, New York Philharmonic will kick off the latest season of its Art of the Score series — which, per the site, operates as “the ultimate ‘surround-sound’ movie event,” with “a legendary score…brought to life…while you watch the film on a towering screen above the Orchestra” — with a screening of Jaws (1975).

You can check out ticketing information here!

62nd Annual New York Film Festival (Opening Date: 9.29) — NYFF62 opens at the end of this month with a packed line-up of repertory screenings and new releases from around the world! Check out the full list here, and start planning your visit.

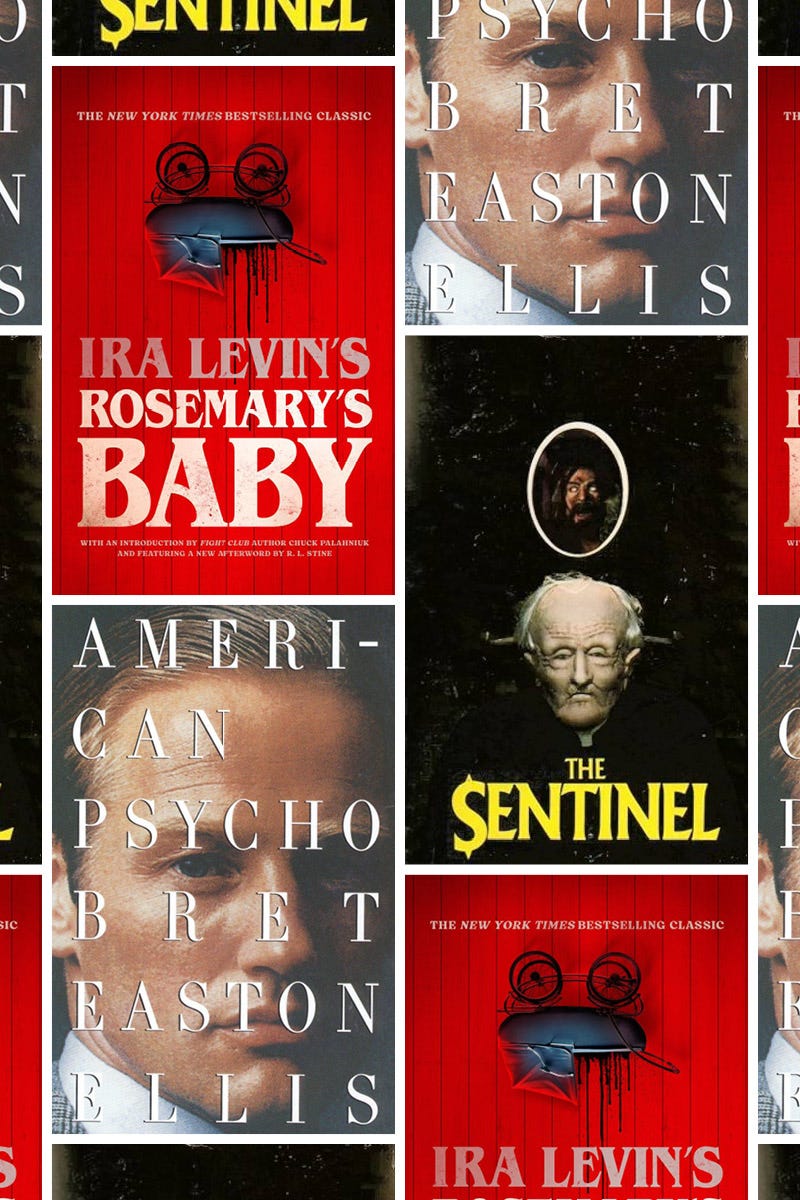

The Center for Fiction: Beyond the Tropes: Horror in New York City with Marc Abbott (Start Date: 9.29) — Held online through Zoom, this reading series will hone in on three New York horror classics — Rosemary’s Baby (1967), The Sentinel (1974), and American Psycho (1991) — across three decades — the 60s, 70s, and 80s, respectively — and start just in time for the lead-up to Halloween. Per the site, participants will “explore various themes and topics, including the dread and terror felt when moving to a new place, doubles and duality, and descents into madness. The tropes that weave these stories together tell a larger story as well. From overbearing neighbors to ‘it’s too good to be true’ apartments to the desire to be on top at any cost, these three novels helped change the landscape of horror.”

You can check out more details and, if you’re interested, sign up here!

Miscellaneous Musings

In My Ripley Era (cont.) — Ugh, my second favorite sociopathic white boy (with You’s Joe Goldberg taking the top slot, obviously). I first tried to watch this series before reading The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955) and struggled to get into it, mostly due to its sharp aesthetic departure from the 1999 film adaptation. After reading the novel, however, Andrew Scott’s Ripley has become my preferred embodiment.

