Movies of the Month: April

On 1960s French and Italian cinema, plus a Bonjour Tristesse double feature

In April, I watched Claude Lelouch’s A Man and a Woman (1966) and Federico Fellini’s 8½ (1963) at Film Forum, ironically both starring iconic French actress Anouk Aimée. Then, I saw a preview of Durga Chew-Bose’s Bonjour Tristesse (2025) and streamed the 1958 Otto Preminger adaptation as a comparison point a la the month I watched both Cape Fears.

Let’s get into it:

A Man and a Woman (1966, dir. Claude Lelouch) — As a wise rando on Letterboxd put it, “When I tell people my favourite genre is french people falling in love and being sad this is exactly what I mean.” SO true.

Winner of the 1966 Palme d’Or, A Man and a Woman (1966) follows Anne Gauthier (played by Anouk Aimée) and Jean-Louis Duroc (played by Jean-Louis Trintignant) as they navigate new love. Both divide their time between Paris and Deauville, a seaside town in Normandy where their respective children — Anne’s daughter, Françoise (played by Souad Amidou), and Jean Louis’s son, Antoine (played by Antoine Duroc) — attend the same boarding school. One day, Anne misses the train, and Jean-Louis offers her a ride back to the city. A quiet connection sprouts between the pair, launching a non-linear narrative that pieces together the question of their lives beyond each other — and, within that, the status of their relationships with their respective spouses.

Filmmaker Claude Lelouch infuses A Man and a Woman (1966) with atmospheric tenderness, punctuated by Francis Lai’s melancholic score, one of the greatest of all time. Closely cropped shots — of glancing eyes, of brushing hands — magnify the connection between Anne and Jean-Louis. Memory fills contextual holes, serving as both characters’ primary emotional catalyst. Without spoiling specifics, the film bubbles toward a boiling point wherein Lelouch cuts together images of past and present, revealing the full scope of Anne’s fragmented inner life. As Wilson Chapman writes for an IndieWire piece ranking Palme d’Or winners, A Man and a Woman offers “a touching, realistic look at a burgeoning adult romance, with each participant encumbered by a past tragedy, causing them to proceed delicately.”

Where to Watch: Film Forum through 5.1, Amazon Prime Video (premium subscription), Tubi (subscription)

8½ (1963, dir. Federico Fellini) — A cinematic masterpiece, Federico Fellini’s 8½ (1963) inhabits the headspace of Italian director Guido Anselmi (played by Marcello Mastroianni). In the midst of shooting his forthcoming science fiction epic, Guido grapples with director’s block, a creative crisis that reflects a midlife one. He hires film critic Carini Daumier (played by Jean Rougeul) to review his ideas, an abundance of possibilities slipping from his grasp, met with complete rejection rather than constructive criticism. Autobiographical details litter the film within a film, making its failure all the more personal as Guido balances having his estranged wife, Luisa (played by Anouk Aimée), within yards of his mistress, Carla (played by Sandra Milo). As Roger Ebert writes, “the movie is the portrait of a man desperately trying to weld together the carnal and spiritual sides of his nature; the mistress and the wife, the artistic and the commercial.”

