Tbh, I could have had this one to you all sooner, but I was busy this last week rewatching the third season of Beverly Hills, 90210 doing important fiction research on the early 1990s.

Anyway, I started January with My Heavenly Favorite (2024), an early aughts retelling of Lolita (1955) through the lens of an agriculture farmer obsessed with a nonbinary child. Then, I read I Am Alien to Life (2024), a collection of Djuna Barnes short stories from McNally Editions edited by Merve Emre, as well as two wonderful new coming-of-age novels set in 1980s New York: Adam Ross’s Playworld (2025) and Cynthia Weiner’s A Gorgeous Excitement (2025).

Let’s get into it:

My Heavenly Favorite by Lucas Rijneveld (2024) — As journalist Francesca Peacock writes in her LARB review: “It’s surreal to review a book that made you feel physically sick. It’s even more surreal to give a book that made you feel that way a good review, to say that the nausea was somehow positive or warranted. But that’s the bind when writing about Lucas Rijneveld’s horrifying and brilliant sophomore novel, My Heavenly Favorite (2024).”

Translated from Dutch by Michele Hutchison, My Heavenly Favorite takes the form of a 330-page confessional. Told in the second person, it adopts the perspective of “Kurt,” an agricultural veterinarian who operates as an early-aughts answer to Vladimir Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert. Kurt works for a family haunted by loss, by a missing matriarch and deceased child, the latter a hole at the hands of a hit and run. Its remaining members include the farmer, his late teenage son, and his 14-year-old daughter, all unnamed. Kurt forms a fixation with and begins to groom the unnamed girl, with the novel itself taking the form of a letter to her, to the ladies and gentlemen of the jury, after he faces conviction.

Stylistically, My Heavenly Favorite operates as a direct descendent of Nabokov’s Lolita (1955). Both novels inhabit the headspace of a sick narrator, a sexually stunted predator, through the prism of stunning prose. But Rijneveld takes Nabokov’s narration a step further by eliminating paragraph breaks and periods a la Vigdis Hjorth. As I write in my review of Hjorth’s Will and Testament (2016), “commas substitute periods, shaping the looping hyper-fixation that comes to define of [narrator] Bergljot’s stream of consciousness (‘I tried to open my mind towards Lars so that his harmless dreams could flow into mine, I tried to suck the dreams out of his sleeping body, but it didn’t work, there was no way in, I was trapped inside myself.’).” The same characterization applies to Kurt’s narration in My Heavenly Favorite, with the sentences that shape his “looping hyper-fixation” double the length by comparison.

Rijneveld’s references span the biblical to the cultural, with the novel’s primary action transpiring over the summer of 2005. Peacock explains: “This is a world of the censorious Reformed church…Rijneveld’s prose is peppered with snatches from psalms, italicized and gruesome-sounding, estranged as they are from their original, spiritual context. When the vet describes his wife Camillia’s reaction to the child apologizing for her relationship with him, he quotes Psalm 137.” Meanwhile, the girl worships the work of Roald Dahl, listens to blink-182 and Kate Bush, and nicknames the narrator after Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain. She maintains the fear that she caused 9/11, the conviction that her shared birthday with Adolf Hitler, April 20th, conceals an unknown evil. Kurt narrates:

“…you told me you had flown there that tragic September day and you’d heard the people’s screams beneath you, the sirens, and as you flew, office papers streaming out of the towers became doves of peace and you saw people launching. themselves out of windows, you heard the dull thuds of the landing bodies like bags of milk powder, and then a second plane pinned itself to the second building of the Twin Towers an you wondered whether it was a plane or whether you had flown into that building, first with your head, your torso, and then the rest of your body, your feet, you thought it was all your fault, and I saw the tears welling behind your eyes and I thought, man, you were only ten then, but I let you tell me about how you often fantasized that a plane would crash into De Hulst farm and you’d hear the walls fall down, the glass shatter, and you saw your dad lying under the right-hand wing even though they’ been aiming at you, you said…”

Disembodiment defines the girl; she has little sense of her physical self, within and beyond the confines of a gender binary. Kurt takes advantage of this dysphoria. His manipulations stem from his promise of more knowledge of, more access to, the male body. (She never explicitly identifies as male or nonbinary, hence why I’ve continued to use she/her pronouns throughout this review.) For instance, he coaxes her into their first sexual encounter by promising it will deliver on her desire to grow a penis. Her confusion clouds the reality of their relationship until summer draws to a close, and the fact of his abuse calcifies.

