A Look Back: April Book Review [2024]

Diane Oliver and more Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

If you know me IRL, you know it’s been a hectic month-ish, so thank you for bearing with me on the delayed April Book Review.

Let’s get into it:

Neighbors and Other Stories by Diane Oliver (2022) — Back in February, I flagged a then-upcoming talk at The Center for Fiction focused on the work of Diane Oliver, one of two Black students at Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the mid-1960s. As a refresher:

An avid reader, Diane Oliver grew up in the Jim Crow South before attending University of North Carolina at Greensboro, where she served as editor of the school paper. Upon her graduation in 1964, Oliver earned a slot in the coveted Mademoiselle Guest Editor program, which, from 1938 through 1980, extended summer internships to an extremely selective group of college-age women. The likes of Joan Didion and Sylvia Plath participated, with Plath’s experience famously fueling The Bell Jar’s narrative. (As an aside: I highly recommend The Barbizon: The Hotel That Set Women Free by Pauline Bren if you’re interested in learning more about the program and its legacy; Mademoiselle had a partnership with The Barbizon to house its Guest Editors.)

Oliver’s work went on to appear in The Red Clay Reader, The Sewanee Review, and Negro Digest, facilitating her entry into the nearly all-white environment of Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the 1960s. In a piece for Bitter Southerner, cultural critic and writer Michael A. Gonzales positions Oliver as a narrative predecessor to Jordan Peele. He writes: “Oliver’s naturalistic prose feels as creepy as Shirley Jackson’s in her infamous tale of a small town and its annual rite in ‘The Lottery.’ While Jackson’s story was fiction — yet still upset many readers — the Jim Crow racism depicted in Oliver’s stories was real. Her style is packed with complex ideas told simply, but never as simply as ‘protest fiction.’ As a student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in 1965, her writing goals were literary, not preachy agitprop. The people she wrote about dealt with hundreds of years of real-life traumas that included slavery, lynchings, beatings, harassment, and constant uncertainty.”

Oliver died in a motorcycle accident in 1966 at the age of 22, just weeks before her Iowa graduation. Per Gonzales: “Both Jet and Negro Digest published obituaries. Jet said the young writer had accepted an editorial position to begin upon graduation. Negro Digest called Oliver’s death ‘a premature climax to a short, but notable career in which it was our pleasure to publish some of the budding writer’s work…Along with her writing, Miss Oliver was involved in many campus activities including Civil Rights and Vietnam protest demonstrations. Her last summer was spent as a teacher’s aide in Operation Head Start…We were saddened by her death, but we choose to remember the warmth of her smile.’”

Oliver’s first and only short story collection, Neighbors and Other Stories, published in July of 2022.

In her introduction to Neighbors and Other Stories, An American Marriage author Tayari Jones astutely identifies the mood of the collection as “the feeling of sorting through a time capsule sealed and buried in the yard of a Southern African Methodist Episcopal church in the early 1960s.” The book consists of 14 short stories, published both during Oliver’s lifetime and posthumously. Each one grapples with the intimate reality of integration, recognizing the personal and political as one and the same.

Through her body of work, Oliver provides a glimpse into the emotional life of Black Americans at a heightened moment of social upheaval. She delves into the psyches of Black people ranging from a depressed college student experiencing racial isolation (“To decorate her room, Winifred had moved in with a whole zoo. Aside from the dog, there was a small tiger with leopard spots guarding the dresses, a yellow bunny three feet high named Mandy, a green duck, and a fuzzy lamb. The animals were the first things she looked for when she woke up in the morning.”) to a mother battling a doctor’s office wait with her children in tow (“If the nurse didn’t call for them soon, she knew they’d have to go home. She hadn’t thought to bring anything for a lunch and they couldn’t afford to buy anything out of the cracker machine.”) to a woman fending off unwanted questions from her nosy employer (“‘Did you take Wicker back to the doctor?’…It seemed to Libby that if Mrs. Nelson were so concerned about Wicker she would suggest bringing all the children to play in her backyard during the day. That way Libby could keep an eye on them herself.”).

In the titular story, “Neighbors,” a family prepares to send their son, Tommy, to a newly integrated school the next morning. Oliver drops into the anxieties of Tommy’s older sister, Ellie, writing: “She tried to put him to bed again but he would not go, even when she promised to stay with him for the rest of the night. And so she sat in the kitchen rocking the little boy back and forth on her lap.” In her introduction, Jones observes: “The title story…stands in stark contrast to the iconic image of six-year-old Ruby Bridges, precious in braids and a pinafore, bravely integrating her elementary school…Despite the triumph of Brown v. Board of Education, is it morally right to send a child where, at best, he is not wanted?…Is there a true distinction between what is best for the race and what is best for their little boy? Whatever decision they make, there is no way that the reader can judge them because Oliver has taken us for an uphill walk in their shoes.” Neighbors and Other Stories, as a whole, operates as just that — “an uphill walk” in the shoes of Oliver’s characters, a cast grappling with the breach between the political as a collective ideal versus an individual reality.

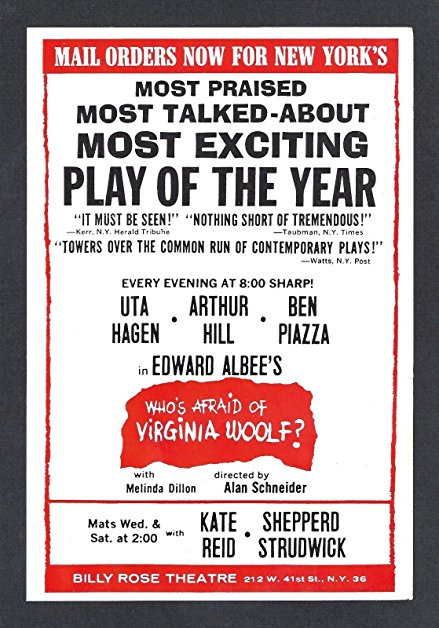

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? by Edward Albee (1962) — I had to round out my Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? era by reading the play as well. First things first, Edward Albee had every right to be pissed about Ernest Lehman’s screenwriting credit for the 1966 film adaptation; the scripts appear more or less identical, save for a few lines that Albee justifiably cast off as paltry additions.

ICYMI, as director Mike Nichols summarized, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? “is about a couple [George and Martha] who comes home late after a party. She has invited another couple [Nick and Honey] over for a nightcap. They drink and they argue and then the guests go home.” Throughout Cocktails with George and Martha, author Philip Gefter repeatedly characterizes the play as representative of marriage, both specifically and generally. As I described in my March review of Gefter’s book: “Over the course of an extended nightcap from hell, George, Martha, and their younger counterparts toe the line between truth and illusion, cracking open the cores of their respective relationships.”

Albee’s text leverages humor to toe the line between care and cruelty (“Why Martha! Your Sunday chapel dress!”), distilling the kind of dialect that come to comprise any long-term partnership. To me, the couples’ reversal of power marks one of the narrative arc’s most compelling aspects. Toward the start of the play, Nick and Honey project a greater sense of stability, of partnership, compared to their older hosts; they appear pleasant, seem supportive of one another. But a vacuousness belies their pleasantries and, as the night wears on, the social illusion they represent begins to crumble. Meanwhile, the barbs thrown between George and Martha emerge as a form of intimacy, come to constitute a kind of love language.

Stay tuned for the May Book Review and May Movie Review!

xo,

Najet