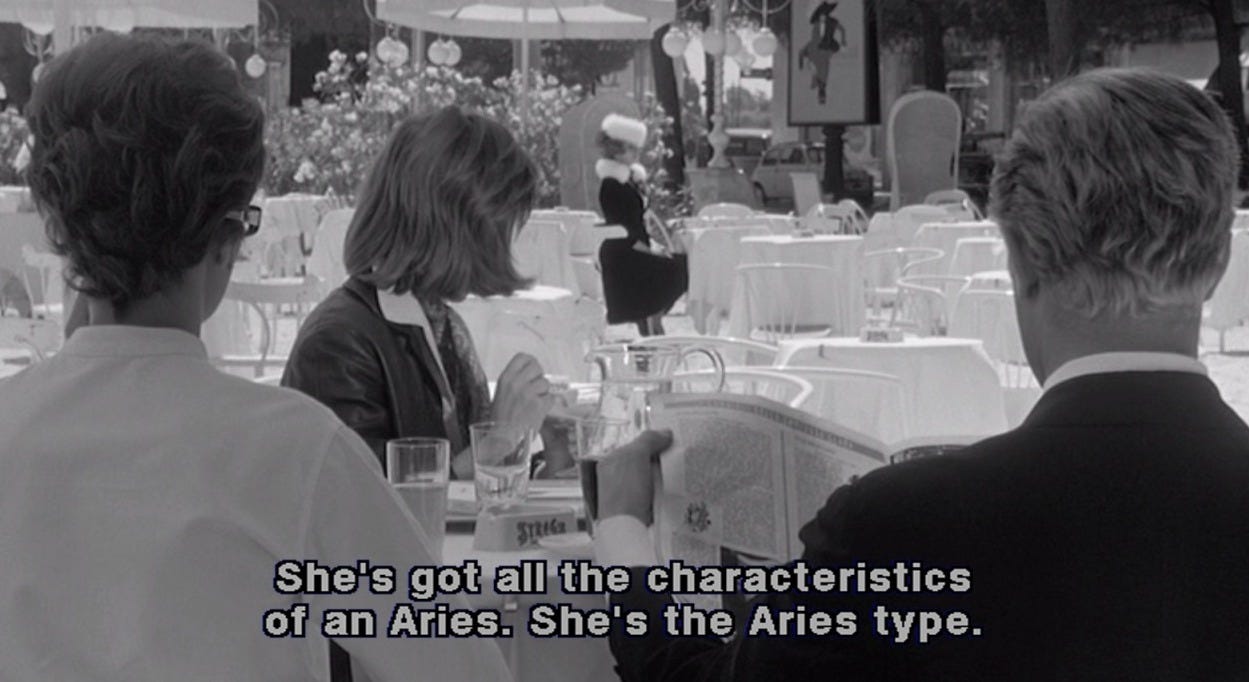

In keeping with that sense of duality, 8½ blurs the line between reality and imagination. Dream sequences, funhouse reflections of Guido’s innermost preoccupations, pepper the film. One vision crowds every woman Guido has slept with — or wanted to sleep with — into the same space, magnifying his failures in fidelity. His wife’s best friend, Rossella (played by Rossella Falk), announces herself as Guido’s personal version of Pinocchio’s cricket, critiquing what she calls his harem. As Ebert describes: “They all love him and forgive him, and love one another. But then there is a revolt, and he cracks a whip, trying to tame them. Of course he cannot.” A pinprick of surrealism accentuates each character, feeds into an undercurrent of absurdity. For instance, Carla possesses a deliberately cartoonish quality. In one scene, her eyebrow paint quite literally goes sideways, and erratic lines brand her face for the rest of the evening.

Fellini serves as an artistic and intellectual forbearer to the late great David Lynch. They met twice. An affinity emerged, rooted in their shared birthday (both have Capricorn stelliums lol??) — and interest in visual art. Fellini began his career as a cartoonist, while Lynch pursued painting at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Both then adjusted their ambitions toward filmmaking. Their second encounter came in the form of a 1993 visit to a Roman hospital. Lynch recalls: “I went and sat. Fellini held my hand, and we talked for about a half an hour.” Days later, Fellini fell into a coma and never recovered. In their filmmaking, the two men refract the world through a surrealist lens. Where confusion engulfs 8½’s Guido, Fellini architects his directorial vision with precision, prefiguring and pioneering the Lynchian lexicon.

Where to Watch: Film Forum (in 35mm) through 5.8, Criterion Channel (subscription), Max (subscription), Hulu (premium subscription), Amazon Prime Video (premium subscription)

Bonjour Tristesse (2025, dir. Durga Chew-Bose) — Legendary Austrian-American director Otto Preminger — the mastermind behind Laura (1944), The Man with the Golden Arm (1955), and Anatomy of a Murder (1959), among others — first adapted Françoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse (1954) for the screen in 1958 (more on that in a minute). The novel, a slim debut from 18-year-old Sagan, became an overnight sensation when it first published in 1954. Narrated from the perspective of 17-year-old Cécile, it traces a summer spent on the French Riviera, a peaceful period disrupted by the arrival of her deceased mother’s old friend, Anne. Her closeness to Cécile’s father, Raymond, threatens the status quo. Cécile’s freedom erodes alongside Raymond’s relationship with his girlfriend, Elsa, prompting Cécile to enact a childish scheme that ends in tragedy.

Now, for her feature-length debut, Canadian critic and essayist Durga Chew-Bose has reinterpreted Sagan’s melancholic coming-of-age story for the present day, a sun-soaked interpretation punctuated with iPhone exchanges and tangled headphones. Ahead of the theatrical release on 5.2, I saw a pre-screening of Bonjour Tristesse (2025), which first premiered at TIFF last fall, at L’Alliance on the Upper East Side.

Bonjour Tristesse (2025) bears certain similarities to Luca Guadagnino’s Call Me By Your Name (2018). Where Chew-Bose draws from Sagan’s text, screenwriter James Ivory adapts from André Aciman’s eponymous 2007 novel. Laced in lazy heat, both films stay faithful to the narrative beats of their source material; each main character, Cécile (played by Lily McInerny) in Bonjour Tristesse (2025) and Elio (played by Timothée Chalamet) in Call Me By Your Name (2018), undergoes a transformative summer, their post-coming-of-age emotional state revealed through a cold weather coda. Each novel adopts a first-person perspective, but Chew-Bose and Guadagnino differ in how they bring that point of view to the screen.