Kurt addresses his musings to not only her, but also the jury that has sentenced him to two years in prison. She grows up to become a singer, and the courts use not only her diary, but also her first record, entitled Kurt12 “after the case number,” as evidence. As Peacock writes toward the end of her review: “The music, the case — none of it allows the girl to move on…My Heavenly Favorite remains mired in horror…toying with memory, with history, with the idea that writing or producing art can ever possibly change anything.”

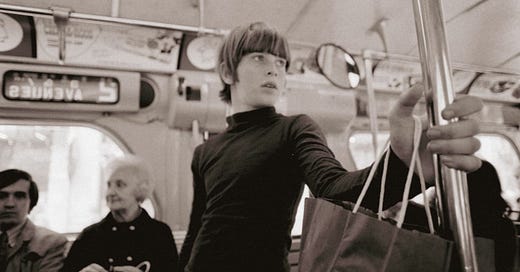

Playworld by Adam Ross (2025) — An absolute time capsule of a novel from Sewanee Review Editor Adam Ross, Playworld (2025) follows a year in the life of Griffin Hurt, a child actor growing up on the Upper West Side. It begins with a prologue that starts: “In the fall of 1980, when I was fourteen, a friend of my parents named Naomi Shah fell in love with me. She was thirty-six, a mother of two, and married to a wealthy man. Like so many things that happened to me that year, it didn’t seem strange at the time.” As Helen Schulman writes in her Air Mail review, that opening sets the tone for the 500 plus pages ahead as “Griffin experiences a lifetime of damage and blind endurance crammed into one extremely long, harrowing year. At 14, he is a successful actor by accident, having lucked into an enormous native talent he shrugs off as a combo of filial duty (his father is also a performer), a propensity for de-personalization, and a survival skill.”

As the sun sets on the Carter administration and rises on the Reagan era, Griffin balances his role as Peter Proton on hit TV show The Nuclear Family with wrestling, his course load at Trinity avatar Boyd Prep, and the world of adults that presses up against his latchkey childhood (“Adults were the ocean in which I swam.”). The adults that swirl through his view include “his narcissistic father, Shel, who struggles to support the rest of the family by doing voice-overs and jingles of the household-product variety while craving meatier roles,” per Schulman; his mother, Lily, a perennially honest professional dancer-turned-Pilates instructor with an Master’s degree in Literature; predatory wrestling coach Kepplemen; and, of course, Naomi, who perpetually retreats and reemerges over the course of the narrative. As Schulman also notes: “All four Hurts — there is a loyal younger brother, Oren, with built-in street smarts and no over-obvious aptitudes — see the same therapist, who is also Shel’s best friend, Elliot.” (“In our house, Elliot was referred to so often it was a bit like belonging to a cult.”)

Much like Bret Easton Ellis’s latest book, The Shards (2023), Playworld gets narrated from the first-person perspective of its primary character — but an older version of him. Ross more or less maintains a child’s perspective, zooming out on occasion for the sake of contextualization; this vacillation affords a welcome balance of innocence and insight (“It was all more Apollonian than Dionysian, and it was exemplified by the distinctly Neverland quality to how we partied. As was the case with Gwyneth, spending all night out at Studio 54, we were impersonating the adults it seemed we only knew from afar.”). Speaking at McNally Jackson Seaport, Ross likened the novel to an aquarium. While 14-year-old Griffin floats through his life, certain scenes sharpen into the forefront, his older self serving as a kind of tour guide.

Similarities between The Shards and Playworld span beyond their narrative structures. Ross describes his new novel as “rhyming” with his life, a notion that equally applies to Bret’s serial killer-infused reanimation of his senior year. Both narratives deal in dense doses of nostalgia, something that, for me, feeds their compulsive readability. Bret enlivens Los Angeles circa 1981, from The Sherman Oaks Galleria on a fall afternoon to Mulholland Drive at midnight. Ross captures comparable corners of New York (“Fall in full swing now, the trees in Lincoln Towers’ green space shed their leaves; beneath awnings, the heat lamps shined on passing pedestrians and conferred on them an orange rotisserie glow.”). He describes Playworld as a map of a “lost city,” what Bret would call the last gasps of American empire.

