A Look Back: April Book Review

On The Anthropologists (2024), Good Girl (2025), and My Brilliant Friend (2011)

Lots of Europe-set fiction this month! I started out with Ayşegül Savaş’s The Anthropologists (2024) before devouring Aria Aber’s stunning, Berlin-set debut novel, Good Girl (2025), in a matter of days. Then, I spent the second half of April finally reading My Brilliant Friend (2011), the first of Elena Ferrante’s four Neapolitan Novels.

Let’s get into it:

The Anthropologists by Ayşegül Savaş (2024) — This lyrical novel from Turkish author Ayşegül Savaş adopts the first-person perspective of Asya, an expat living in an unspecified foreign city with her husband, Manu. Asya and Manu come from two different cultures, the specifics of their backgrounds abstracted. They form a shared life, a mutual language, on neutral ground, far away from their families. The narrative inhabits Asya and Manu’s bubble, drawing its meaning from minutiae. It traces the mundanity of their days, from drinking beer with their friend, Ravi, to reading poetry with their elderly upstairs neighbor, Tereza. Asya and Manu’s hunt for a to-purchase apartment occurs in the background, punctuating this particular phase as a waning one.

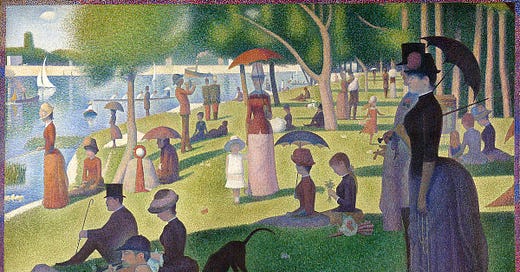

Savaş conceives of her chapters as rhythmic vignettes, coalescing to create the same kind of structure that shapes Sarah Manguso’s in Very Cold People (2022). In the chapters titled “In the Park,” Savaş breaks from Asya’s first-person point of view and instead inhabits the perspectives of locals. Throughout the narrative, Asya, a filmmaker, develops a documentary about their local green space; these sections remove her as an experiential mediator. Toward the end of The Anthropologists (2024), Asya’s interviews appear together, a constellation designed to capture a local color in a specialized shade.

In Savaş’s world, biological family witnesses your life through a keyhole, one predicated on a heightened construction (“She [Tereza] was even more animated than usual, with her daughter to witness the gathering.”). Asya and Manu witness visits between their beloved upstairs neighbor, Tereza, and her daughter. She views her mother, first and foremost, as an elderly woman, whereas Asya and Manu see Tereza’s artistic sensibility above all else. Meanwhile, Asya reflects on a visit from her father, stating: “Even after several visits, he didn’t really know how we lived: he had never been to the market where we shopped on weekends, the cafes we frequented, the tree-flanked square where we went to read on weekend mornings.”

Asya and Manu consider their home, a tiny rented apartment, less concrete than the structured relief of their families (“There was our life in the city and there were all our lives elsewhere, floating in and out of the present.”). For example, on Manu’s birthday, the couple spends the entire afternoon on calls with relatives, Asya wracked with guilt about the small scope of their day. But her preoccupation stems from perception as opposed to reality. She explains: “On Manu’s birthday, I woke up feeling sad that I was all he had for a celebration…Or rather, I felt it might appear that way from the vantage point of our families, who woke up on our birthdays and imagined us all alone in the city…The next day was more cheerful, without the worry that we were making our families sad on happy days.” Their life feels real, but an outsider’s view slackens its shape.

Notions of biological versus found family permeate the narrative. When chosen connections splinter, the fragility of youth gets laid bare. In turn, The Anthropologists emerges as a novel about recognizing and mourning transience.

Good Girl by Aria Aber (2025) — This debut novel from poet Aria Aber easily goes down as one of my favorite reads of 2025 so far. Set in the summer of 2010, Good Girl (2025) centers on Nila, an 19-year-old Afghan girl born and raised in Berlin to immigrant parents. At a bunker-turned-club, she meets Marlowe, an American novelist twenty years her senior (“I usually liked my men blond and severe or dark and tar, but Marlowe was neither, somewhere smack in the middle, with a square jaw and dimpled chin, the nose of an emperor…He was a prince who moved through rooms as if they belonged to him, surrounded by a large group of friends, among them his blond girlfriend, who in my memory always wore a Sonic Youth shirt.”). A fraught artistic and sexual connection emerges, catalyzing Nila’s public and private exploration of identity (“Marlowe and I had been ignoring each other — we danced through the cosmos of parties, but the moment he came too close to me, I would move in the opposite direction.”).

Raised in Germany by Afghan parents, Aber writes in English, her third language. She cites James Baldwin, Marguerite Duras, and Jean Rhys as influences, while praising the contemporary work of Raven Leilani and Garth Greenwell. Speaking with American author Kyle Dillon Hertz for Interview Magazine, Aber explains: “I really love her [Rhys’s] take on the stream of consciousness and the kind of deranged exilic woman stumbling through a city.” Good Girl operates as a 21st century enactment of that literary tradition, capturing the post-9/11 Arab and Persian experience through the particular prism of Berlin. Hertz praises Good Girl as a “poet’s novel,” a fitting description for a novel with language as its crown jewel. For instance, describing the connection Nila feels to Marlowe, Aber writes: “The eros…drew strings between us sometimes so taut they produced a sweet and secret sound. But the friction was frail — it was never meant to make real music, just to suggest its existence, like a violin encased in glass at a museum, so old and brittle it would fall apart if you tried to play it.”