In Call Me By Your Name (2018), Elio guides every scene. The audience experiences a slow, vicarious descent into lust, then love. His vision colors the people around him, from his parents to the object of his affection, Oliver (played by a pre-cancellation Armie Hammer). Guadagnino’s tight grasp on Elio’s viewpoint cultivates an emotional affinity between audience and character, one that reaches a crescendo in the film’s final sequence.

Conversely, in Bonjour Tristesse (2025), Chew-Bose presents an imprecise perspective. Cécile floats in and out of scenes, suggesting a third-person camera lens. Cécile’s inner life stays distant, then erratic and indiscernible in the last half hour, but her view colors every character. For example, Anne (played by Chloë Sevigny) functions as a caricature, the embodiment of an evil stepmother archetype, without the rationale of Cécile’s first-person perspective. Anne’s emotional life remains hidden until the film’s final moments (through no fault of Sevigny’s), the exact image that causes her hurt obfuscated even then.

Bonjour Tristesse (2025) suffers from a severe lack of dialogue. In Otto Preminger’s 1958 adaptation, the image that upsets Anne in the film’s final moments remains offstage as well. But what she hears bleeds into the audience’s ears too, clarifying the exact texture of her sorrow. Beyond this moment, actions occur in a vacuum. Preminger shows Cécile, Raymond, Elsa, and Anne discussing an upcoming party, one rife with gambling that Elsa plots to dominate. Meanwhile, Chew-Bose reveals her cast getting ready for, then at, her equivalent of that party with no narrative build-up, diffusing tension from what should be one of the film’s most climactic scenes.

Chew-Bose’s adaptation shines in its aesthetic sensibility. Summer light litters Raymond (played by the incredibly hot Claes Bang) and Cécile’s home, with close-ups of waves, of sand, shaping the sun-soaked setting. Particular actions reflect unspoken conflict. For instance, one sequence shows Cécile and Elsa (played by Aliocha Schneider) biting into a pair of apples, while Anne cuts hers with a knife. This moment shows a split in sensibilities between the women, while revealing their alliances. But these choices appear stripped of emotional intent. Chew-Bose over-indexes on the oft-espoused advice to show rather than tell, and shots straight out of Tumblr supplant exploration of inner life, siphoning out any semblance of tension.

Where to Watch: IFC Center starting on 5.2

Bonjour Tristesse (1958, dir. Otto Preminger) — Sizzling with tension, Bonjour Tristesse (1958) captures its characters’ motivations with a precision that the new adaptation lacks. Where Durga Chew-Bose features multicolored tiles for her opening sequence, their function an aesthetic one, Otto Preminger begins with title cards designed by Saul Bass [known for creating the title sequences from Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959), and Psycho (1960) to Goodfellas (1990), Cape Fear (1991), and Casino (1995)]. As author Pat Kirkham writes in Saul Bass: A Life in Film and Design (2011), the sequence closes with “a haunting face created from a few brushstrokes…[capturing] the elusive delicacy as well as the sadness that lies at the heart of the film. It previews the film's narrative, from the lost innocence of adolescence to the sadness that knowledge and adulthood bring to the young woman.”

Preminger’s narrative vacillates between past and present, opening in Paris. Cécile (played by Jean Seberg) prepares for an evening out alongside her father, Raymond (played by David Niven). They arrive at a party, and Cécile dances with a boy; a voiceover announces her inner emptiness, a melancholia brought about by the events of the prior summer. This opening scene thrusts the film squarely into her first-person perspective, a clarity missing from the 2025 adaptation. French performer Juliette Greco sings “Bonjour Tristesse” as black and white blisters into color, and the timeline jumps backward a year, the location south. A lighter, younger Cécile — overacted by Seberg at points, but never horribly so — bounces around her and Raymond’s villa on the French Riviera. She wears a red bathing suit and an oversized blue shirt tied up into a knot to match her father, their bond still buoyant.