Like The Shards, Playworld has a loose shape that becomes one of its distinguishing factors, imbues it with the texture of life. As New York Times Book Review critic Alexandra Jacobs points out, Playworld “is detailed, digressive, densely populated, dull at times (as life is) and capable of tracking the most minute shifts in emotional weather. It is the young and the restless, edging into the bold and the beautiful.” She explains:

It’s not the play that’s the thing in Playworld — a gorgeous cat’s cradle of a book that sometimes unravels into shaggy-dog stories — but the lines, in every sense of the word. The marketing taglines that bear the same force and resonance as elders’ aphorisms: 1010 WINS, American Express, Calgon. The lines between juveniles and adults blurring and being crossed. And Ross’s own refined lines, his powers of observation and ironclad resistance to cliché yielding perfect descriptions again and again. A crowd of Nightingale-Bamford girls makes “a sound between laughter and slaughter, as if the school itself were shouting.” Central Park is “that mood ring in the middle of Manhattan.” By the grace of Ross’s language, even a seasick sailor’s trail of vomit descending off a warship into the ocean takes on — I swear it — a certain crystalline beauty.

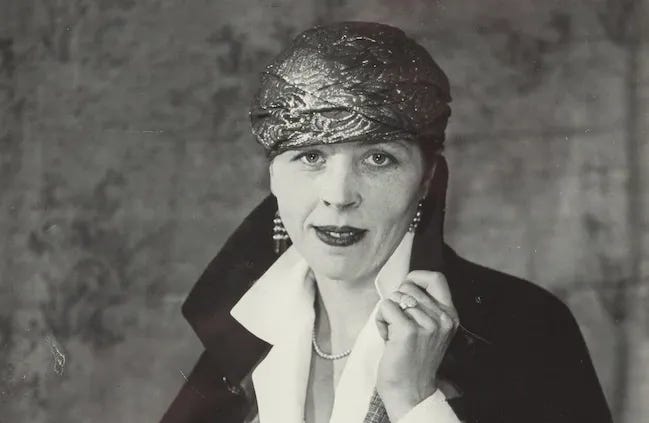

I Am Alien to Life: Selected Stories by Djuna Barnes (2024) — This new collection from McNally Editions, edited by critic and New Yorker contributor Merve Emre, aggregates a series of short stories from modernist writer Djuna Barnes. Per McNally Editions, “Barnes is rightly remembered for Nightwood (1936), her breakthrough and final novel: a hallmark of modernist literature, championed by T. S. Eliot, and one of the first, strangest, and most brilliant novels of love between women to be published in the twentieth century. Barnes’s career began long before Nightwood, however, with journalism, essays, drama, and satire of extraordinary wit and courage. Long into her later life, after World War II, when she published nothing more, it was her short fiction above all that she prized and would continue to revise.”

I Am Alien to Life (2024) deals with love and loss of innocence, its stories often ending in death. Acute flashes of emotion create consistency across the narratives, and subtle humor belies each piece; as Emre points out in her foreword, “Dr. Silverstaff is a fantastic name for a gynecologist.” As she goes on to describe, “most of the stories are told in the third person by a narrator who possesses a profound understanding of the human condition, an understanding that is hinted at, but never revealed.” The third-person pieces tease out pastoral nightmares, vignettes of people realizing the terror of the countryside; tales of immigrants losing their innocence; and doomed, often queer, love stories. The remaining narratives take the form of what Emre calls “first-person soliloquies…their compulsion to narrate…borne of the desire to remember a past that everyone else would rather forget…Plot is not Barnes’s strength, although it is difficult to know whether its construction fails to hold her interest or because, in the end, all plots — all lives — dead-end in the same revelations, the same drives.”

Barnes’s prose adopts a strange syntax, designed to reflect her characters’ alienation (“There in the corner sat Freda’s mother with her cats. She always sat in corners, and she always sat with cats. And there as the rest of the cast — cousins, nephews, uncles, aunts.”). The people she enlivens occupy certain categorical types that recur across the collection: the wealthy woman grappling with an ill-fated love; the child pressing up against the edges of the adult world; the man who has “an odor about him of the rather recent cult of the ‘terribly good,’” his opposite “who can turn the country, with a single gesture, into a brothel.” Per Emre, Barnes’s “characters may be alien to life, but they are alive — spectacularly, grotesquely alive, and preserved by their illicit desires and obscene thoughts.” Her work excavates the rotten core of the human condition, exemplifies the modernist preoccupation with capturing moral ambiguity.