Do I love the black and white palette? Not especially. Created with a Showtime budget, the series shot in color on Arri Alexa LF digital cameras and got converted to black and white as part of post-production. While this process achieves its intended effect, its goal of stopping the series from feeling like a postcard from Positano, it misses another opportunity entirely; had cinematographer Robert Elswit shot Ripley on film instead of digital, an approach Norwegian director Kristoffer Borgli is insisting upon for HBO’s upcoming adaptation of Bret Easton Ellis’s The Shards, the monochromatic palette would carry a transportive quality that its current presentation lacks.

But its aesthetic anachronism, the odd effect of black and white on digital, pales in comparison to how faithfully it enlivens Highsmith’s text, to the quality of its Emmy-nominated lead’s performance. In her review for The Guardian, TV critic Lucy Mangan writes: “It…moves incredibly slowly. For those who can lean in and appreciate the capture of a sensibility summarised in Graham Greene’s description of Highsmith as a ‘poet of apprehension,’ this will be one of the best things about it. The careful mapping of Tom’s every move, whether in furtherance of his deceit or the covering up of his crimes, allows the tension to mount exquisitely.” She goes on: “At the heart of it all, and in virtually every scene, is Scott. He has said in interviews that he didn’t want to diagnose or define Ripley too closely, which could have been a recipe for either blandness and confusion. Instead, it makes him a wellspring of possibilities…Scott’s Tom is everything and nothing, and mesmeric either way.” +2!!

Jay McInerney Musings — Air Mail recently made me aware that literary brat pack ringleader Jay McInerney, author of Bright Lights, Big City (1984), has a COVID novel in the works, which lol. After reading this new Q&A looking back on his debut novel, I wandered down a rabbit hole on McInerney, including reading his 2016 Art of Fiction interview in The Paris Review. It spans a number of topics, but the most compelling touchpoint, to me, centers on perspective. ICYMI: Bright Lights, Big City garnered attention on publication for not only its capture of cocaine culture, but also its second-person narration. McInerney explains:

INTERVIEWER: Did you ever try to write in the second person again?

MCINERNEY: I’ve thought many times about doing it again. I just haven’t found another story, another situation that could lend itself to the second person. I loved writing in that voice. I wish I’d hear a voice like that again.

INTERVIEWER: Your third novel, Story of My Life, about party girl Alison Poole, isn’t in the second person, but it has a similar focus and intimacy.

MCINERNEY: There, too, I don’t want to get mystical, but I heard a voice, a voice in my head, and it propelled the writing. Both books had a sense of rhythm and music that made them a pleasure to write and that I hope is the reason people like to read them. And it was really fun to put on a pair of high heels, as it were, and a black cocktail dress and step out in a completely different persona. None of my subsequent novels has been so effortless. The others felt like work.

INTERVIEWER: Is that because you couldn’t find a voice to carry you through?

MCINERNEY: It was also because I became more ambitious. I wanted a bigger canvas. So of necessity, a lot of my subsequent novels were written in the third person — the creation was more self-conscious, more cerebral, less visceral somehow. And there are things you can do in your twenties that you can’t do later. There is a music of the spheres that you only hear in your twenties. I don’t necessarily think Bright Lights and Story of My Life are my best books, but they were the most fun to write. They may be the most fun to read, I don’t know.

This excerpt, to me, underscores the nuance of perspective in fiction, of authors putting thought into the voice that drives their narratives. For example, think of how differently Jeffrey Eugenides’s The Virgin Suicides (1993) would read without its Greek chorus of men looking back on boyhood. Recommending the novel back in March, I wrote: “By carving out this collective narrative voice, Eugenides underscores the girls as local legends, as a microcosm of the spectatorship that surrounds girlhood. In her 2018 introduction, [author] Emma Cline [understands the novel as] ‘an elegy for how life passes through us…there is no memory that doesn’t fuzz around the edges.’ The book blurs the distinction between childhood and adulthood, reveals how the former refracts but refuses to fade.” The Virgin Suicides’s nostalgic texture remains predicated on its narrative voice, reflecting the value of intentionality in perspective that McInerney’s interview reflects.

Supplemental Reading

As always, don’t forget to use archive.ph if you can’t access these pieces or any of the ones throughout my Substack!

Variety: Gena Rowlands Remembered: How A Woman Under the Influence Transformed the Craft of Screen Acting

Air Mail: The Many Lives of Alain Delon

The Paris Review: Notes from a Dead House

The New Yorker: “Opening Theory” by Sally Rooney

The New Yorker: Sally Rooney on Characters Who Arrive Preëntangled and Her Forthcoming Novel

Social Media Round-Up

A new section aggregating tweets, TikToks, Notes, etc. that made me laugh in the past month:

Cocktail of the Month

We’re mentally in Italy this month with the…

Huge shout out to my friend Mehul (hi, Mehul!) for recommending this cocktail. To make it, add one and a half ounces each of Cynar and Amaro Montenegro to an iced cocktail shaker, followed by three-quarters of an ounce of lime juice.

Shake well, and strain into an iced cocktail glass. Then, top with two and a half ounces of ginger beer, and enjoy!

That’s all for now! Stay tuned for the July and August Movie Reviews!

xo,

Najet

BEE x Patricia Highsmith ... my two favorite evil gay novelists <3333