In Bonjour Tristesse (1958), the texture of the relationship between Cécile and Raymond maintains a unique specificity. Where Claes Bang’s Raymond still bears the weight of his wife’s death, David Niven’s Raymond remains unencumbered. The quintessential midcentury playboy, Niven’s Raymond soaks in life’s finer things. He eschews responsibility, rarely reading the telegrams he receives no matter how urgent, and approaches Cécile as more friend than daughter. Meanwhile, Cécile harbors a kind of Electra complex. She and Raymond maintain an uncomfortably high-touch relationship and, when Anne (played by the incomparable Deborah Kerr) enters the picture as a potential partner for her father, Cécile views her as a direct rather than existential threat. Case in point, one scene shows Cécile making a chart that compares her and Anne’s various qualities, ranking them through the lens of who offers a net better presence for Raymond.

A kind of Eloise, Cécile inhabits a charmed existence freed from the burden of adult responsibility. Preminger approaches the character with greater fidelity to her literary counterpart than Chew-Bose does, distilling the qualities that distinguish her in Françoise Sagan’s original text. Vain, precocious, and passionate, Jean Seberg’s Cécile exudes the kind of hot-headed immaturity that Lily McInerney’s Cécile, on paper rather than through performance, lacks. In the 1958 adaptation, Cécile’s resentment toward Anne stems from not only the arrival of order, but also a forced reckoning with self-awareness. At one point, examining her reflection in the mirror, Cécile declares: “Anne had made me look at myself for the first time in my life. And that made me turn against her. Dead against her.” This recognition adds a layer of depth to the growing gulf between the two women, one rooted in inner life as opposed to just outer circumstances.

In the 2025 adaptation, Anne’s arrival brings no joy; it marks a disruption of the dynamic between Raymond, Elsa, and Cécile without any semblance of a silver lining. Raymond and Elsa (played by Aliocha Schneider) appear as true partners, with no mentions (that I can recall) of his past flings. Meanwhile, the temporality of Mylène Demongeot’s Elsa becomes evident from the outset. Cécile expresses gratitude that Raymond’s girlfriend from the fall didn’t make it to the summer, considering Elsa a far better fit for their seaside escape. This comment situates her as a cog in the broader machine of Raymond and Cécile’s shared life, whereas, when Elsa gets discarded in Chew-Bose’s version, a stone-cold mistress supplants a pseudo-mother.

Deborah Kerr’s Anne carries more nuance than Chloë Sevigny’s; both actresses give skilled performances, but Chew-Bose’s writing ties Sevigny’s hands. Sevigny’s Anne comes with a concrete veneer that cracks, just barely, in the film’s final moments. McInerney’s Cécile resents her from start to finish, casting the sudden sentimentality that flashes through Chew-Bose’s final act as befuddling. In Preminger’s adaptation, Cécile feels overjoyed at Anne’s arrival, perceiving her as a kind of godmother. Elegant and serious without severity, Kerr’s Anne brings an approachable order to their home that Seberg’s Cécile welcomes. The texture of their relationship shifts only when she creeps into the role of stepmother, encouraging Cécile to study with the parental force Raymond disavows. A complexity of feeling crystallizes on both sides, and tenderness bubbles beneath frustration and resentment.

Chew-Bose wraps the relationship between Sevigny’s Anne and Bang’s Raymond in the past above all else, making his choice between her and Elsa an arbitrary one. Meanwhile, in the 1958 version, the relationship between Kerr’s Anne and Niven’s Raymond sizzles with not only hidden history, but also present chemistry. She arrives at the sea shocked to find another woman there in the form of Elsa, lured into the false promise of romantic pretense. Their sexual connection carries a romantic, emotional layer, one missing from his relationship with Elsa; plus, in this iteration, Raymond and Anne have fun together. But, bound by libido, he tries and fails to outrun his own impulses. The summer becomes a coming of age crux for not only Cécile, but also Raymond. As the narrative flashes between past and present, Preminger casts father and daughter as two empty actors doomed to maintain the facade of their light and breezy life, cursed by the unspoken emotional hole at its center.

Where to Watch: YouTube TV (premium subscription), Amazon Prime Video ($3.99)

To close, please enjoy my favorite sun protection looks from Aliocha Schneider’s Elsa as we gear up for summer:

Okay, that’s all for now! Stay tuned for the April Book Review and May newsletter.

xo,

Najet

In this context - here is my remembrance of some European movies from the 1970s:

https://open.substack.com/pub/tarikzukic/p/fragments-of-one-cultural-history?r=yckeo&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

Nice writing, thank you.

Now 58, I have watched those movies in some other times, but not in the years of their initial releases. The projection of Un homme et une femme I watched in early 1980s, from a poor copy in a small town theatre in Bosnia. In the early 1980s the movie was at the lowest point of its cultural importance, everything on the screen was outdated and obsolete: from the brownish clothes and boss-nova songs to the excessive sentimentality of the story and the cinematic tricks such as showing windshield vipers by driving through a rainy night.

...but I loved it and this is still one of my favourite movies.