As Constance Higgins writes in her Telegraph review: “To read I Am Alien to Life is to feel like you’re peering into the doll’s house of a particularly nasty child. Each story is a room; each room is filled with languishing figurines struck by some horrid twist of fate. Admittedly, to study this collection carefully is to notice that the child has a weakness for certain plots; this isn’t Barnes at her most various, and scenes, words and images recur…Assessed individually, though, each story manages to blaze. ‘It was all very sad and puzzling, and rather nice too,’ the narrator of ‘No Man’s Mare’ remarks of a rotting corpse. It’s a paradox that throbs throughout the book, and becomes its neatest summation too.”

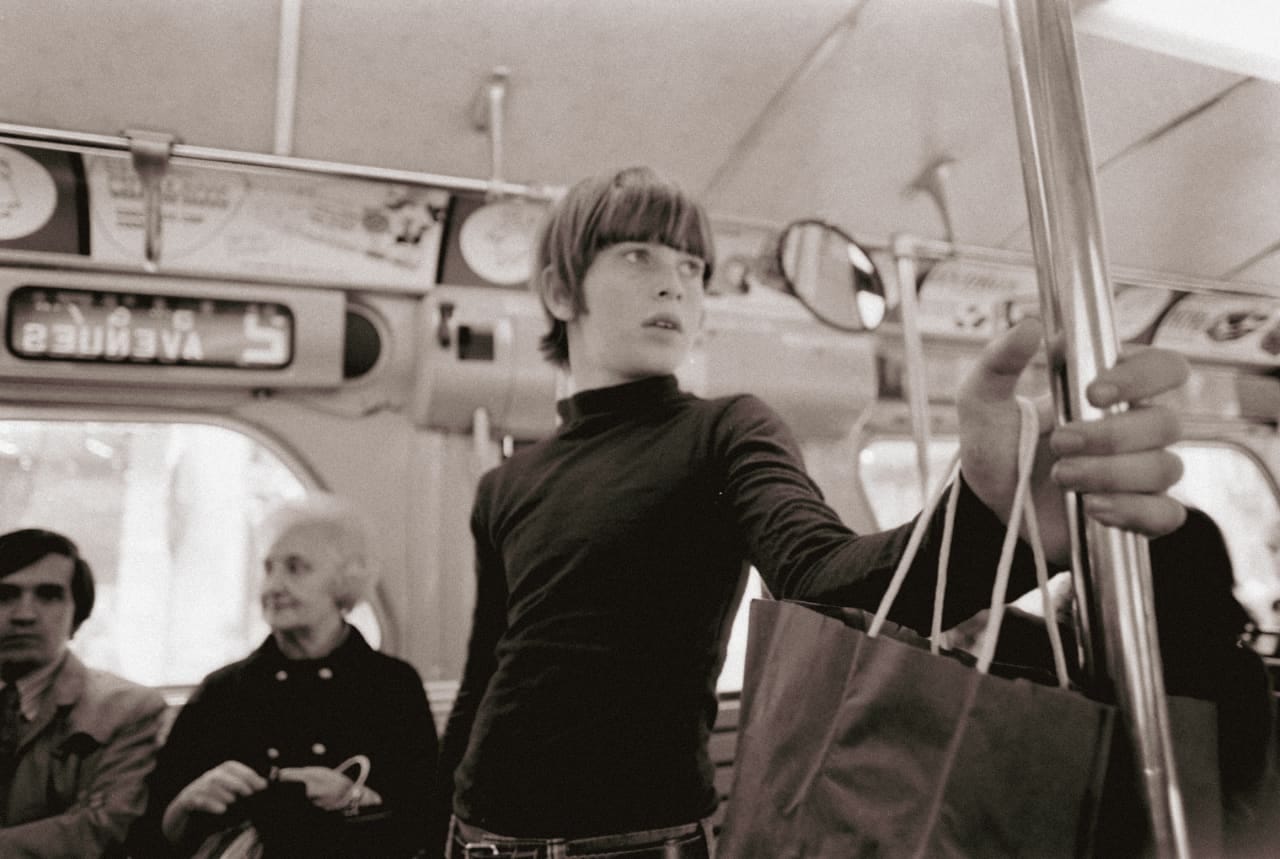

A Gorgeous Excitement by Cynthia Weiner (2025) — As a recent Chapin grad, Cynthia Weiner spent the summer of 1986 exploring the city by day, drinking at Dorrian’s Red Hand — the go-to bar for the uptown teen circuit — by night. One member of her broader circle? Robert Chambers, the cute guy who had gotten kicked out of a string of schools and, as a result, knew practically everyone. A kind of Dr. Jekyll, Chambers had the capacity to help a stoned-out-of-her-mind Weiner into a cab outside the American Museum of Natural History — and scream at her for tossing an unfinished joint out her parents’ window.