Told from an intimate first-person point of view, Good Girl bears structural similarities to Adam Ross’s Playworld (2025) and Bret Easton Ellis’s The Shards (2023). All three novels trace a transformative year in the lives of their respective protagonists, recounted by an older iteration of that individual. Speaking at McNally Jackson Seaport in January, Ross compared this narrative framing to the experience of an aquarium visit. While the protagonist in the era of the primary action floats through life, their older self functions as a kind of tour kind by widening the aperture around particular moments. Good Girl thrives on immediacy, its character and setting synonymous with the present moment. But this narrative tool injects the novel with necessary moments of insight, contextualizing this year in the broader scope of Nila’s development as an individual and as a photographer (“I had the idiocy of the very inexperienced, which made me believe in my own greatness.”).

The option of ethnic ambiguity propels dramatic tension. Nila passes as Greek, as a whole host of backgrounds other than Afghan, to evade the discrimination that accompanies her real identity. The possibility of discovery drives her anxiety, its stakes heightened by the setting of Berlin — a city “particular and historical and shattering.” Discrimination in all its forms — from islamophobia to antisemitism — lurks, then creeps to the foreground. At one point, Nila attends an event that emerges as a fundraiser for Afghan dogs. She narrates: “‘Greece,’ I said. ‘My parents are Greek.’ The group started cooing like a bunch of birds, and I was happy they wouldn’t know my real heritage — they would’ve probably asked me to give a toast to these Afghan dogs…There was not a single immigrant in sight, not even the servers…I didn’t belong to the people in that [Qurbani] bakery, but I didn’t belong to these people either.” Alienation, the perpetual liminality that can fester in the children of immigrant parents, bubbles beneath her every experience.

In one scene, Nila sits in the front of a cab, while Marlowe zones out in the backseat with their friends. The driver reveals himself as Tigray and engages Nila in a conversation about the political history of Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Egypt. She longs to reveal how “the vivacious story of the Tigray guerrilla fighters resemble[s]…the myriad stories of Afghanistan and its freedom fighters,” but stays quiet. Marlowe goes on to scoff, “Cab drivers are always so damn depressing.” Nila narrates, “I felt terribly sad and alone, altogether much closer to the cab driver than I was to Marlowe.” This moment couples with the sequence at the fundraiser to distill the reality of what it means to pass as an ethnicity other than your own. Physical ambiguity coaxes people into revealing their prejudices, blinded by the illusion of unmixed company.

My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante (2011) — This oft-discussed book functions as the first of the Neapolitan Novels, a four-part series dedicated to exploring the friendship between Elena “Lenù” Greco and Raffaella “Lila” Cerullo, two girls growing up outside Naples in the aftermath of World War II. Told in the first person from Lenù’s point of view, My Brilliant Friend (2011) opens in 2011. Lila’s son, Rino, calls Lenù to inform her of — and ask for intel around — his mother’s sudden disappearance. The narrative then moves backward to the 1950s, with this first book tracing Lenù and Lila’s shared childhood and adolescence.

Yin and yang, Lenù and Lila exist in relation to each other. Tough and outspoken, Lila borders on abrasive (“More effectively than she [Lila] had as a child, she took the facts and in a natural way charged them with tension; she intensified reality as she reduced it to words, she injected it with energy.”). Meanwhile, Lenù has a porous identity. Her understanding of self emerges through opposition. The lens of others’ perception colors her as “good,” Lila as “bad,” a balance that brings internal order. On its own accord, personal experience becomes sapped of meaning (“I soon had to admit that what I did by myself couldn’t excite me, only what Lila touched became important.”). For example, Lenù finds success through academics over the course of the novel. When Lila’s interest in school wanes, Lenù struggles to maintain focus without an undercurrent of competition, reflecting a toxic texture of female friendship.

Elena Ferrante enlivens the people, places, and cultural customs that shape the girls’ neighborhood. In turn, it molds them, even as Lenù travels beyond the borders to school, to Ischia. Dramas small and large, from the disappearance of their favorite dolls to the murder of a feared neighbor, become the brushstrokes that color Lenù and Lila’s world. Tension stems from the socioeconomic dynamics shackling their community. Lila longs for upward mobility, a dream she makes manifest as a teenager, while Lenù, the better off of the two from the outset, dreams of intellectual impact. These divergent priorities reach a crescendo in the novel’s final pages as Lenù experiences the heartbreak, Lila the fear, of walking through the woods with a friend, then choosing opposite paths (“I was ashamed of myself, but I was no longer able to trace a coherent design in the division of our fates. The concreteness of that date made concrete the crossroads that would separate our lives.”)

That’s all for now! Stay tuned for the May newsletter.

xo,

Najet