On August 26, 1986, the safe insulation of Weiner’s world cracked. News broke of a body found in the park — with a Dorrian’s matchbook in the pocket. 18-year-old Jennifer Levin had died at the hands of Chambers, a murder he tried to pass off as a mistake. The case became tabloid bait, with Chambers’s attorney using as many public forums as possible, including a New York Magazine cover story, to blame Levin for her own death. Weiner tells Air Mail: “The story always stayed with me…I pictured her in those moments before he strangled her…She was probably feeling really sexy. She was with this guy she’s got a big crush on, feeling free, and just those moments when he put his hands — what that must have been like…I related to her a lot, and that was one of the reasons it haunted me.”

A coming-of-age story a la Emma Cline’s The Girls (2016), A Gorgeous Excitement (2025) — which draws its name from Sigmund Freud’s description of the sensation spurred by cocaine — follows 18-year-old Nina Jacobs through the summer of 1986. Nina recently graduated from her all-girls private school and has one primary plan before leaving for Vanderbilt: losing her virginity to Gardner Reed. Nights at Flanagan’s — a fictionalized iteration of Dorrian’s — serve as the backdrop for her pursuit, a welcome counterbalance to the bore brought on by her daytime temp jobs. She toggles between her friendships with Leigh and Meredith, childhood relics and part of the Flanagan’s crew, and Stephanie, a Long Island born-and-bred newcomer with a coke habit, all while managing her mentally ill mother.

From its first pages, A Gorgeous Excitement introduces the brutality of its denouement. The novel opens with: “It was the summer of 1986 when the girl was found dead in Central Park behind the Metropolitan Museum — half-naked, legs splayed, arms flung over her head. Larynx crushed.” Weiner then goes on to infuse the book with violence subtle and overt, a sense of foreboding. For example, visiting a sex shop in Times Square, Nina and Stephanie meet a sadistic cashier who confronts them with a particularly violent porn magazine page. Weiner narrates: “Stephanie took off her shoes again, but Nina was too disheartened to police her…The absurdity of thinking she’d gotten even with the guy by swiping a couple of dumb plastic bracelets. He got the last word without saying a word: she was just a subhuman sex toy, a hanging carcass in the window of a butcher shop.”

The prose carries tinges of death and decay. For instance, Weiner describes a girl finishing “her (fourth? fifth?) Negroni in two quick gulps, her eyes already at half mast.” Taking a personality quiz with her friends at Flanagan’s, Nina gets asked to pick her favorite body of water and writes “‘bath,’ even though there was nothing viler than sitting in a swamp of your own dead skin.” She also wears “a new purple lipstick, Violet Kiss, which she initially misread as Violent Kiss when she tried it on at Saks.” As Johanna Berkman writes in her Air Mail review: “Weiner’s absorbing prose, combined with her detailed evocation of 1980s New York — the era of Area and the Quilted Giraffe, Tab, and SlimFast — will keep you reading and, if you’re of a certain generation, reminiscing.”

Weiner captures the contours of a bygone era, the dark mania that defined Manhattan during Reagan’s reign. Sharing her playlist for the novel with Largehearted Boy, Weiner explains: “Music in the 1980s was unabashedly over-the-top — synthesizers, hard-driving guitar riffs, propulsive drum fills — both mirroring and perhaps contributing to the manic energy of the time.” The novel’s pop cultural accouterments couple with the near-constant presence of coke, with a weeks-long manic episode from Nina’s mother, to create a mood of invincibility laced with fragility. Per Kirkus Reviews: “Weiner’s recreation of the period and the milieu — the headlines, the music, the products — is like a perfect pointillist painting, all the tiny details adding up to a richly textured, authentic impression of the city as it was in that decade…Carefully paced and beautifully written, this edgy coming-of-age novel succeeds on all counts.”

That’s all for now!

I will once again have a round-up of all the Best Picture nominations to you all in a few weeks as we get closer to Oscar Sunday. Stay tuned!

xo,

Najet